by Michael Brimbau

First published in Spring, 2011, Volume 7, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

ONE CANNOT TALK OF THE SALOONS IN FALL RIVER WITHOUT GIVING MENTION TO DR. HENRY D. COGSWELL. COGSWELL, A DENTIST AND PHILANTHROPIST, WHO MADE HIS FORTUNE IN REAL ESTATE AND MINING IN CALIFORNIA DURING THE GOLD RUSH, WAS A ZEALOUS CRUSADER FOR THE TEMPERANCE MOVEMENT IN THE LATE 19TH CENTURY.

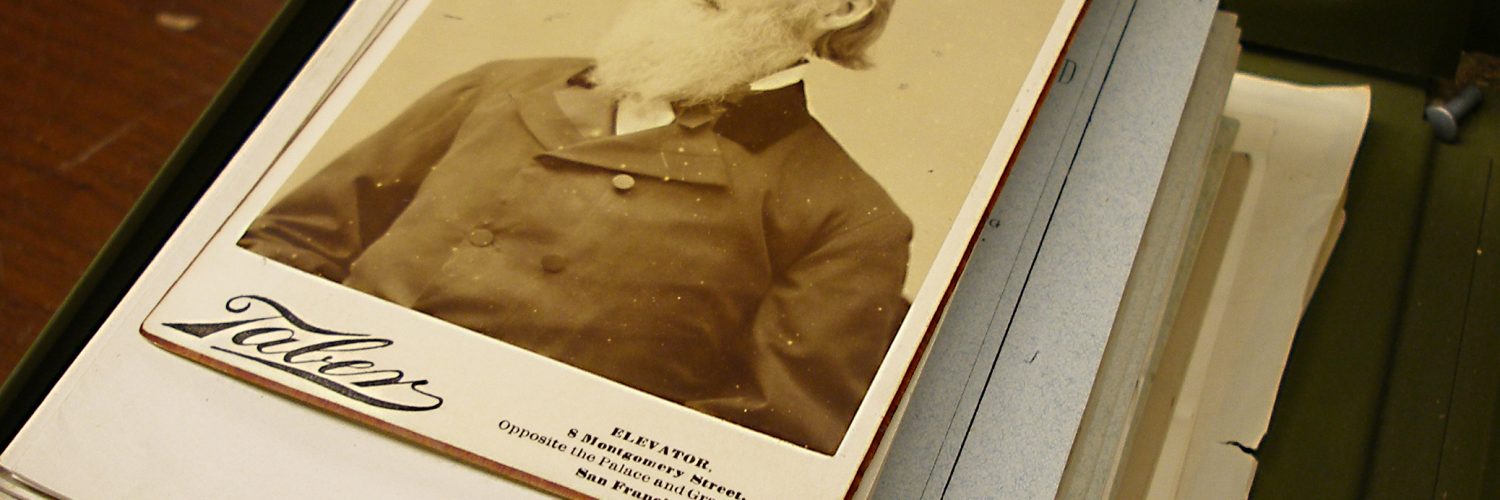

One cannot talk of the saloons in Fall River without giving mention to Dr. Henry D. Cogswell. Cogswell, a dentist and philanthropist, who made his fortune in real estate and mining in California during the gold rush, was a zealous crusader for the temperance movement in the late 19th century. He set out to install granite water fountains in the name of sobriety, while preaching the virtues of faith, hope, charity, and temperance. Cogswell lived in San Francisco, having moved there from the New England area where he was born in Tolland, Connecticut.

It is believed that most of the temperance fountains, if not all, were designed by Cogswell himself, and given freely as gifts to cities all over the country. His mission was to build and install one fountain for every 100 drinking saloons across the country. Ornate fountains, most displaying a life-sized statue of Cogswell himself, were installed in Washington D.C., Boston, Massachusetts, Rockville, Connecticut, Brooklyn, Buffalo, Rochester, New York City, New York, Dubuque, Iowa, San Jose, San Francisco, and Pacific Grove, California, Pawtucket, Rhode Island, and, of course, Fall River, Massachusetts.

The sober Cogswell must have been a bit of a naive optimist if he believed that the common citizen would abstain from hard drink to instead partake of the cool waters of one of his Gothic fountains. Could these fountains have been just a symbolic gesture on old Henry’s part, or a profound and virtuous attempt to curb the drinking of alcohol, brought about by an adoring devotion for his fellow man—or was there a more deep-seated bumptious motive, one which was self serving? All one needs to do is visit the massive and ornate Cogswell grave plot at Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland, California to arrive at your own conclusions.

Not all cities were willing to accept Cogswell’s gracious and costly offering. Historical newspaper accounts across the country are peppered with articles about how unwelcome some of the good doctor’s gifts were in many towns.

Rockville, Connecticut, was happy to receive its pillar of temperance, until the city’s denizens got a look at it. The fountain was topped with a statue of Cogswell himself, portraying him holding a glass of water in one hand and the Temperance vow in the other. It was not long before the rebellious natives of Rockville tore down the effigy in the dead of night, and threw it into a nearby lake. Later retrieved, it was placed back on the fountain, only to disappear a second time. Eventually, old Henry’s sculpture made its appearance for a third debut. This time it was placed in storage, until it was donated for the war effort, and melted down for its precious metal.

A similar fate befell the fountain given to Portsmouth, Ohio. After only a short five years, in 1899, the dispassionate citizens of Portsmouth, for reasons no one talks about (sip, sip), dismantled what they claimed was a distasteful and ugly landmark. The Portsmouth fountain was lost forever. Similar circumstances were repeated in Rochester, New York.

