by Michael Brimbau

First published in Spring, 2011, Volume 7, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

THE WILD, WILD EAST

It was an airless, sweltering afternoon.

As he walked along the empty streets, the white sun throbbed in a cerulean, crystal sky. His mouth was parched and his nose tingled as he gazed up to the empty heavens for relief from the oppressive heat. He sported twin Colt 45 Peacemakers low above his scrawny hips. At times, he was obliged to give them a tug, lift them, lest they pull down his ill-fitting trousers. Taut black leather holsters, long and supple, were laced with rawhide just above his bony knees—his shoes untied. When he walked, his pistols swayed from side to side in profound obedience to a slow and steady swagger.

Though the day was sultry, there was enough of a breeze to blow back his navy blazer, exposing the impressive silver rivets that framed a shimmering gun belt. He wore a red silk ribbon tie fastened loosely around his slender neck, adoringly placed there by his mother. Like a flat, limp shoelace, it dripped low down his baggy white shirt in a splatter of unexpected color. A western straw hat sloped low on the back of his head and was held tightly by a twisted red and white plastic strap, just above his chin, bunching up his lower lip.

Wherever the bad guys were holed up, they couldn’t hide much longer from this steely, determined lawman. A gleaming, pointy badge with the word Sheriff, pinned proudly to his lapel, announced as much. Wyatt Earp was in town and justice was coming. But this was not Front Street in Dodge City, nor was it 1861. Virgil and Morgan were nowhere in sight—tumbleweeds were not silently whirling down a parched, dusty dirt road. Doc Holiday would not come stumbling out of Short’s Saloon to be his huckleberry. Instead, this was 1961 Fall River, Massachusetts—Quequechan Street—a loathsome thoroughfare, lined with tumbledown pre-vinyl tenement houses in their dotage years. Quequechan Street ran through a drained, spent, and herniated mill town, running south and north from the Pleasant Street Saloon.

Suddenly, and without warning, our hero was stopped dead and silent in his tracks. His slender arms, once bravely cocked with hands hovering over his toy gun grips, now lay trembling by his side. His quivering shoulders melted into his chest, and he squinted with fearful uncertainty. He knew it was too late to run away, that the bullets neatly wedged along his belt were only white hollow plastic—the pistols loaded with harmless red paper caps. He swallowed fear hard, trying not to display certain dread as three young ruffians, each at least a foot taller than he was, approached and surrounded him just outside Pelchat’s General Store.

Now, I don’t remember the exact circumstances, or detailed outcome—it was so long ago. But, I do recall it was not a happy one. I was proudly dressed as Wyatt Earp. As some may recall, The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, staring Hugh O’Brian, was a TV series that ran between 1955 and 1961. It was every boy’s desire to be a cowboy, to be old Wyatt. Unfortunately, the three bullies, more than likely, never watched an episode. They knocked me to the hard cement sidewalk, bloodying my shirt. (Though, I had a propensity for nose bleeds as a child.) Standing over me in bumptious victory, their silhouettes provided the only shadow I remember that frightful afternoon.

When it was all over, they casually swanked up Quequechan Street—never looking back (or perhaps it was I who did not look back at them), leaving our lionhearted, cow-lad gasping and weeping—holsters empty, guns missing, his little man courage tarnished. Such was life at times for a young boy playing in 1960s Fall River.

Sadly, growing up in the inner city, my memories of childhood are laced with many such despairing occurrences. Making new friends was always an arduous adventure and scouting out streets in search of someone to play with was a lesson in the practice of vigilance. Unknown territory was best avoided. Most of the time I remember playing alone—drawing up treasure maps, playing pirate, or laying on my belly while picking at ants with gooey popsicle sticks from crevasses in the sidewalk outside the house. My playground was usually limited to my back or front yard, where friends were easily made with a butterfly or a praying mantis captured in a jar—one with holes in its lid, of course. I rarely ambled further than one or two blocks from our front door. Anything farther was terra incognita, bully land. Wandering far from home, one had to practice a keen sense of timing to be back before the streetlights were turned on, to avoid the strap.

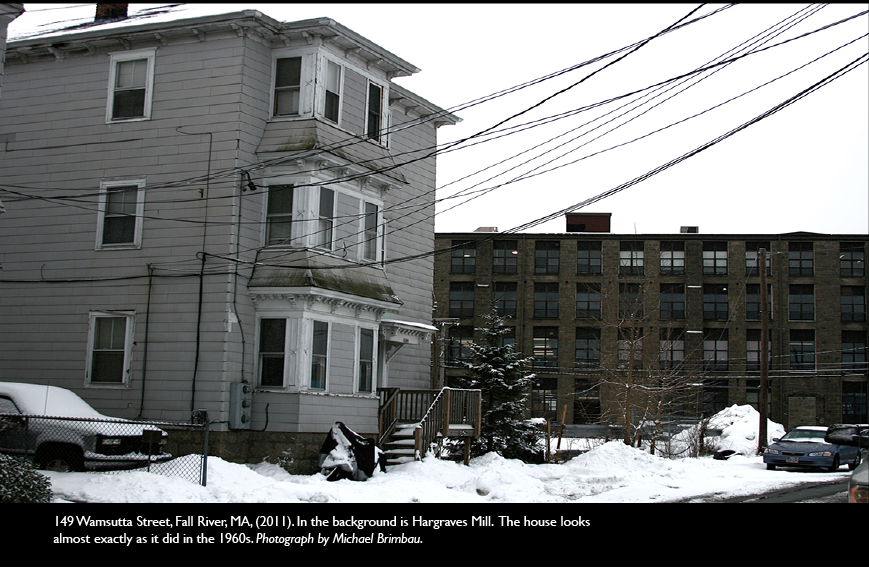

At the time of my little cowboy adventure, we kept residence on Wamsutta Street; a block away was Pleasant Street. The South and North Ends had Main Street—the East End had Pleasant Street. It was the life artery of the East End, better known as the Flint Section, in this, Lizzie Borden’s aging hometown.

