by Mary Elizabeth Naugle

First published in February/March, 2006, Volume 3, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

If you defend Lizzie on the grounds that women simply do not do such things, this case will send you scurrying for backup. For the Papins are the Grandmemeres of Grand Guignol, whose weapons are the most terrifying of any ever used: their bare hands. Their story is one to read with the lights on—in fact, after their crime even they crouched in bed, lamp blazing.

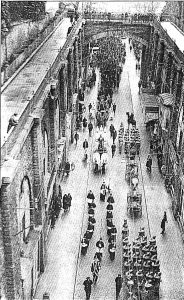

If on February 2, 1933, the groundhog retreated into his hole in the ground, it may not have been his shadow that sent him back to his Punxsutawney home. Something was surely in the air that day—if not in Pennsylvania, then in the sleepy town of Le Mans, France. That day two little maids went wild without so much as giving notice, and gouged and clobbered their mistresses to death on the first landing of their home.

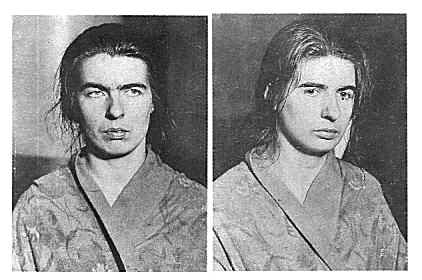

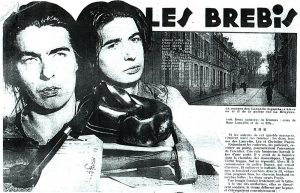

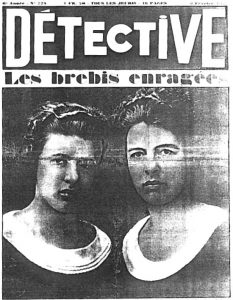

Here are the bare bones of the story. M. Lancelin, an inoffensive businessman of Le Mans, came home at 6:30, expecting to find his usually punctual wife and daughter ready to go out to a dinner engagement. To his dismay, he found the house in darkness, save for one garret room, which as glowed eerily as the room of Hitchcock’s Mother Bates. More disturbing was the fact that the doors were all bolted from the inside. M. Lancelin drummed up two policeman, whose names sound specially chosen for a clumsy allegory: Ragot and Verite, or “Morsel of Gossip” and “Truth.”1 What the two found upon breaking down the door was unprecedented in their own, or any other officers’, careers. The two women lay on the landing in their own gore—heads battered, calves slashed, undergarments ripped down, genitals smeared with each other’s blood. Most horrific of all, their eyes had been ripped from the sockets. Upon further investigation the officers found the occupants of that sinister upper room—sisters Christine and Lea Papin, aged 28 and 21—huddled together, wide-eyed, in the same bed. They went in their dressing gowns (those dressing gowns immortalized by photographs) to meet the magistrate, to whom they quite readily confessed. Here follows their startling confession. First, the older and more dominant, Christine:

When Madame came back to the house, I informed her that the iron was broken again and that I had not been able to iron. When I told her this, she had wanted to jump on me. At that moment, my sister and I and our two mistresses were on the first-floor landing. When I saw Madame Lancelin was going to jump on me, I leaped at her face and scratched her eyes out with my fingers. No, I made a mistake when I said I leaped on Madame Lancelin. It was on Mademoiselle Lancelin that I leaped and it was her eyes I scratched out. Meanwhile, my sister Lea had jumped on Madame Lancelin and scratched her eyes out in the same way. After we had done this, they lay and crouched down on the spot. I then rushed down to the kitchen to fetch a hammer and a knife. With these two instruments, my sister and I fell upon our two mistresses; we struck at the head with the knife, hacked at their bodies and legs and also struck with a pewter pot which was standing on a little table on the landing. We exchanged one instrument for another several times. By that I mean that I would pass the hammer over to my sister, so she could hit with it, while she handed me the knife, and we did the same with the pewter pot. The victims began to cry out but I don’t remember that they said anything. When we had done the job, I went to bolt the front door and I also shut the vestibule door. I shut these doors because I wanted the police to find out our crime before our master. My sister and I then went and washed our hands in the kitchen because they were covered with blood. We then went up to our room, took off all our clothes which were stained with blood, put on a dressing gown, shut the door of our room with a key and lay down in the same bed. That’s where you found us when you broke the door down. I have no regrets or, rather, I can’t tell you whether I have any or not. I’d rather have had the skin of my mistresses than that they should have had mine or my sisters. I did not plan any crime and didn’t feel any hatred towards them but I don’t put up with the sort of gesture that Madame Lancelin was making at me that evening.2

Lea’s initial confession was more laconic:

Like my sister, I affirm that we had not planned to kill our mistresses. The idea suddenly came to us when we heard Madame Lancelin scolding us. I don’t have any more regrets for the criminal act we have committed than my sister does. Like her, I would rather have had my mistresses’ skin that their having ours (96).

Lea would later embellish their motive as a response to continuous mistreatment:

Life with the Lancelins was hard. We never went out. Madame was haughty and distant. She only spoke to us when she wanted to scold us. She was always spying on us behind our backs and counting the lumps of sugar that remained in the basin. When housework was done in the morning, Madame Lancelin would put on white gloves and run her fingers over the furniture to see if the dusting had been done carefully and whether any speck of dust remained. If we had the misfortune to break the slightest thing, she at once took it out of our wages. It couldn’t go on. It had to come to an end. We were too unhappy (96).