Complaints and dissatisfaction with Cogswell’s image in the late 19th century were many. Some claimed that they found the monument unsightly, while others were more truthful and took exception with what they felt was an attempt by Henry Cogswell to advertise himself by placing his image all over the country. As in Rockville, the image of Cogswell in Rochester, New York, disappeared overnight. Some, at the time, believed this was done with the city’s blessing, if not its muscle.

A fountain with a statue was also erected in Dubuque, Iowa, and met the same fate as those in Rockville and Rochester, but with a little twist. There, folklore recounts how vandals tore the statue of Cogswell off its fountain, sober or otherwise, and buried it under the soil where a new sidewalk was to be installed the next day. It was believed the statue was entombed under tons of cement. Years later, when the sidewalks were replaced, attempts were made to locate the statue, without success. It was concluded that it must have been dumped elsewhere after its kidnapping.

In Massachusetts, Cogswell’s gift to the city of Boston sat on the Common near West Street for a decade, before it also vanished. In San Francisco, three fountains were said to have been erected in that one city, even though none are believed to have survived to carry out Cogswell’s vision. The Chicago Daily Tribune reported that Dr. Cogswell offered that city a temperance fountain, but that the windy city rejected his generous donation.

To some city officials, it was just not worth the trouble. In California, one newspaper account stated that “The San Francisco Sphinx on Upper Market Space Must Go. Council Declares Him Unsightly and His Destiny Rests With Police Committee” (Daily Times, San Francisco, 3 Dec. 1896).

Similar accounts were reported in Rochester and Brooklyn, New York. The Brooklyn Eagle (10 April 1885) used such words as “hideous representation,” “horrid visage,” and “ghastly effigy,” to describe Cogswell’s fountains, calling Henry that “heartless Cogswell.” The paper goes on to declare that Henry Cogswell had claimed that the fountain was to be “topped with a statue of President Garfield, and not of himself,” and that he had lied, thus guilty of “hoodwinking the authorities and outraging the populace.” It was soon made clear that what these cities objected to was not so much the fountains themselves, but the image of Cogswell boldly standing on them.

Inquiries to the San Francisco Historical Society revealed that only one of Cogswell’s fountains have survived, but only in part, and not as a fountain. The granite used in the original fountain is now a pedestal for a statue of Benjamin Franklin in Washington Park, and was rededicated in 1979 as such. A cache was placed inside, to be opened in 2079. The pedestal is unrecognizable and all of its adornments have been removed. It now looks more like a cemetery marker than anything else.

It is believed that fifteen or sixteen fountains, most embellished with stone carvings and castings of birds, frogs, dolphins, and gargoyles, were actually commissioned. Not all were made of granite—some were a combination of granite and bronze, and at least one in Rockville, Connecticut, was made of zinc. One perfect example is the fountain in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, which is one of the most elegant of Cogswell’s designs, with its artistic and fragile bronze crane at its summit (some say a heron), perched on a granite plinth, resting over a school of granite fish.

The Cogswell fountain in Fall River is not as graceful as its Pawtucket sister, but similar still. Originally, the Fall River fountain was slated to be installed in Willimantic, Connecticut, in 1882, and the date 1882 is indeed inscribed in the fountain’s stone. After being rejected by that city, it ended up in the smoky mill town in Massachusetts, where it was seated at the northwest corner of City Hall. At the time of installation, a debate was held on whether the city would even accept the fountain. It was recorded in the Fall River Herald (25 Feb. 1971) that: “Cogswell’s gift wasn’t accepted without some bickering. Negotiations lasted two years. Many citizens disputed Cogswell’s right to the title of doctor. Consequently some felt the fountain was a medium of advertising for a ‘medicine man,’ as he had been described by some contemporaries.”

The fountain in Fall River, home of a thriving granite industry, was, ironically, made from New Hampshire granite. Fall River granite, though durable, does not polish well, and was probably rejected for that reason. The Fall River fountain was installed in the summer of 1884 on Market Street, just by the old City Hall, at a cost of $2500. The fountain soon earned a reputation for being unpopular with both fermented imbibers and tea sippers—having found little use for Henry Cogswell’s monument. The problem was that the water tank in the fountain was in need of ice in the summer to cool the water. At the time, the water that flowed from the fountain was described as being “luke warm and unfit to drink,” and filled with “nauseating fluid” (Fall River Daily Evening News, 17 July 1885). It appeared that the city was not willing to pay the $5 a week needed to fill the fountain with ice as strictly instructed by Cogswell. With all the taverns that must have existed in Fall River at the time, all this should have been but a minor inconvenience.

In 1962, Fall River’s City Hall was demolished to make way for a new highway. At that time, the 26-foot high fountain was dismantled and stored (dumped) at the city’s public works property on Rodman Street, where it deteriorated for the next ten years. According to the Herald News (9 Oct. 1971), when the new City Hall was constructed, the city’s shortsighted Mayor, Nicholas Mitchell, who felt the fountain held “no great practical value,” rejected the fountain. Thus, the Cogswell fountain sat abandoned on city property, where it was vandalized and damaged over time—still rejected once again. In time, it was determined that the dismantled fountain was just in the way. The keen idea given birth by city fathers was that perhaps the fountain should be “stored” at the city dump. Luckily, this never came to fruition, for if it had, the next step would have been to bury it, and it would have been lost forever.

Eventually, the fountain was rescued by the Fall River Historical Society and erected on its property in the fall of 1972, where it sat until plans were made in the later part of the 1970s to move it back to Main Street. Today, Henry Cogswell’s dry fountain sits less than a hundred feet from its original location, on the southwest corner of Central and Main Streets, across from City Hall.

It is believed that only five fountains survive today, in New York City, Rockville Connecticut, Washington, D.C., Fall River, Massachusetts, and Pawtucket, Rhode Island.