by Bill Goncalo

First published in August/September, 2007, Volume 4, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Those persons who have the occasion to drive through Fall River on Interstate 195 often remark on the presence of the numerous granite mills that flank the highway. However, those who cross the city on Route 24 get a spectacular view of the Watuppa Pond. While this highway is not lined with mills, many motorists do notice a single set of granite ruins on the shore of the North Watuppa, the city’s cherished water supply. Many who pass speculate fancifully on just what the remains could have been. A castle? A factory? Prison?

Truthfully, few Fall River residents know the origins of the remains. Those who know something about the area will say that it is “Interlachen.” Others will report that the nearly forty-foot walls were from the home of “Spencer Borden.” While Spencer Borden did live nearby, the remains do not belong to the Borden mansion. In fact, the foundation of the now demolished Borden mansion is about a quarter of a mile northeast from that location. It is not Interlachen, which was the name of the Borden’s nearby estate that borders the ruins. The remains are, in fact, what is left of an ice house constructed on the shore of the pond in 1864. The ruins serve as a lens to examine the nation’s natural ice industry as it proliferated in Fall River during the 18th and early 19th centuries.

While not obvious at first glance, the ice house is actually on the shore of an island — Cunningham’s Island to be precise — so named after Benjamin P. Cunningham, a successful local merchant who lived on the island in the middle 19th century. The island, once a peninsula, only became an island in 1832 when the town’s mill owners constructed a dam on the Quequechan River. While the dam assured water for mill use during the dry summer months, it also raised the pond’s level two feet, flooding many low areas around the pond’s edge (Report 17-18). The rising water eventually encircled the island, which remained connected to New Boston Road only by a granite and rubble causeway. A separate causeway, constructed on the north side of the island towards the end of the century, is currently under the still high waters of the pond.

Sometime after 1853, Cunningham moved to Providence and the island came into the hands of Robert Cook, becoming a small part of the larger Cook Farm. For most New Englanders, farms conjure a predictable image: barn, livestock, silo, crops, etc. However, Cook’s farm was different. Moreover, Cook harvested neither corn, potatoes, nor oats from the island. Cook’s most profitable crop did not even require soil. Robert Cook harvested ice.

The domestic use of natural ice —ice taken from ponds and rivers — was not new. Ice had been primitively collected and stored for use during summer months by individual families in America and Europe for hundreds of years. Thomas Jefferson, who had an affinity for ice cream, even included two ice houses in his plans for Monticello (Cummings 2). Ice as a cash crop, however, was a new idea. While this might seem strange to us today, the concept is hardly as quirky as it appeared in the early 1800s when the profitability of selling ice was first demonstrated by Frederic Tudor from Boston. Much to the amusement of his contemporaries, Tudor fit-out a ship to transport ice harvested from a pond in Boston for sale in Cuba. His first shipments were financial disasters because he lost much of his cargo to melting. Tudor, undaunted, persevered and learned from these first painful lessons. He perfected the technology associated with ice harvesting, storing, and distribution, until in a very short time his business operations were an unqualified success.

In 1834, the originator of this extended trade sent a first cargo to Rio de Janeiro, in Brazil. Until about 1836, the whole business of shipping ice by sea to distant ports was carried on almost exclusively by Mr. Tudor, and his success earned for him the well-deserved title of the Ice King of the world. About 1837, his success attracted others to engage in the business (Hall 3).

