by Eugene Hosey

First published in October/November, 2005, Volume 2, Issue 5, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

The Fall River Historical Society

The drive from Providence to the Fall River Historical Society is a smooth, error-free trip. After looking at several confusing maps, I had the foresight to get directions from a Fall River native. When Rock Street crosses French, I resist the urge to turn and look for Maplecroft. The FRHS appears to my left just a few streets over. The building is a square of solid gray stone and would have a mausoleum-like austerity if not counter-balanced by some colorful wood trim. A small portico with two round columns covers the Rock Street entrance. The double doors are locked. I ring the bell, and an attractive lady opens it with a smile. “I expect to meet a group of people here,” I say, realizing this is an odd way of introducing myself. But she seems to understand. “They’re here,” she says, and ushers me inside the hall, where she opens another door. This is a somber, lofty room; deep in historical ambiance, furnished with antique wood and precious decor. In this close, reverential space, I meet the flesh and blood of my Borden Case friends who have heretofore been entities of electronic media. We share immediate recognition, and I even have the pleasure to hug a few.

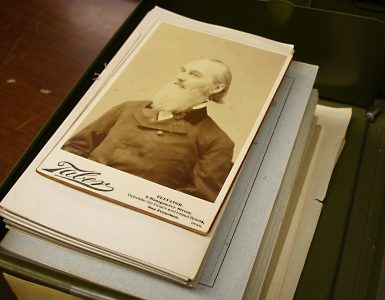

Within a few minutes of my arrival, the guide announces it is time to view the Lizzie Borden exhibit, which is in a room directly across the hall. Two horizontal glass cases, pushed together, occupy the center of the room. One case contains primarily the Borden family photographs, while the other reveals the crime evidence. Here is the folded bedspread and pillow sham from the guest room, both showing a few brown spots. Abby’s braided hair extension is long like a pony tail, some of the hairs at the severed end still matted from the blood. We are told that here are two tiny vials of the victims’ blood, now dried and solid. Several of us pore over the photograph of Abby with the bed removed. This is fascinating, as the superior resolution of the print reveals what seems to be a huge quantity of blood that is thick with a rubbery or glue-like consistency. In a third display against a wall is the handleless hatchet, which is smaller than most hatchet blades I’ve seen. Harry and I agree this is not the culprit. And here are the hair samples: Abby’s predictably grey, Andrew’s surprisingly blond.

Our tour guide is a senior Fall River native. Before giving her standard narrative, she shares her personal perspective on Lizzie. In the old days, nobody ever talked about Lizzie Borden; now there is a worldwide obsession, she says in a voice resigned to exasperation that the case dominates her town’s history. Her account of the murders is routine enough except for the notion that Abby was struck while holding the pillow cases she intended for the bed. This could as easily be true as false – another “source” question.

The weather today is certainly appropriate if it was as hot as they claimed it was 113 years ago. Someone wisely suggests we visit the cool archives downstairs. This level is fairly stuffed with filing cabinets, shelves, books, and every form of print media. There is a reading area with a large table at one end of the space; in fact, a researcher is busy there now. The other direction gives way to small offices. I recognize Michael Martins from the Borden documentaries. He is in conversation with someone at first but later, as he appears to be on his way out, Kat asks him about the handkerchief featured in last October’s Discovery Channel special. It was demonstrated that the handleless hatchet did fit cut marks in the handkerchief. He confirms that the historical society is in possession of it, although it is not on display. I notice what is obviously the Borden bookcase. I select a book on murder and astrology and look up Lizzie’s birth chart and jot down some particulars; this astrologer gives her a Virgo rising sign; interesting, Andrew was a Virgo. Some Forum members are leaving for food or rest. After I am outside the building with Stefani, Kat and Harry, the decision is made that I’ll leave my car and join them for a visit to the B&B with a stop at Maplecroft on the way.

Maplecroft

Seeing Maplecroft in the context of some of the Victorian houses on Rock Street that are four times its size, Lizzie’s inheritance prize seems rather modest. The house has been painted since the last photographs I saw were taken. Otherwise, there is nothing unfamiliar in any view from the sidewalk. Several windows are open, curtains fluttering in the breeze, but there are no sounds from the house.