As a family, we were always changing residences. It almost appeared as if we were continuously being rudely asked to vacate the premises. An eager landlord, who desired the apartment for a relative, may have dictated eviction. Other times, it was because the rent had become too dear. On a few occasions, Father obtained a job that was too far to travel to on a daily basis, and we had to move once again, north, to places like Lowell, Chelsea, and Bellerica. But, we always returned to Fall River. In my first ten years of life, we had moved to eight separate apartments, five of them no more than a half mile from my birth address on Canonicus Street. Such constant moving cannot be healthy for a child.

The choice to remain and live in the Flint Village in Fall River was an ecclesiastic one, more so than any other rationale. A religious parish was an institution working families joined for life. The congregation one belonged to designated the neighborhood one lived in. One would often hear someone mention, “Oh, he lives up by Sacred Heart,” or “She works down by Holy Name.” We belonged to the Espirito Santo Parish, a small Portuguese Catholic parish on the northern shores of the Quequechan River, overlooking the Barnaby, Davis, and Chase Mills, just across the mucky river.

In 1963, the neighborhood we lived in contained a mixture of Portuguese and French Canadians. We lived in an apartment building a block south from Notre Dame Parish and a block north from the smaller Portuguese church, Espirito Santo. Compared to our much smaller, modest congregation, the French church sat impressively atop high ground and loomed over the entire Flint quarter, if not the entire city. Built of Fall River granite in 1906, the original church spires of Notre Dame stood thirty stories high and took sixteen years to build. The towers contained nine tons of bells that were forged in the Harvard Foundry in Ville-Dieu, France, and sounded a Westminster chime every fifteen minutes. One hundred feet wide and 235 feet long, the church’s interior was made to seat 1500 worshipers, with accommodations for 2000. Its twin green, tarnished, copper towers housed ten-foot diameter clocks. These could be seen from miles away. But it was the wistful bells I remember, sounding, beckoning its parishioners to service, or resonating the time of day in quarter hour increments. You could set your watch by them.

When the bells would sound, Mother would often look up at the wall clock, making sure it was keeping the correct time—Notre Dame time. Though we were members of the Portuguese congregation, it was Notre Dame de Lourdes, the Romanesque Corinthian French church one block from our front door, which looms impressively in my mind.

Apart from a place of worship, a job was the next necessity for a struggling family. In Fall River, with rich ethnic and diverse social life, but meager economic and educational standards, a job meant working in the textile mills. Though the mills were still running strong in the 1960s, the grandeur, strength, and capital they once commanded in Lizzie Borden’s time had all but faded. Most factories in Fall River in the 1960s were in the business of sewing garments, and sneeringly known as sweatshops—stitching such articles as shirts, suits, jackets, or curtains. At that time only a very few plants were still printing cloth, for which Fall River was king throughout the latter part of the nineteenth century. Almost everyone I knew had a parent or two who worked the sweatshop.

Just behind the deserted junkyard was the Fall River Lumber Yard on Weybosset Street. Heaps of neatly piled lumber planks sat in red-painted open sheds, where we would weave our compact bodies in a vigilant search for roving field mice or garden snakes—while the droning buzz of band saws resonated in the distant air. Here we romped among newly cut timber bulging off the backs of flatbed trucks, unmindfully enjoying the aromatic scent of freshly cut fir and oak, along with sweet, ripe pine sawdust. The nearest city park was much too far away, which made the old abandoned junkyard and the lumberyard just one of our many unseemly playgrounds.

Behind the house at 149 was yet another junkyard, the Gitlin Bothers, dealing in scrap metal and rags. Gitlin was located on Hargraves Street, across from Novek and Sons—still another junk dealer. (Today Gitlin Brothers is known as Mid City Scrap Iron and Salvage in Westport, Massachusetts.) Overlooking my bedroom on the west side of the house was the Hargraves Mill. In hot summer months, all the factory windows would be open and one could hear the constant whirring and jabbing oscillation of the busy sewing machines. The hurly-burly mill sounds carried on all day and were only broken by the clanging of the dinner bell, which signaled the start of lunch or the end of a work shift. As I waited for my mother, Laura, outside the Shelburne Shirt Factory on Alden Street where she was employed, the unshakable resonance made by the sewing machines became etched in memory.

Between the Hargraves Mill and our front porch, where Laura would sit tallying her piecemeal tickets from a hard day of sewing, sat a vacant lot. There, one could find abandoned stacks of splintered gray, wizened wood, concealed by two feet of overgrown weeds and dry grass. It was a place teaming with bees, dragonflies, grasshoppers, and wild flowers, along with lizards and garden snakes under every rock we kicked over. In one corner of this unoccupied parcel was a derelict and windowless shack, where inebriated drunks from Novek’s and Gitlin’s would lose consciousness, loosely clutching their spilled, empty bottles of tepid whisky. Here they would lay stifled, with the rancid smell of putrid urine. After they awoke and stumbled away, we would run over and thread our probing fingers through the dry meadow grass where they once dozed, in search of loose change that had fallen from the feverish pockets of their tattered wet trousers. I remember picking up pennies, nickels, and dimes, gripping them tightly. Not long out of pocket, they were still warm to the touch.

The portion of the East End we lived in at that time was populated by Lebanese emigrants along with a spattering of Polish families. Most referred to the area as Saint Anthony’s of the Desert Parish, after the Lebanese church on Quequechan Street. Much earlier in the century, this neighborhood was home to a small Jewish population and embraced two synagogues. One of these buildings of worship still stood on Weybosset Street when I was a child, less than a block from where we lived. By the time we moved there, all the Jewish families had long since moved to the northern part of the city.