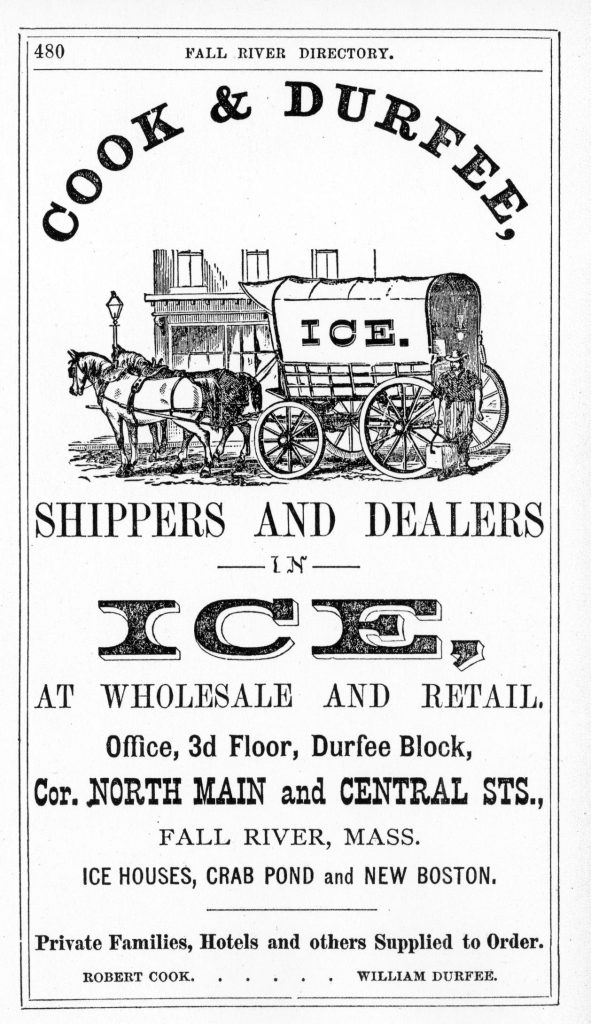

This building is in the rear of Fourth, along Fifth Street.

Tudor’s example was not lost on Robert Cook and his business partner William Durfee. According to Fenner’s History of Fall River, Cook and Durfee began keeping commercial ice houses in Fall River as early as 1838, “in a small stone building still standing on Pleasant Street, near the Narrows” (240). The 1853 Fall River City Directory notes that the men operated ice houses at Crab Pond (a small body of water near the present day Tillotson Complex on Ferry Street) and on Hartwell street, where they harvested ice from the Quequechan River that flowed nearby. The Cook and Durfee Ice Company was very nearly the only ice supplier in town during this period, and business was good. It was so good, that in 1864 they built what can only be called an extravagant granite ice house (most ice houses were constructed of wood) at New Boston Road on the Watuppa.

The techniques used for harvesting and storing ice were fairly well known; Cook and Durfee undoubtedly used the tools and harvesting methods popular at the time. The ice harvest season began in January and was generally over by the end of February, although some companies were able to harvest a second crop as late as March when temperatures permitted. On the other hand, operations were also sometimes limited due to mild winter temperatures. Ice harvesters did not want to be at the mercy of Mother Nature to obtain quality ice, so, like other agricultural products, ice soon came to be cultivated. For instance, before the harvest, considerable time was spent clearing snow from the surface of the ice. Besides inhibiting freezing, snow tended to cloud the ice. Clear ice, free of air bubbles, was always preferred.

When temperatures were mild and ice was forming slowly, the ice would often be “tapped” to facilitate formation. Tapping involved boring holes though the ice to force fresh water onto the surface where it would freeze more quickly and add thickness to thin ice. The new ice formed was “not considered as necessarily inferior” in quality (Hall 8), and was at least of a thickness suitable for harvest. If ice were to be harvested from the Watuppa in our relatively warmer present day winters, this is precisely what would need to be done. And the weather is warmer, at least as suggested by the journal of David M. Anthony, Sr., a Fall River merchant and founding partner of the Anthony, Swift & Company (now Swift Premium brand meats). Anthony depended on the natural ice harvest for his meat packing houses and kept detailed journals describing yearly ice harvests. In an entry for January 25, 1888, Anthony notes that his crews finished icing on that day and that the ice was thirteen inches thick. And, unlike Fall River winters in the 21st century, Anthony’s journal describes generally frigid temperatures and cold snaps that dropped local temperatures below zero for days at a time.

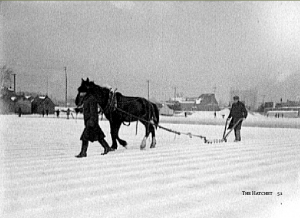

When the ice was of suitable thickness—usually six inches or greater—workers would set about clearing snow from the ice one last time. The workers would then use a “snow ice plane” to plane the soft “snow ice” from its surface. The plane worked very much like a plane used on wood and involved dragging an angled blade over the surface of the ice to make it smooth. This plane, however, was much larger than a carpenter’s plane, in that it accommodated an ice worker who would ride on the sled-like tool as it was pulled by a horse across the ice.

After planing the ice, a “field” would be marked off square with surveyor’s precision (Hall 8). Using a bladed marker, a single three inch deep groove was cut into the ice along one side of the field. After the first groove was cut, a “sliding guide” was placed in the original groove, and it guided the bladed marker in cutting a precise and parallel line (usually 22 inches apart) for the next three inch groove. By repeating this process in both directions, a whole ice field would be marked into regular 22 inch squares (sometimes larger in areas with rail transportation), ready for cutting by horse drawn “ice plow” that would cut the ice through nearly its full thickness.