We manage to get close enough to observe some interesting details on the left side of the property, where Lizzie’s spiked iron fence still stands. The sun room extends about halfway around the house and stops strangely; where one would expect it to simply attach to the house, there is a door so narrow it is hardly practical, with steps of the same width to the ground. I would guess the original porch jutted out two or three feet from the outside wall of the house, and that vertical slither of space is an inevitability of that. But I wonder if it was used ordinarily as a door, or if it had a more eccentric purpose. I have noticed disagreements as to whether Lizzie and Emma had bars installed on the cellar windows, but they are clearly visible here, on this side of the house, anyway.

92 Second Street

I’m in the middle of saying something to someone in the car, when an extreme close-up of Andrew Borden’s house on Second Street unexpectedly flashes by in the car door window. Stefani parks on the block south of Spring Street. I get out of the car and consider The House in the context of its surroundings. It is a living anachronism stranded in sun-baked urban concrete, with a fresh coat of two-toned green. I see how close Andrew was to home when he stopped at the new store on Main. I could close the distance in two minutes.

I’m aware that photography never prepares one for interaction with a real physical space. I think it has to do with the way film flattens an image and stimulates the imagination. A photograph conveys a mysterious impression of what is simple space in the three-dimensional world. There are only six paces from the front door to the door of the sitting room. From a west-wall seat in the parlor, the greater part of the sitting room is apparent. If all downstairs doors are open, you can stand in the parlor doorway, facing east, and by simply stepping to the left or right of the doorway, you can see into every downstairs room. I say this to illustrate how the space is instantly demystified by the experience of physical contact. In my imagination, these rooms have been surrounded by total darkness, and buried in the depravity of the crimes.

Presently, the house seems utterly friendly, the carpets and wallpaper warm and charming. We sit in the parlor as the tour guide, Ben, starts his narrative. Lizzie Borden took piano lessons, he says, indicating the piano on the south wall of the room. These interior doors were used by the Bordens themselves, as he puts it.

My eyes have fixed on the The Sofa just inside the door to the sitting room. It sits there innocuously enough, indifferent to my prying eyes. Something about it bugs me. When we move from the parlor to the dining room, I realize that I do get a bad impression – not from just the black sofa – but from the sitting room in general, or that general part of the house. It is an unfamiliar, unanticipated vibe.

But for now, I join the others in the dining room. There is a framed collection of Trial sketches from one of the Boston papers. Harry and I look this over and agree that one or two rare images are displayed. There is one I know I have never seen; it shows Emma’s features in some detail, and I detect a resemblance to Lizzie.

I am still curious about my impression of the sitting room. I stand at the sofa where the killer probably stood and consider it. Is it the odd way that three doors converge in this corner, while the sofa is in the direct path of all three, that makes it seem wrong? Or is it simply the dominant black in the room’s décor? There is no ghostly appearance, cold spot, or anything that seems supernatural. But it has a stifling grimness or ugliness. Perhaps the impression would fade were I to stay in the house for a prolonged period of time.

Ben continues the tour in here at the head of the sofa. As I scan the shelf contents in the corner, I hear him describing Lizzie’s discovery of Andrew’s body, her call to Bridget, and her talk with Mrs. Churchill. For the second time, I hear that Lizzie made small talk with Mrs. Churchill about the heat before mentioning the murder. I recently ran across it in the Engstrom book. Perhaps there is a single, probable source, even if apocryphal.

The tour proceeds up the front stairs ahead of me, while I pause in the foyer. A look at the front door reminds me of a circumstance so inconsequential I almost forgot it. A few minutes ago, the front door opened on its own. A car whisked by just outside the opening. Someone stepped over and closed it securely. The front door did not shut reliably in the Bordens’ day either, according to both Morse and Lizzie.

The stairway is well-preserved, its curve at the top a beautiful feature whether looking up or down the stairs. I count the steps until I’m eye-level with the second floor. I say, aloud, “Seven.” This evokes a laugh from the folks who are now in the guest room. Ben is standing between the bed and dresser; he drops to assume dead Abby’s position for my camera. Interestingly, I can see his form with the naked eye, but it does not register in the digital photograph. I wonder how the height of this bed compares to the original.

