by Mary Elizabeth Naugle

First published in December/January, 2005, Volume 2, Issue 6, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

At the time of the Borden murders, the Portuguese of Fall River were just below the Irish in social pecking order. One thing we must credit Lizzie with is her resistance against the temptation to invent a swarthy mustachioed man fleeing the crime scene in a bloodied butcher’s apron. Of course, there were plenty of others to do it for her, and she did mention overhearing Father’s heated conversation with a foreign sounding gentleman, but an ethnic invention in the style of Susan Smart or the Runaway Bride was beneath her.

But this story is about the Portuguese, not Lizzie. Until recent years their contributions have gone without recognition, but now they are credited with revitalizing “an aging industrial city” with a renewed influx of immigrants. Ironically, they may be rebuilding what they first built. The reason? The Portuguese may have been the first European settlers in the region. The evidence? Three relics: a skeleton, a stone petroglyph, and a stone tower. I have written a poetic tribute to each, but must preface them with a brief explanation.

First, the long, lost skeleton, because it may have been that of the pilgrim himself and because it was ironically discovered by a Borden-by-birth: Hannah Borden Cook. One fine May morning in 1831, the thrifty Mrs. Cook had gone downshore for some sand with which to scour some knives (those Borden women always cared for their cutlery). Whilst doing so, the poor woman discovered a skull, soon to be followed by the rest of him, encased in bark and cloth. The skeleton, judged to be that of a young man, was in a fetal position and armed in brass breastplate with a quiver of brass arrows. Since the Native Americans were not known to have done any such metalwork, he was deemed to be some early European from Scandinavia or Troy. Longfellow recounted the Viking warrior’s story in a ballad, and the curious could gaze upon his remains at the Fall River Athenaeum until both Athenaeum and remains were consumed by the Great Fire a few years later. A brass fragment and contemporary drawings are all we have of him today, so very little can be concluded. I wish to stay entirely out of the ongoing dispute over the warrior’s identity. The Portuguese claim has the ring of artistic truth; for me that is enough. This claim is that the bones are those of Miguel Corte Real, a Portuguese explorer who went in search of his lost brother Gaspar in 1502. Like Gaspar, Miguel was never heard from again, but some believe he came to this country, was welcomed by natives and made a chieftain before his death. The armor would be of Portuguese origin, the burial, a respectful interment by Native Americans.

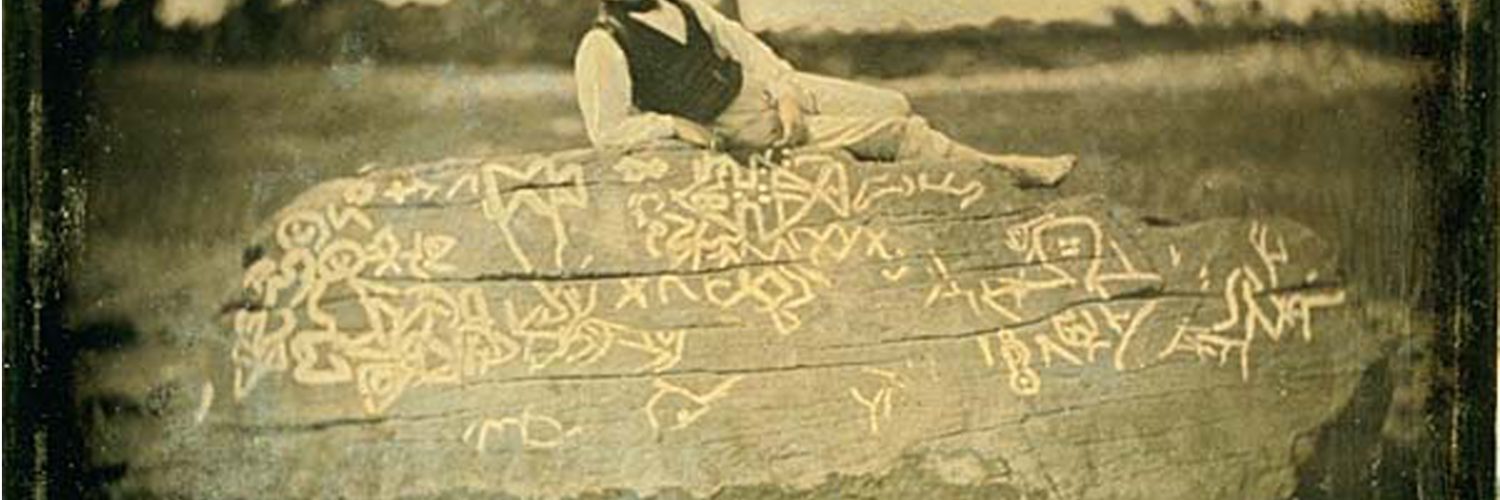

Second, the stone petroglyph known as Dighton Rock. Dighton Rock is a forty-ton boulder of sandstone, which lay until 1963 in a Taunton riverbed just outside Fall River. Before its removal, it was mostly under tidewater all but four hours a day. Now it can be seen at the Dighton Rock Museum, ten miles north of Fall River. The petroglyph was unquestionably here long before we were: drawings were made of its inscriptions by early settlers from Cotton Mather to Anne Hutchinson, but many have disputed over who put them there. The Portuguese theory varies from a name, date, and bio—Miguel Corte Real by will of God, here Chief of the Indians 1511–to a simple finding of the Portuguese Royal Coat of Arms and Cross of the Order of Christ. These last are the easiest to make out and to believe. The rock would help to identify Corte Real and place him on the shores of Fall River—and place him there long before the founding fathers of taunting Taunton ragamuffins.

Third, is the tower, or Old Stone Mill, of Newport, Rhode Island. This tower was owned by Gov. Benedict Arnold (not to be confused with the traitor of that name) until his death in 1678. Arnold’s will referred to “my stonebuilt-windmilln [sic].” That “my” leads some to believe Arnold built it; others dismiss the term as one indicating ownership only. Either way, the structure was used as a windmill in the eighteenth century, and who knows what else along the way. What makes the mill curious is its architecture—unique in the United States. The mill is an eight-arched cylinder, very like the Byzantine style that had been all the rage in the Spain and Portugal of Corte Real’s time. Longfellow was impressed enough with it to romanticize it as a monument to his Viking warrior’s lost love. But I prefer Portuguese theorists, who regard it a lookout tower for the third Corte Real brother.

And so ends a biased account of our three relics as a preface to three poems in their honor.

Works Cited:

Cahill, Robert Ellis. New England’s Ancient Mysteries. Salem, MA: Old Saltbox Publishing House, 1993.

Da Silva, Manuel Luciano. “Portuguese Tower of Newport.” Portuguese Pilgrims and Dighton Rock. Bristol, RI [s. n.]: 1971.

“Dighton Rock Retains its Aura of Mystery,” Fall River Herald News. 17 October 1978, A-10.

Dion, Marc Monroe. “Portugese a Great Force in Fall River,” Fall River Herald News. 26 February 2003, A19.

“Fire Didn’t Destroy Skeleton’s Legend,” Fall River Herald News. 17 October 1978, A6, with additional story “The Story Behind the Poem.”

Longfellow, Henry W. The Skeleton in Armor. Boston: J.R. Osgood, 1877.

Redwood Library and Athenaeum Finding Aid for the Old Stone Mill <redwoodlibrary.org/tower/millmenu.htm>.

“Skeleton in Armor Tale is Unsolved,” Fall River Herald News. 19 September 1953, A6.