Small ethnic stores could be found up and down Pleasant Street: a Polish delicatessen, a French bakery, a Lebanese restaurant, a Portuguese grocery. On the corner of Wamsutta and Quequechan Streets, 500 feet from our front door, sat the Polish Cooperative Store, where Mother shopped for her meats. I remember the manger being a kindly man who allowed me to wander and explore behind the counter where the floor was strewn with sawdust, soaking the splattered juices from the carved meats. Elongated chains of kielbasa and wedged slabs of red, marbled meat hung high above a glass display case filled with cheeses and cold cuts. The scent was one of sweet smoked sausage, spicy cheese, and bitter vinegar. The cluttered countertop held jars of fresh green pimpled pickles, sauerkraut, and sour pickled eggs. And, of course, there were Polish delicacies such as golumpkis and pirogues—treats for the heart.

MAKING GOOD FRIENDS

Eventually, I happily made a new friend in Tommy Hallal. Tommy lived in another three-decker, two buildings away. I often reminisce about Tommy and me sitting in endless weekends, as they all were to a child, watching baseball on a black and white television set with his wailing Nana—his frail, slender grandmother, who often sat in a small chair two feet from the TV. An ardent Boston Red Sox fan, Nana would jump up from her chair, waving her arms in protest, lambasting rookie Carl Yastrzemski for swinging the bat three times in a row, never contacting the ball. On chilly winter days, we would visit Tommy’s uncle at Hallal’s Dry Cleaners, where he worked on Pleasant Street, and where the sterile, crisp scent of bursting steam and freshly pressed clothes warmed our frosted cheeks and tingled our noses.

We played endless games of stickball in Tommy’s driveway using an old broken broomstick and a pinky, as we called them, a very bouncy pink rubber ball; or we could be found cheating at hopscotch with the girls who, to their torment, would have to give chase in an attempt to retrieve their white chalk—always white. After school, we played kick ball until the late hours of the day, the girls against the boys, until the streetlights came on and we all ran home, lest we turn to stone.

At supper, we would sit in Tommy’s back yard under the grape arbor with his mom, dad, and cousins, eating homemade tabouli wrapped in tangy grape leaves that grew freely above our heads. Afterwards, we would incessantly beg for ice cream, then work it all off with multicolored hula hoops, or engage in a squirt gun battle with brightly colored plastic pistols, shaped like space ray guns—soaked to the bone running, giggling, chasing, and puffing, until our sides ached or our parents refused to fill our guns any longer.

On rainy days, we amused ourselves indoors with electric trains or erector sets, and if we were bored with those, Tommy would take out his parent’s 45-rpm records and we would lounge around listening to such greats as The Four Seasons, The Beach Boys, and The Ventures, and chasing Tommy’s sister Barbara and her friends away—until Nana took all she could take, intervened, and drove us all away.

In the summer, I would tag along with Tommy and his sisters to his Nana’s cottage in Swansea, on the shores of the Coles River, where we all escaped the city’s heat and immersed ourselves in the study of horse crabs and spitting clams along a seaweed shore. At high tide, swimming was the order of the day and on the ride home it was ice cream all around.

ON THE MOVE

It was not long before we had to move—just as I was feeling settled in. Although the move was less than ten blocks, to an eleven year old, our new address may as well have been ten miles away. I never saw Tommy Hallal again.

I was a little older and wiser, but not by much, and the move meant searching out new friendships and scoping out safe territory still once again. The new neighborhood was far from an improvement. The bedroom I occupied included a window with a panoramic vista of the Quequechan River basin and the granite mills that lined its swampy shores. One block away was Webster Street, where the infamous Webster Street gang loitered. It was one of two somewhat organized street gangs in Fall River at the time—the other being the Eighth Street gang down by the center of town. Though far from being as dangerous as inner city gangs are today, I can still remember being brashly rerouted into a remote alley or empty store front and having my pockets rifled and my weekly allowance confiscated. One time in particular, when a group of thugs seized me by the collar and dragged me behind the Friendship Café, is branded in memory. Immediately, the oldest boy began going through my trousers while the other two held me down by the arms, turning all my pockets inside out. When nothing was discovered, the brute and his young associates pushed me against the wall and sauntered away. Just when I theorized I was safe, one of them returned, a boy named Kid Ray—the smallest one. Placing his nose up to mine in a ruffian’s challenge, Ray stared me down and then backed away. Then, unexpectedly, he lunged forward and punched me squarely on the nose. (A couple years later, this same boy drowned while swimming at the Swansea Dam over by Case High School in Swansea.)

Primarily a French neighborhood, our new place was situated on a busy main street. Number 1619 Pleasant Street was a four-story white and red brick building located on the corner of Choate and Pleasant Streets. We lived on the upper-most level. The main entrance was around one side by way of a large and meandering, rickety wooden stairwell, with long sweeping porches. Emigrant renters, mothers and daughters, were often seen resting on their elbows along porch railings, passing the time of day and scrutinizing traffic along busy Pleasant Street. Behind them, damp clothing, held by miniature wooden pegs, hung and fluttered in the breeze. Zigzagging weathered, gray clotheslines adorned all three elevated verandas. At the foot of Choate Street, just a block away, stood the yellow brick Espirito Santo Church and its red brick Catholic school, where I attended class.