After this plowing was complete, workers used breaker bars to break off long strips of ice that were then floated to the ice house through a previously cut channel. The ice was next cut into squares using ice saws, and then floated onto a sloped conveyor belt called an “elevator” that would lift the ice into the ice house. Once inside, the square blocks were fit in like tiles on the floor of the ice house, insulated from the walls by paper and sawdust. The ice house had only a ground floor, and ice was stacked in layers from the floor nearly up to the roof. Doorways spanning the entire height of the house were closed up incrementally as the stacked ice rose.

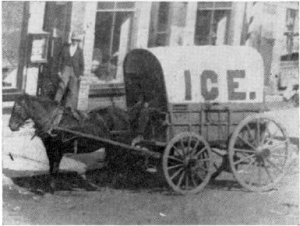

When the whole house was filled, it would be sealed until ice was needed in the warmer months (May through October). Then it would be delivered throughout the city by wagon to both homes and businesses. The stored ice easily kept through the summer, and a well packed and insulated ice house could preserve ice through two summers if needed. In fact, when ice houses occasionally caught on fire and burned (remember the sawdust insulation), it wasn’t uncommon to have the ice remain stacked and intact long after the house around it had burned to the ground.

Initially, Cook and Durfee had no real competition and dominated the Fall River industry until the late 19th century when several new ice houses sprang up on both the North and South Watuppa ponds. The reason for this expansion bears some explanation. Initially, a large part of the city’s ice company’s business involved filling ice boxes in private residences. However, the commercial demand for ice increased with the proliferation of trade and

the transportation of fresh fish, meats, fruits, vegetables, and milk, and the manufacture and storage of beer, ale, wine, and butter; and these and other industries have led to even a greater consumption of ice than that which is called for by the gratification of luxurious tastes (Hall 2).

from the 1857 Fall River City Directory.

Fall River’s industries grew exponentially during the latter half of the 19th century—textile factories primarily. While the textile industry did not depend on natural ice, it can be certain that many factory workers came to enjoy the products of the city’s numerous breweries that used ice not necessarily to serve cool products, but to be able to control fermentation temperatures during warmer months. Thomas Healy, Bottler & Brewer was located at Rockland and S. Main streets; Hurst’s Brewery, Brewer of Fine Ales and Porter was located on Columbia Street; and let’s not forget the flagship Old Colony Breweries Co. established in 1896.

Notwithstanding the city’s growing intemperance issues, the demand for ice was otherwise catalyzed by the ice needs of the Fall River and Providence Railroad and the Fall River Line steamships that sailed between Fall River and New York. To comprehend the ice needs of these floating palaces, it should suffice to consider the

…immense nightly travel by this line alone, when it is understood that to provision the [steamship] Commonwealth for a single trip, requires a ton of roasts, steaks and chops, two hundred pounds of poultry, two hundred loaves of bread, three hundred pounds of butter, two hundred and forty dozen eggs, one hundred gallons of milk, three hundred pounds of fresh fish, one hundred fifty pounds of salt fish, one hundred pounds of coffee, and other varieties of food in like proportion (Fall River 56).

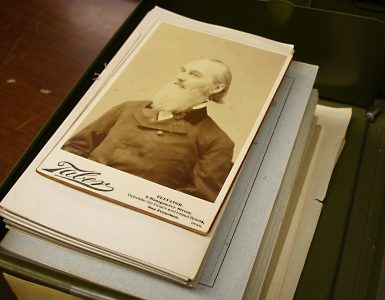

Cook and Durfee increased production, building a large addition on the New Boston ice house and establishing another ice house in Assonet. Other ice companies were formed including the South Pond Ice Company, the Crystal Company, the Fall River Ice Company, and the North Pond Ice Company. Perhaps tired of the growing competition, Robert Cook in 1879 sold his shares of the business to his partner William Durfee. Despite the competition, Durfee’s business and wealth grew as he came to be known fondly as “Ice Bill” throughout the city.