Kat seems to appear out of nowhere and opens the door to what was Lizzie’s and Emma’s dress closet, where Victorian Lincoln imagined a bloody dress hidden underneath another. It is a large, immaculate bathroom, distinctly rectangular and roomy for a closet. The guest room, literally the size of the parlor, is significantly more spacious in reality than it has been in my imagination — probably because the western half of the room does not appear in the crime-scene images. I stand at the window near the murder and try to imagine the side of the Churchill house, which has been replaced by a view of leaves. Was Abby contemplating something or just gazing out the window, daydreaming, before she heard someone behind her and turned? Had she heard or seen something disturbing, or had she merely paused from her housework? The dresser and bed are remarkably accurate to 1892, but there is no sinking dread in my stomach or ghostly presence. I sense nothing unusual at this crime scene, unlike the one downstairs.

A headless mannequin in Emma’s room wears a dress belonging to Lizzie. Kat points out how surprisingly petite it is. Indeed, the mannequin is tiny, and the dress is tightly stretched. The material does not feel refined, but almost coarse. How could Lizzie Borden be so small? Perhaps the material was shrunken from washing and age, and this is why Lizzie discarded it. I am remembering what Emma said about the condition of Lizzie’s Bedford Cord.

We enter Abby and Andrew’s room from Lizzie’s room. This strikes me as odd, at first, because in my mind this door is a forbidden entry; but, of course, it would be silly to go back downstairs just to go in there, wouldn’t it? There is something unusual in the elder Bordens’ closet — a little inner door that accesses space around the chimney. It is also interesting that it is not clearly mentioned in the trial documents. Here is fair game for a theory, I think. Then Kat demonstrates that this closet door — either reliably haunted or off center — will not stay open.

The attic has three rooms outfitted for guests. A bathroom has been installed where Morse used to sometimes sleep. The Bridget room is in the southeast corner. There are two large rectangular rooms on the west end toward the street. I don’t explore far up here, though, because there are two or three occupants. I catch sight of an irritated glance. I have always wondered how the overnight guests contend with the tours.

Kat and I go downstairs, past the second floor to the first. I want a look at the screen door and the back entry. I know I’m not the first to think, “Mrs. Churchill, do come over.” Kat clarifies something in the kitchen/entry area that has confused me. What is now a bathroom behind a solid wall in the entry is where the sink room and pantry were located, in two small rooms, side by side. Our voices here are interfering with the tour, so we go down cellar.

The underground level is all concrete, stone, brick; and strange discolorations in the old, naked walls. The area directly underneath the kitchen is where the bucket of bloody rags and the victims’ clothes were left overnight, and where Officer Hyde observed Lizzie return that night alone. There are several stone walls extending about halfway across, making alcoves. There is an area for Lizzie merchandise, and also some office space. Kat and I discuss the luminol-testing demonstrated in Lizzie Borden Had an Axe while looking up at the wood beneath Andrew’s murder site. Apparently, some people believe the floorboards of the sitting room were turned over after the murders. To speak of the long arm of coincidence — Lee-Ann tells us that when she changed the guest room carpet, she discovered that the floor where Abby was murdered has obviously been bleached. Then she asks us to look at something in what seems to be a storage area. These are the artifacts from the backyard excavation. I think I’m surprised at the amount of it. A lot of large nails and tool fragments; I notice nothing axe-like. Several small glass vials for liquid medicine, unchipped and still vividly blue; a white ceramic lid to a bowl or chamber pot; a partially reassembled plate with a blue, vine-and-leaf design. The oddest thing is the remnant of a shoe. Perhaps some of these items can eventually be dated or specifically identified.

At this point, I’m aware that Stefani is anxious to leave to prepare for her talk. The four of us, Stefani and Kat, Harry and I, pause in the sitting room. I don’t have the same discomfort here I did before. Unlike the other windows, the windows in the sitting room are said to be original. This is understandable since the print shop has closed them off for so long. These windows are certainly old; it is evident in the glass (a kind of faint blur) and the structure; there is a little lever, apparently for securing something external such as storm windows, screens, or shutters. Harry and I both take some obligatory “seated on murder sofa” photographs. I would hate to nap on this sofa, which was not made for comfort.

As we leave, Lee-Ann shows us the little glass panes behind the narrow shutters that flank the front door. I never knew they were there. Kat hands me a pear she got underneath the little pear tree growing in front of the parlor windows. To her dismay, I wipe it off and bite into it. I chew enough to get the flavor — it is pear, all right — and then spit it out. Only later do I realize the organic intimations of what was merely an instinctive reaction to a piece of fruit. I have tasted a pear grown on Borden property.