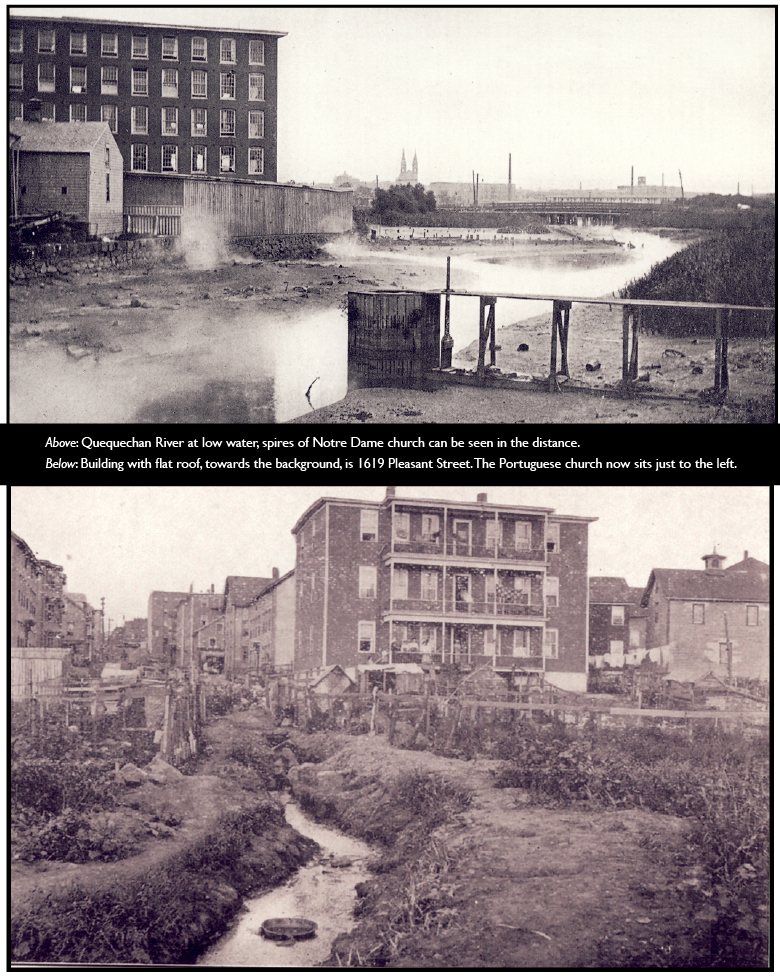

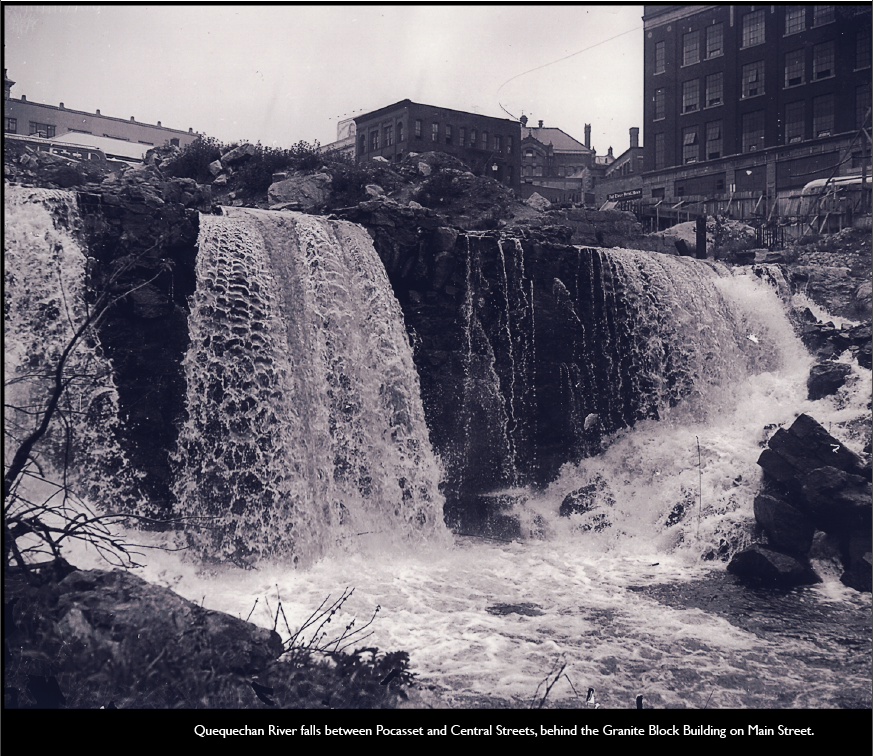

Behind the church, and somewhat east of it, were old guttered culverts, where oily street drainage, along with crude sewage and solid waste matter, flowed freely into the Quequechan River. Once in the tributary, this foul soup fermented in the balmy summer sun into a gray-black broth, which was further intensified by the pernicious dyes and caustic chemicals that spewed from the textile mills, past and present, and from the sludge deposits that coated the thick mucky river floor. All this putrid and tainted leaden water slowly drifted downstream and fed a number of waterfalls that existed at the center of downtown.

For us, the Quequechan River became our playground. Here we went rafting and cast our lines, using fishing rods we made from the branches of a new maple and kite string. The river was a place where greasy black catfish would prod their little whiskered faces to the water’s surface as if gasping for air. These poor creatures lived a life of perdition and didn’t even know it. In many respects, our childhood could be said to be the same.

On Main Street, across from City Hall, the river’s sudsy rust-colored water cascaded down a tall waterfall just behind the Granite Block Building. The river floor below was littered with the remains of granite building blocks, left over from the old Pocasset Mills, which burnt to the ground in the great 1928 Fall River fire. Here one could smell the pungent, noxious odors fanned by the cascading water and shamefully delivered from upstream, before the once pristine Quequechan wed the larger briny Taunton River four blocks below the hill.

MOM AND POP SHOPPING

In the late 1950s and early 60s, so-called supermarkets were just starting up. At that time, mom and pop proprietors managed most food markets. Eggs, milk, cheese, and bread were still delivered to one’s doorstep. It was a time when the milkman was just as popular as the mailman, and farmers sold fresh locally grown fruits and vegetables from the back of a farm truck along city streets. Manny’s Superette was a good example of a small mom and pop market. Manny’s occupied the store on the ground floor of our tenement house. But most of our food shopping was accomplished a block away at Camara Brothers Grocers. Camara’s was a small claustrophobic place with very narrow aisles. Canned food and boxes of dry goods wallpapered the walls from floor to ceiling. As a child, I was always captivated by the long stick with pinching tongs the grocer used for retrieving a box of Cheerios from one of the towering shelves. These quaint markets were scattered all over American cities. A neighborhood grocer knew his shoppers by name, and credit was freely extended to good customers and posted into a ledger until payday. One could probably fit fifty of these small outlets into one of today’s mega-supermarkets—but one could never duplicate the personal courtesy or regard you received in one of these small community markets. On one corner of Choate and Pleasant stood Mike’s Variety. Mike, a short, jumpy, and grumpy fellow, appeared quite unsuitable for his profession as the manager of a small variety store. Children would shop at Mike’s for penny candy and take up an entire fifteen minutes in deciding how to spend ten pennies. This sort of practice taxed Mike’s resolve, and usually went something like this:

LITTLE GIRL: (reaching up she spills her pennies on the scuffed glass display counter), “Candy please. Let’s see—I’ll have one of thooosse, a squirrel nut—two twisty licorice sticks, ahhhhh, Mary Jaaaane.”

