by Sherry Chapman

First published in April/May, 2005, Volume 2, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

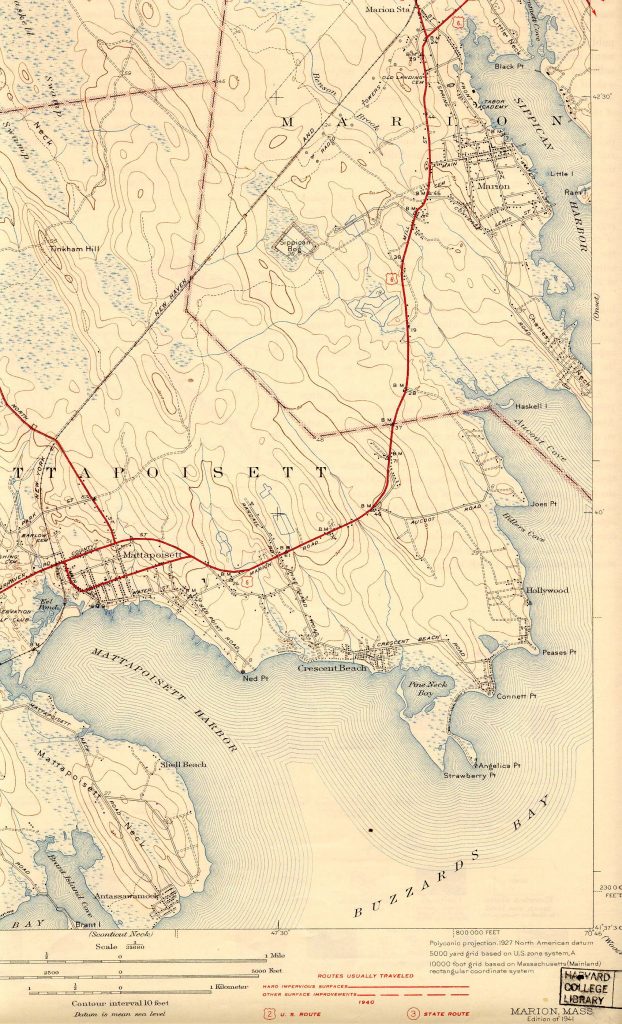

Last spring I was lucky enough to have a chance to visit the town of Marion. You know, the place where Lizzie was going to fish on Monday except the murder of her father and stepmother on the prior Thursday altered those plans. I wanted to see the town that Lizzie saw, see the waters of Buzzards Bay, walk down the same streets as she. Was it still a resort town? Was it still peaceful and pretty, like the refuge at which people back then vacationed?

The day I chose to go was a glorious summer-like day in April. The town was quiet, almost as if I was no longer in the day of the automobile, but somehow transported back to a time before hustle and bustle became two frequently used words in our vocabulary. The homes that were not quite fabulous at least were charming. People that I talked to made me feel as if they knew me all their lives. There was something special about the town; I could feel it. It was history. That sense of history in Marion is obviously a priority that either takes a tremendous amount of effort to maintain or else it comes easily—it’s hard to tell. It’s so natural, you step into it like a painting in The Night Gallery, only Marion isn’t scary. It is beautiful.

The day I chose to go was a glorious summer-like day in April. The town was quiet, almost as if I was no longer in the day of the automobile, but somehow transported back to a time before hustle and bustle became two frequently used words in our vocabulary. The homes that were not quite fabulous at least were charming. People that I talked to made me feel as if they knew me all their lives. There was something special about the town; I could feel it. It was history. That sense of history in Marion is obviously a priority that either takes a tremendous amount of effort to maintain or else it comes easily—it’s hard to tell. It’s so natural, you step into it like a painting in The Night Gallery, only Marion isn’t scary. It is beautiful.

I knew I was only there for the day (darn it). And I knew I could never learn the things I wanted to know about Marion in that short amount of time. The historical museum and its gift shop were as appreciated by me as the spending spree I did there probably was by the town.

When I got home, I read about this town that I never would have heard of had it not been for Lizzie’s story of looking for her sinkers in the barn for her trip to Marion. I should have heard about it because of all the little historical golden nuggets the town possessed. I hope that you are as pleasantly surprised as I was to find out that:

Marion was not named after some girl. It takes its name from a Revolutionary War hero, General Francis Marion. Nobody seems to know why he was chosen for this honor, but it is said that “Marion” was more easily understood when hailed from ship to ship at sea. At least, they are telling me as best they know [1].

Marion’s generous benefactress, Mrs. Elizabeth Tabor, contributed many private and public dwellings from 1874 until her death at the age of 96 in 1888. Her contributions include the Town House, the Music Hall, the Congregational Church Chapel and many others. She gave the town a lot of huge elms that line the streets, some of which were ripped up in the hurricane of 1938 [2].