The Lecture, First Congregational Church

Stefani parks at a side entrance which is like an alleyway and hurries to prepare for her lecture. Doug Parkhurst is already there and offers us some sugar cookies baked by his wife. The Durfee High School (attended by three of the authors, Kat has reminded) towers over us on the hill. It is hard for me to imagine attending high school in such an imposing structure. What has impressed me about Fall River in general is its essential connection to an industrious past, evident in both public buildings and solid blocks of huge, time-weathered houses.

Every church has a fellowship hall, I suppose, for entertainment, eating, and a host of events that defy categorization. Fall River has Lizzie Borden. Stefani will begin her lecture by posing the question, “Where is Lizzie now?” She is referring, of course, to the clock 113 years ago, but someone offers an answer along a different line: “In hell?” This is apt enough to the legend, and I wish I had thought of it. But before this, there is a little time for socializing.

I hear some beautiful piano playing. Someone tells me the musician is something of a mystery but regularly plays at functions here now. Sherry Chapman and I discuss writing for The Hatchet. She has a wonderful laugh as I remind her of some of her greatest satires. Kash from the Forum unexpectedly arrives; we’ve never met but have a mutual friend. Mark Amarantes, Harry, and I talk about real estate values.

By the time I take a seat, the hall is filling up rapidly, with several people standing in the back. I recognize Rebello and Pavao. Lee-Ann enters, still in her green period dress. After an introduction and welcome, Stefani gets started. A Tina Rouse cartoon of Lizzie under a magnifying glass appears on the screen as an intro to the presentation. I did not plan to take notes, but I think I will, using the back of one of my confusing Fall River maps. Within five minutes, I can see that Stefani is totally professional, well-prepared and organized. And she knows how to work the adrenaline, staying confident, expressive, and conversational.

Her material is not tedious, but it has substance. As regards documentaries in general, I learn a new term, “The Ken Burns Effect.” The Borden documentaries encompass the genres of history, mystery, and the supernatural. Stefani demonstrates the “mixed-bag” character that is common to them all, in that historical facts tend to get blurred with apocryphal anecdotes. Outright misinformation is not uncommon. Attempts to solve the mystery can reveal a rare artifact or a thought-provoking possibility; but on the downside, these programs tend to be marred by confusing dramatizations; interesting experiments are ultimately pointless and fall into a “gee-whiz” category. The supernatural investigations may include credible witnesses, but they cater to a particular cultural phenomenon. For me, the most enlightening segment of the lecture is Stefani’s account of what she learned first-hand as a contributor to a particular program. It alleviates some bafflement on my part as to what governs the final product. The documentaries reflect the modus operandi of the entertainment industry. A producer will gather material from extensive sources, and then search this data for a script that meets the television industry’s entertainment criteria. The Borden scholar can readily see how this method can result in some real oddities. So are the Borden documentaries successful by any unqualified definition? They do serve to create general interest in the case. I would like to think that talented writers and filmmakers will find inspiration. Film effectively preserves images of things which may later disappear – from crime-related objects to the faces and voices of a legacy of historians and case experts.

Stefani’s star shines brightly tonight, and I feel very proud of her. Her presentation is an irrefutable hit. Almost everyone is anxious to talk to her. When I finally reach her, I ask if she would like for me to write up the event; she leaves that to my judgment, she says; but, of course, I cannot resist documenting the lecture along with the whole Fall River visit. I cannot remember when I’ve had such a fascinating day. If Stefani does this again next year, I’ll return for it. At any rate, every Borden enthusiast should make the trip for the Fall River Historical Society and the Second Street B&B, if nothing else. Ultimately, it is as essential as reading the trial transcripts. There is no substitute for laying eyes on actual physical evidence and occupying the actual space of the crime.

Time for me to head back to Providence, I decide. My rental is still at the FRHS. Someone who is returning there anyway offers me a lift. Unwisely, I decline and start walking. The street is dark and deserted. The wind is blowing eerily in the trees, and the Durfee High School seems like a gargantuan tomb as I walk past it. It dawns on me suddenly that I am somewhat spooked. I have gone in the wrong direction, and my imagination has fixed on morbid thoughts of this night in 1892. Lizzie Borden is walking home from Alice Russell’s about now, and an unspeakable discussion is occurring in that terrible sitting room where the black sofa awaits a brutal murder. And the murderer is lurking.