A minute or two passes. The little girl’s younger brother pushes against the smudgy glass display case with a tiny, bent, and wrinkled finger.

LITTLE BOY: “Get sumah those, sumah those Karen, get sumah those.”

MIKE: “Come on, come on, little girl, I haven’t all day.”(Strangely enough, he did.) “You little boy, don’t lean on that glass!”

LITTLE GIRL: “How much money do I have left?”

She reaches over her head to the glass counter, trying to tally the remaining change.

MIKE: (pushing the coins with his large, stubby fingers), “You have six cents left little girl, S-I-X—six, now hurry, I have things to do.” (Which he certainly did not.)

The little girl tosses her little blond head from side to side, rolling and lurching her shoulders, humming. Another 2 or 3 minutes pass. She dances in place, intensely surveying the goods.

LITTLE GIRL: “Ok, let’s see, hmmm—a bazooka.”

LITTLE BOY: “Karen, Karen, get da buttin candy, please, please, buttin candy.”

LITTLE GIRL: “No, they stick to the paper. I na-wana eat paper.”

LITTLE BOY: (poking at the glass enthusiastically), “Get da candy cigarettes—da ones with real smoke—yeah, get sumha those.”

LITTLE GIRL: (turning abruptly), “No, shut up, I’m thinkin.”

Mike, who was not cut out for such childish procurement, abandons all calm and civil restraint. With feisty determination, he pushes open wide the display case door, with its noisy raspy ball bearing track, clutches candy at random, and slams them on the counter.

MIKE: “You’ll have one of these, one of these and one of those—there, done! Your money’s all gone now.”

LITTLE GIRL: “But, but, I have another penny?”

The little girl steps back in bewilderment, clutching her shinny pink purse as it waves about. Before she could say anything more, Mike quickly tosses the candy into a small brown paper bag, circles the counter, tucks the bag into the little girl’s hand, and escorts his unhappy pint-size patrons out the door.

I would like to think Mike didn’t hear little Karen—but I’m afraid he chose to ignore her.

As he opens the door and pushes the two young shoppers out, two more children happily march in—smiles on their faces and clutching pennies. After all, Mike’s was the place to go for penny candy.

Some time later, Mike would make up nickel bags, which he would fill with an assortment of penny candy, so as to hurry the children along. But, you never knew what you were going to get. For a youngster, a visit to Mike’s Variety was always a diplomatic exploit and a trying lesson in how to compromise with adults.

As a youth, one of our favorite ventures was a jaunt to Central Ice Cream, located three blocks away on Eastern Avenue. Its pudgy-faced, jolly owner always greeted us with a sincere smile. Here we would lounge, spending our scant weekly allowance licking ice cream to the loud drone of electric fans, which moved the hot summer air from one end of the room to the other. The counter, sporting a row of rickety stools, sat below a series of sticky flypaper, which hung from the ceiling. For an innocent boy of ten, there was nothing so grand as eating a strawberry ice cream cone and observing tussling flies skirmishing for life, while stuck to shimmering, sticky, ocher-colored ribbons.

If Central Ice Cream was closed, we would stride across the street to Vaillancourt’s Variety, also known for their assortment of tasty-flavored ice cream—and yes, penny candy. As one walked in the front door, the first attraction was the penny candy display case to the left. Every variety store had one. Beyond the splendid buffet of sweets was a long serving counter. A portion of it was made up of stainless steel freezers, with multiple small lids. Inside were large round containers filled with multicolored ice cream.

Behind the counter stood the Vaillancourts, a thin little man with a long steely mortician face, and two elderly stern-faced women. They could usually be found conversing with customers, or each other, in French. Soft spoken, they appeared to be very gentle people, though they rarely smiled. The older female, a squat old women who appeared well into her seventies, limped badly while walking on her elbows along the shallow counter. She rarely spoke. Instead, she would lean over, stare at us with blank droopy eyes, and ask us what we wanted by twitching her head and lifting her bristly eyebrows. When she flung one of the freezer lids open we could not help but lean in closer, and eagerly peer down at the canisters containing the chilled creamy flavors, taking in the cool sweet scent of hard, frosted cream. The foggy freezer mist nipped our smiling faces—boy did that old lady pile it on!

Behind the counter stood the Vaillancourts, a thin little man with a long steely mortician face, and two elderly stern-faced women. They could usually be found conversing with customers, or each other, in French. Soft spoken, they appeared to be very gentle people, though they rarely smiled. The older female, a squat old women who appeared well into her seventies, limped badly while walking on her elbows along the shallow counter. She rarely spoke. Instead, she would lean over, stare at us with blank droopy eyes, and ask us what we wanted by twitching her head and lifting her bristly eyebrows. When she flung one of the freezer lids open we could not help but lean in closer, and eagerly peer down at the canisters containing the chilled creamy flavors, taking in the cool sweet scent of hard, frosted cream. The foggy freezer mist nipped our smiling faces—boy did that old lady pile it on!