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

There was money to be made. A unique profitability of ice harvesting as a business was that no one person owned the ice on the pond (Cummings 17). This effectively meant that a company only needed a small parcel of land to access the pond, but then could feasibly harvest ice from anywhere on the pond’s surface. This circumstance led to intense and sometimes violent clashes between competing ice houses. The Fall River Evening News regularly reported on the progress of the ice harvest and documented the following state of affairs on February 4, 1899:

Certain ice houses of the Fall River Company and those of the Crystal Company are located on the same cove at North Watuppa and there is great rivalry as to which company shall harvest the ice in the cove. For years past this ice has practically been housed by the Fall River Company. This season the Crystal Company appearing as a new factor, it was expected that there might be more or less friction between the employees of the two. The expected happened Friday night. It is claimed by the men of the Crystal Company that the men of the opposition took possession of and harvested the ice which they had already marked out. For a time considerable hard feeling was evident between the men, and it threatened to end in an open rupture, which was, however, happily averted. Last Friday night, it is said that the men from the Fall River Company came across the cove and cut the ice from and in directly in front of the Crystal houses, which was used as a landing by the latter company. This ice was hauled away and housed; and the open water there now prevents, or, at least, greatly hinders the Crystal Company from housing their cut. This has not tended to dispel the feelings of rivalry between these two companies.

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Durfee managed to stay out of the fray and sold his business in 1901 to what was to become the Arctic Ice Company. At the time of the sale, Durfee’s company reportedly held 60,000 tons of ice (Fenner 240). In the years leading up to his death in 1901 at the age of 90, Durfee and the other ice companies were beginning to feel the pressure of the city’s newly formed Reservoir Commission that sought to protect the North Watuppa from contamination inasmuch as it was now the city’s primary drinking water supply. Ice harvesting was found objectionable given the live horses and the machinery used to harvest directly on the ice, and the city set up a rigorous monitoring process and used on-site inspectors to assure cleanliness in all harvesting operations:

The inspectors shall be present at all times when work upon the ice is in progress. No person shall spit upon the ice, nor defile it in any other manner . . . Each horse employed on the ice shall be inspected by the inspector of animals of the city of Fall River, and no horse suffering from glanders or other contagious disease, shall be permitted to work upon the ice of North Watuppa Pond. It shall also be the duty of the inspectors named under this rule, to see that droppings from horses or any other causes for defilement of the ice, are promptly removed (Silvia 552-553).

For all the city’s scrutiny and all the harvesting competition at the turn of the century, the natural ice industry was effectively over by the 1920s when commercial ice making and refrigeration were becoming well established. Many of the old ice houses, including the former Cook-Durfee (now Arctic Ice House) were simply used for storage. The last local natural ice deliveries were made by Nason Macomber’s ice house in Westport, which supplied the yet-to-be-electrified summer homes in Westport Harbor. His business was abruptly finished when the 1938 Hurricane destroyed the last remaining houses there that were still using ice boxes (Tamburello 2).

Several of the old ice houses burned. This too was the fate of the Cook-Durfee Ice House as well. The Fall River Herald News for Monday, March 27, 1933, documents that at approximately 8:00PM on the previous Saturday, a fire of undetermined origin broke out and quickly engulfed the four buildings in the ice house complex. Area residents jammed the nearby roadways to watch as the fire department pumped water from the pond to douse the one hundred foot flames and prevent the conflagration from spreading to nearby buildings and the Interlachen estate. While many may have suspected that the buildings and stored machinery (valued at $75,000) were burned for insurance, it was soon determined that the business was only minimally insured.

All buildings were lost and only the granite walls of the early 1864 ice house remained. By the year 1940, the city, in its continuing efforts to protect the North Watuppa, condemned and took possession of all of the land on the island. While other buildings on the island were demolished or moved, the city opted to allow the ice house walls to remain. It was too costly to tear down and remove the three foot thick granite walls. To this day the granite monument remains, a roadside testament to bygone days when ice was a crop, “Ice Bill” Durfee was the local king, and ice wagons traversed the city streets delivering ice to homes and businesses throughout Fall River.

Works Cited:

“Arctic Icehouses Destroyed by Fire.” Fall River Herald News 03/27/1933: 1.

Cummings, Richard O.. The American Ice Harvests: A Historical Study in Technology, 1800-1918. London: Cambridge University Press, 1949.

“Everybody Cutting Ice.” Fall River Evening News 00/04/1899: 7

Fall River, Massachusetts: A City of Opportunity. Fall River: B.R. Acornley & Company, 1911.

Fenner, Henry M.. History of Fall River. New York: F. T. Smiley Publishing Company, 1906.

Hall, Henry. The Ice Industry of the United States with a Brief Sketch Of Its History. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1888.

Report of the Watuppa Ponds and Quequechan River Commission. Boston: The Fort Hill Press, 1915.

Silvia, Jr., Philip T.. Victorian Vistas: Fall River 1901-1911. Fall River, Massachusetts: R. E. Smith Publishing Company, 1992.

Tamburello, Paul. “How Westporters Kept Their Cool.” Westport Shorelines 05/19/2005: Page 1.