Marion is home to Tabor Academy, also given by Mrs. Tabor. Tabor Academy, now 129 years old, provided free secondary education to children in town, and was the first institution of higher learning in southeastern Massachusetts. Since 1876, the school has grown with the town, and the education at Tabor compares with that of the best prep schools in the country. Tabor began as a co-educational facility. Today it is a boys’ school [3].

Many internationally known figures visited Marion in the last half of the 19th century, giving it the mix of worldly and local atmosphere that exists there today. With train travel, the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad made it possible for people from Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Washington DC to reach Marion in relative comfort [4].

The influx of famous personalities to come to Marion began with Richard Watson Gilder, the editor of Century Magazine, who was urged by a friend to come to Marion and take a break from his work in New York City. He bought an old stone building that had been used to store salt at one time and turned it into a studio for his wife, Helena deKay Gilder, an artist. Stanford White designed a fireplace in the “Old Stone Studio” which still exists. The address today is 46 Spring Street. In this unique setting, the Gilders played host to many friends, some of whom included: Charles Dana Gibson (the creator of the “Gibson Girl”), Augustus St. Gaudens (sculptor), Ethel and John Barrymore, Maude Adams, Evelyn Nesbitt, John Drew, Louis Agassix, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Frank Stockton (author), John C. Nicholay and John Hay (Lincoln biographers) and a popular actor of the time, Joe Jefferson, who was famous for playing Rip Van Winkle [5].

It was Gilder who first invited President Grover Cleveland and his family to Marion. Gilder had helped Cleveland to get elected. A steady fishing companion of the President was Joe Jefferson (see above). The Clevelands enjoyed Marion so much they named a daughter “Marion.” [6].

The author, Henry James, was another friend of Gilder and visited Marion. He wrote The Bostonians in 1886 and brought his main character to Marion, which he changed to “Marmion.” [7].

The most famous war correspondent at the turn of the century was Richard Harding Davis. He married an artist, Cecil Clark, in Marion in 1899 and reporters descended upon Marion to cover the wedding, which became front-page news across the country [8].

Other celebrities who visited Marion during the Gilded Age included artists Ellen Emmett Rand, John Singer Sargent, composer Walter Damrosch and Adolphus Greeley (explorer) [9].

The house at 300 Converse Road was built by Henry Vose Blankinship / Blankenship, who as a Fall River Policeman had been on duty the day of the Lizzie Borden murders. After the trial he moved to Marion [10].

The ship Mary Celeste left the wharf at Marion, to mysteriously disappear for many years [11].

Hosea Knowlton, the prosecuting attorney at Lizzie Borden’s trial, summered in Marion [12].

Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s right hand man was Louis Howe. Louis Howe was the husband of Grace Hartley Howe of Fall River, a close cousin of Lizzie Borden’s. President Roosevelt stayed at 9 Main Street in Marion during his frequent visits to Dr. William McDonald of 99 Water Street, his friend who treated his polio. Admiral Byrd is known to have summered here also [13].

21 Main Street: The oldest dwelling in Marion, dating to the 1690s [14].

George P. Hamlin built One Water Street in the early 1890s. His brother, Edward Hamlin, who built a home at 23 Water Street, was a cousin of Abraham Lincoln’s first vice-president, Hannibal Hamlin of Bangor, Maine [15].

One Allen Street was the home of Episcopal minister John Brooks. His brother, Reverend Phillips Brooks was a frequent visitor, who was known for writing the Christmas carol “O Little Town of Bethlehem” [16].

The Sippican Hotel was occupied by many of Marion’s summertime visitors. It no longer stands. Today the site is at 88 Water Street. When Henry James wrote The Bostonians (1886) he made reference to the hotel as “a shabby and depressing hostelry that suggested an early bed time.” The hotel was torn down in the 1920s [17].

173 Front Street: The cellar hid runaway slaves [18].

Modern-day celebrity Geraldo Rivera lives in Marion. Though a resident I stopped to talk with gave me directions to his home (he was mad – it was right after Geraldo slipped up and gave the world the then-unknown location of our troops) I’ll respect Mr. Rivera’s privacy and not put it in print. Some locations really should be kept secret.

Endnotes:

1 – 8: Sippican 76, Official Publication of the Marion Bicentennial Commission, 1976.

9: The Magic of Marion, The Sippican Historical & Preservation Society, Summer 2003.

10, 11: Marion Memories, Volume 1, “Interviews with the Locals,” Sippican Historical Society, East Freetown, Massachusetts, 2001.

12 -18: Rosbe, Judith Westland. Marion: Images of America. Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, SC, 2000.