At that time, Eastern Avenue contained an extra-wide rubble stone median strip down the center of the road. It was lined with mammoth maples that supplied welcoming shade to unkempt green park benches. We would sit by one of these aging but majestic trees, licking our wonderful tasty treats, and allowing the cold delight to drip down our tacky fingers and tickle our arms. Across from Vaillancourt’s, on the corner of Eastern Avenue and Pleasant Street, just beyond the statue of the reflective Prince Henry, the Portuguese navigator, was an impressive polished granite water fountain. At one time, these fountains could be found all over the city, mostly at street intersections, or in parks. Though to a small child most were about chin level, we had no trouble jumping up, hanging off our elbows, and guzzling. Here we would quench our ice cream thirst and cool ourselves by jamming our fingers in the water nozzle, squirting each other along with passing cars. Subsequently, once our bellies were filled, we would end up back at Vaillancourt’s thumbing with sticky wet fingers through the latest issue of Superman, Fantastic Four, or Captain America, which were embraced by spinning wire racks, until, to our dismay, the stiff but genteel Mr. Vaillancourt ushered us out the door.

Throughout Pleasant Street there existed a diverse patchwork of retail stores. These included Borges Variety, White Rose Bakery, Flint Fish Market, Family Meat Outlet, Couture’s Barber Shop, Adams Drugs, Woolworth’s, and George’s Poultry—where we would hand-pick a live turkey in the afternoon and have it dressed and ready for Thanksgiving the next morning. All these establishments were within a couple blocks of our tenement house. But, it was the countless saloons and barrooms up and down Pleasant Street that had a memorable, if not detrimental, influence on a young boy’s mind.

A SALOON FOR EVERY OCCASION

The old neighborhood I lived in was an unhealthy place for a child to mature. My experience of Pleasant Street was depraved and menacing at best, and, at times, hostile and injurious at worst. Though some have fond memories of growing up in the Flint, I do not. My most vivid memory was of the countless saloons and bars that lined the entire length of Pleasant Street. From Quarry to Barlow Street alone, just about a mile, there were a dozen saloons. These were called cafés, but were far from what one would imagine a café to be. All were taverns and barrooms, hangouts for drunks and day drinkers.

Cafés that were situated on corner lots usually included a side entrance with a sign that designated it as a “Ladies Entrance.” Inside, a couple of booths were petitioned off from the bar area where a wife or girlfriend could sit and inconspicuously nurse a drink. Within three quarters of a mile from our apartment stood the following drinking establishments:

Pleasant Café,

Massasoit Café,

Strand Café,

Beacon Café,

East End Café,

Buddie’s Café,

Mahogany Café,

Webster Café,

Ringside Café,

Green Lantern Café,

Blue Bird Café,

and the Friendship Café.

Further down Pleasant Street, and closer to downtown, were still more. These included:

Pigeon’s Café,

Roma Café,

Troy Café,

Midway Café,

Crown Café,

and Yellowstone Café.

This did not include private clubs, most of which also served alcohol. Such institutions were the

East End Sportsman Club,

Lusitano Club,

Flint Social Club,

Lincoln Club,

Stafford Square Club—all on Pleasant Street.

Within a block or less of Pleasant Street one could find the

Dover Club,

American Syrian Cub,

St. Michael’s Club,

Madeira Club,

and the Canadian Club.

All these drinking establishments sat less than a mile and a half from our front door. On Pleasant Street, alcohol flowed more freely than the waters of the Quequechan.

Post World War II Fall River was known as a party town. Countless sailors from the naval base in Newport would arrive to indulge themselves in entertainment, dance, and drink in the many saloons and clubs that were located throughout the downtown area. Older residents I have met over the years each had their own yarns about the clubs along Central Street downtown. One explained why Fall River cafés were so popular. The story was about a fellow who had picked up four hitchhikers from Fall River, all girls, and was later assaulted below the waistline with a hatpin and raped by all four women. The story circled throughout the naval base in Newport and every sailor wanted to call on Fall River. Whether based in truth or folklore, I first heard the story from a personal friend, Joe, a sailor and WWII veteran. At first, I thought it was one of Joe’s riveting tales, of which he has many, until I heard the same story from another WWII sailor years later. Somewhat insulted when I laughed, he swore the story was based in truth. Was it?

At that time, two of the most notorious Fall River Clubs were the Latin Quarter and the Copa Lounge on Central Street. This was long before I was born. Personally, I remember the prostitutes of the late 1960s and early 70s outside Charlie’s Café, and the notorious Pier 14 Lounge on Bedford Street. In the shadows of Seventh Street sat the pimp’s neon lime-green Cadillac, sporting tinted windows and extra wide white-wall tires. Like a scene from the TV series Starsky and Hutch, the dark-skinned, lanky driver could be often seen leaving his car, dressed in a long fur coat and white cowboy hat, and entering the Pier 14 Café. Other times, the bartender of the Golden Pheasant Café could be seen selling liquor to patrons on Sunday from a rear door, where bottles and greenbacks were exchanged with smiles. Like Pleasant Street, the downtown and south end areas had their own roster of clubs, with such names as:

Acorn Café,

Park Café,

Mike’s Tavern,

Circus Lounge,

Washington Café,

and the Knickerbocker Café.

The Bedford Street district, an entanglement of business and residential buildings, had its own share of saloons and, in many respects, was a more harmful place for a young child to experience his youth than its sister, Pleasant Street. These so-called cafés became a source of curiosity and a twisted sideshow for a pre-teen. Add to this picture an alcoholic parent, and life on the streets, and at home, becomes very virulent.

As a four-year-old, I recall mother rushing ahead, all the while towing me along tightly by the hand. I fervently worked my little legs trying to keep pace, unsure of the urgency. We traveled a greater part of Pleasant Street late into the night, from saloon to saloon, as she searched for Father. It was payday and she challenged the clock, trying to locate the old guy before he spent his entire paycheck on booze, cards, or dominos. Too proud or shamed to go inside one of these drinking establishments, mother would lift me up onto her shoulders. There I would spy past elevated neon signs and saloon windows, all the while abiding by her stern command to, “see if your father is in there.”

Once she found him, the sight was not a pretty one, as pride and shame were swept aside, replaced by conflict, strife, and much yelling. At the age of four, I frequented some of these taverns myself—not alone, of course. As father sipped his Narragansett beer, a local brew, and played dominos with his companions, I recall sitting on the wet mahogany bar in short pants, with the cold, polished damp surface nipping the backs of my legs, while drunks ruffled my hair and tipsy patrons bought me peanuts and a cola and engaged me in slurry conversation. I liked it when they gave me pennies to feed the gumball machine.

These were tough rumble-tumble places. Flying fists and brawls were the routine order of the day. Visits to the saloons by the “Paddy Wagon” were a common occurrence. I remember the police wagon coming to a screeching halt, just feet from our home, along with a couple black and whites and a group of nightstick bluecoats, their badges gleaming in the night street lights, marching into the saloon. Soon, bemused patrons could be seen teetering out the café door, while others were escorted by the arm or dragged by the neck and thrown into the back of the dark-colored panel truck.

APPRENTICE TO A SHOE SHINE BOY

The day after we moved into 1619 Pleasant Street, I was looking down from our fourth level porch when I saw a young blonde boy below. I hurried down the stairs, contemplating how I could make a new friend. One plan I had was to show him my prized Indian Head nickel. When I approached, he was indulging himself with a handful of pumpkin seeds, which he scooped out of a plain white wrapper. Pumpkin seeds were a common Portuguese snack, roasted in a red pepper paste along with various spices and salt. Ultimately, he offered me the wrinkled wrapper full of seeds and I let him have my Indian nickel. After that day, we became close friends for life.

The little blond boy, Johnny Miranda, lived on the second floor of 1619. Son of Portuguese emigrants, Johnny was a wizard with his hands, even as a child. He taught me how to make scooters from old roller skates, soap box cars built from discarded grape crates with wheels off an old abandoned baby carriage, and a bow and arrow, using fishing line, pigeon feathers, and tree saplings, which grew in an empty lot next door.

One day, Johnny appeared with a shoeshine box that he constructed himself, made from the wood from grape crates. Wine making was a widespread practice by Portuguese emigrants in New England. During wine making season, empty purple-stained wooden crates could be found stacked up by the side of the road on trash day all over Fall River. Hence, Johnny, at the age of twelve, had started a little vocation—a shoeshine business. I assisted as his boy apprentice and helper.

In the early 1960s, there were still four shoeshine parlors in Fall River, a pair were within two blocks of our apartment building. One, Pleasant Street Shoe Shine, was directly across the street from our apartment. The largest, and best known, was the Academy Shoe Shine Parlor in the Borden Block downtown, just across from the A.J. Borden Building. As a child, I remember peeping into the Academy at the elevated chairs, where patrons, mostly men in suits and ties, sat reading the Herald while having their shoes cared for. Just outside Academy Shoe, along South Main Street, was the main bus stop, which dispatched to all locations in the city and beyond. Nine or ten buses would line along the curb, while drivers spun their Rolodex street signs, changing destinations. Bus traffic was very good for the shoeshine business.

Curiously enough, there were no shoeshine parlors in 1892, during Lizzie Borden’s day. Public stands and parlors did not come into being until after the early 1900s, when commercial shoe polishing products began to appear. Nothing did more for the public shoeshine industry than a world war. WWI and WWII were boom times for the shoeshine trade, made so by the ever-lasting endeavor to achieve the perfect spit shine. Once the armed forces dressed down and retired to civilian life, the search continued for a faultless luster. This ready-made customer helped further drive the trade. Today, it’s all about sneakers, running shoes, tennis shoes, and rubber covered footwear that requires only soap and water. With very few exceptions, like airports, or in very large cities, few of these shoeshine stands exist.

Once Johnny began his new profession, I tagged along, undertaking the humble task of handing him shoe polish and brushes from his carefully crafted utility box. Ultimately, the most lucrative location in which to practice the shoeshine service was the saloon. The first time I recall accompanying him was to the Green Lantern Café, five blocks from our residence. Cafés closer to home were avoided, to prevent the possibility of running into our fathers. The little shoeshine business was a clandestine endeavor, and if our parents had discovered it, or that we were waiting in drinking establishments, it would mean the strap.

The Green Lantern Café was, in many respects, a landmark in the upper Flint at the time. It was one of the last bars towards the end of Pleasant Street, in a section of the Flint called Bogle Hill. Its facade was adorned with a conspicuously large green lantern light over its front entrance. These unsavory waterholes were usually dank and dark places, with the pungent musty fetor of old rancid beer and stale tobacco. Light inside these places, like some of its customers, was always kept subdued. In warm summer months, the only illumination came from sunlight creeping in the front door, which was regularly propped open until closing hours. Peering inside, one came away with the impression that the same individual sat in every café—a willowy, dark, leathery skinned fellow. This clone always sat perched on the edge of his stool at the end of the bar near the entrance. Slouching on his elbows, a half-filled glass of beer sat by an overflowing ashtray. With a smoldering cigarette burnt down to his knuckles, and bathed in billows of white and blue smoke, he sat alone staring up at the ceiling, as if carefully contemplating a grand conspiracy. Occasionally, he would squint out the open saloon door, with a glazed expression of contentment, as the bartender topped off his half foamy glass.

To my astonishment, women could be seen sitting in a booth or table toward the back of the badly lit room, or off in a shadowy corner. These painted ladies always stood out, with their white-caked faces, brilliant red lips, and gracefully poised cigarettes, between ruby nails and ringed crinkled fingers. The sounds in these forbidding dens of drink were usually of cracking billiards, echoing laughter, and loud chatter and gibberish, in French, Portuguese and English. As kids, we felt it was a great adventure to go inside these watering holes and explore. It was a temptation and curiosity we could not avoid; to observe how our fathers played. As a shoeshine boy, we had the perfect excuse, and admittance was almost always assured.

A shoeshine was ten cents. As business improved, the fee soon went up to fifteen. Not all saloon owners or bartenders allowed us inside, but customers could still be found close by. Many of these taverns had men loitering outside, taking a deserved break from a hard day of drinking. Most of these well-lubricated fellows could be considered unpredictable. One such sot paid us for service, and then sent us away after Johnny shined only one shoe. Some were very happy to see us and treated us like long lost sons. Others would just stare down with a haunting, glassy, expired gaze, then suddenly and unexpectedly mumble us away. But not all customers appeared inebriated. Some gents were very attentive to the level of service they received. Close inspection of their feet demonstrated that the vigilant customer was still on his first drink. Johnny had to be very careful not to get black polish on white socks. My shrewd budding employer carefully placed a piece of cardboard, which he cut from old shoeboxes, between the shoe and sock to avoid any such accidents. Whether leather or suede, there was no shoe that did not receive care from Johnny the bootblack.

UPON INTROSPECTION AND REFLECTION

Today, all the saloons are long gone and Pleasant Street is a very different place, but with an entirely new set of problems. The number of saloons in Fall River was both a direct reflection of the class structure and the social and economic complexion of a great portion of the city, as well as a significant reason why the city has never gotten over its growing pains in those early years. The Flint neighborhood was a less-than-ideal place for a wide-eyed youngster to spend his valued youth. Lessons acquired as a boy were reluctantly rooted in street savvy, and held little to no value nor any practical application later in life. To have only a painted rosy picture of life in Fall River and talk of the good times is to ignore a city’s disfigured past.

In my description of the East End, I have included some of the best of times, for there were many, and tried not to confess all the worst of times, for there were also many. Of course, I can only speak for my little corner of Fall River at that time, and my personal perceptions and walk through life in pre-puberty years. Much of growing up healthy in mind, spirit, and body has its lasting origins at home and in honored family values. But these values can be provoked by detrimental challenges and outside forces. When parents work long hours and lack the proper time to lend their children a healthy upbringing—when money for the bare essentials is always scarce, and children are cursed with an alcoholic parent, growing up can have harmful consequences. In my case, add to this well over thirty taverns within a mile and a half from my front door, and city streets can have a transformative impact on a young, fledgling mind.

This was the reality for many who had spent their adolescent years in a deleterious part of the inner city. This was true of Kid Ray and his two brothers, all victims who never reached the age of thirty. (Neither one of whom died from illness.) I would be less than honest if I did not admit to be one who can recall many strained memories of youth—memories which, at times, blemished a boyhood diary. Family politics aside, the outcome was not all based in gloom and doom, nor did everyone have the same experiences, or digested life in Fall River in the same manner. And, though some of my observations as a child may appear critical and dire, their consequences were smothered by an auspicious upbringing, one managed by a strong and loving matriarch. The same case could be made for many who I grew up with.

Many close friends who lived in the Flint went on to have long, flourishing careers. Thomas (Tommy) Hallal became a successful attorney. John (Johnny) Miranda is head of his department at a local high school. A city of 89,000 cannot help but produce its share of success stories. Some are quite recent, and can be found in individuals such as Emeril Lagasse, Morton Dean, E. J. Dionne, Joe Raposo, Greg Gagne, George Stephanopoulos, and Wendy Moniz—all Fall River natives who have made the big time.

As a young teenager, all my ties were eventually broken with the East End and the Espirito Santo Parish. In my late teens, we became members of the Santo Christo Parish on Columbia Street, another Portuguese church less than 200 feet from where Lizzie Borden was born. Faith continued to be a vital anchor to which my parents tied their lives. We continued to be on the move. Ironically, after living in three separate locations in the North End, we ended back on Pleasant Street, three blocks away from the Green Lantern and Ringside Cafés. By this time, most all the cafés and saloons along Pleasant Street were gone. The old French church had burnt to the ground in a spectacular blaze, taking with it over a dozen buildings and apartment houses. Central Ice Cream is now part of a pizza business, and though the French variety store, Vaillancourt’s, is still at the same location, it is doubtful its new Lebanese owners speak any French.

Years later, I purchased the Davenport house on French Street. Never having more than a passing interest in Lizzie Borden, I had discovered Maplecroft where Miss Lizzie once lived, and, by serendipity, I had acquired one of her properties. The contradictions between life on Pleasant and French Streets today, and when Lizzie was alive, have not changed all that much. The Highlands, as Lizzie’s old neighborhood is known, has always been a more affluent, and safer, place to live than Pleasant Street.

The conventional, easy life of Lizzie Borden, and the average hard working mill hand in Fall River, could not have less in common. (This will be made plain in the long-awaited book Parallel Lives, due to be published by the Fall River Historical Society sometime in 2011.) Though far from a life of poverty, the average family in Fall River strived to keep soles on the bottom of their children’s shoes and ample sustenance on the dinner table. Everyday necessities, such as cars, phones, or air conditioners, were lavish luxuries and out of reach for most when I was growing up.

As a child, I grew up never quite sure where Lizzie Borden had lived before and after the murders, but, like every person in Fall River, I was very familiar with the famous Lizzie Borden doggerel, “Lizzie Borden took an axe.” Very little attention was given by the average Fall River native to the crime or its considerable history, unlike today, when Lizzie sustains the majority of the tourist trade in Fall River. In the 1960s, talking about the sordid topic was an exercise in vulgarity and poor etiquette—and ill advised. To identify with a criminal was ludicrous and outrageous, even if that criminal was found innocent, which no one in Fall River believed. Stirring an old pot by discussing it did not accomplish much of anything.

Many who have read about Lizzie Borden and Fall River have formed their own spurious perspective of what life in Fall River was really like, with its large stately Victorian homes, park-like cemeteries, and impressive granite public buildings. But, to Portuguese fathers, French daughters, and the Irish sons of European settlers who struggled in the mills throughout the last two centuries, life could not have been more divergent. My life, and Lizzie Borden’s life, could not have been more contrary, or more unparallel.