Although Christine at first seemed to confirm this motive: “We’ve been servants for long enough. We’ve shown them our power” (96), she contradicted that motive before the trial, saying that she found her mistress’s strictness “quite right” (100). Significantly, she was also to say that she and Lea had been in “a black state of anger” and that if she “hadn’t been taken by surprise, things wouldn’t have gone so far” (101). The extent of the attack and the black state of anger seem inconsistent with the servant’s rebellion motive, convenient though that motive would seem to outspoken Paris intellectuals of the time.3 However, the Papins were not revolutionaries. In fact, they were undoubtedly quite as bourgeois as their employers. Why? Because Mme. and Mlle.’s scolding probably had very little to do with the murder. Instead, it seems far more likely that the sisters’ relationship prompted the attack. Lea’s statement that she and Christine never went out was quite true. However, the simple fact is that they did not want to. They had all they wanted in each other, and Mme. had begun to suspect it.

There is nothing new here. Quite early in the case, the defendants, particularly Christine, began to betray an unexpected aspect to their relationship. Christine’s mental state rapidly declined while in prison. She rambled to other inmates that she thought she must have been Lea’s husband in a former life. Next she began animal howling for her sister, sexual writhing upon the floor, even an attempt to claw out her own eyes when denied access to the girl—an attempt checked only by a straitjacket. Christine’s most bizarre and famous outburst came during the single visit permitted the two before the trial, when Christine tried to rip off Lea’s blouse while crying an anguished “Say yes to me! Say yes to me!”4 These displays of passion were unlikely to be ploys for an insanity plea. Christine seemed fully reconciled to the death penalty, and denied in court any sexual relationship: “There was nothing else between us” (106). Although her sentence was commuted to life, Christine was to live only until 1937, when she died of a lung infection brought on by a refusal to eat. After the trial, her obsession with Lea seems to have dwindled along with her desire to live. The one meeting she had with Lea after sentencing seems to have left Christine cold. Her only words were, “She is very nice, but she’s not my sister.”5 Lea, on the other hand, seemed to gain the personality her sister had lost, appealing her lenient sentence of ten years’ hard labor (given presumably because of her subsidiary role in the murders) and starting a new life when released for good behavior.

To return to the motive for the crime, however, the Papin sisters had clearly forged some kind of folie a deux (madness in pairs) that depended upon the exclusiveness of their relationship, and that relationship could suffer no intruders. Although many theorists have gotten considerable mileage out of the question of whether or not the sisters consummated their passion for one another, the question seems in the end to be moot. Christine’s cry of “Say yes!” should suffice to show that they were more than sisters. And yet she would deny it in court, while admitting to every other abomination imaginable. It would seem that there were some taboos even they could not own up to. Most likely, it was the discovery of those broken taboos that drove them to such excessive violence.

Jacques Lacan, the noted French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist, while analyzing the two at length for their homosexual sadomasochistic urges, seems to have accepted their version of the initial trigger, saying that “under anxiety of an imminent punishment” the Papins “mingled the mirage of their illness with the image of their mistresses”6—in other words, bashed their brains in. But how much did all this have to do with a blown fuse? Doubtless, the iron (returned just that day from the shop, having been repaired at Lea’s expense) did blow a fuse, but did Mme. or Mlle. really “jump on” either Christine or Lea? Neither showed any sign of such an attack. Yet, both mistresses were killed twenty times over. Had the girls found another occupation when an end was so suddenly brought to their ironing duty? And had the two employers (these women who were in Lea’s words “always spying on us behind our backs”), rushed upstairs to investigate? Christine said it would never have happened had she not been “taken by surprise.”7 These two lines may be the truest part of their stated motive. Mme. had been in such a hurry about something that she failed even to put their just-purchased meat into the icebox. Could it be that the mistresses had tiptoed up the stairs in order to surprise the mice at play? And was what they saw the real reason the two women never saw anything again? We can never know. But their insufferable roles as servants seem insufficient motive: upon release, Lea, under an assumed name, returned to work as a servant to the bourgeoisie. She was last traced in the year 2000 by documentarian Claude Ventura. At the time she was still living but, due to a stroke, unable to speak.8 She was interviewed, however, in 1966 by a sensational reporter from France-Soir.9 At that time, Lea was working under the name “Marie” as a maid for a luxury hotel. It was her particular duty to see that the knives were kept sharp and that all the cutlery was well accounted for.

Afterword

Some, like novelist and screenwriter Ed McBain, have suggested that something similar happened at 92 Second Street to prompt the murder, first of Abby, then of Andrew Borden. However there is very little to support the notion that Lizzie and Bridget were involved in some sort of sexual relationship and were discovered in bed together by a shocked Mrs. Borden. First, Lizzie never screamed out for Bridget like a bitch in heat while imprisoned in Taunton Jail. Second, it is very hard to imagine Lizzie and Bridget keeping a hatchet at the ready in case Abby returned early from her errand of mercy that August morning. Finally, it seems unlikely that Abby, upon stumbling upon such a scene, would have dashed to the guest room to crouch behind the bed. Instead, she would surely have run shrieking straight to Dr. Bowen’s house (as folks in that neighborhood always did). There was no sign of a struggle in any rooms but the crime scenes, and these signs involved no at-hand weapons—least of all, fingernails. Whatever Lizzie and Bridget might have been to one another, it is unlikely that they were indulging in a tryst that morning. That scene would not be played for another forty years.

Footnotes:

1 Rachel Edwards and Keith Reader, “Facts of the Case,” The Papin Sisters (UK: Oxford UP, 2001) 4.

2 Raymond Rudorff, “The Case of the Papin Sisters,” Classics in Murder: True Stories of Infamous Crime as Told by Famous Crime Writers, ed. Robert Meadley (NY: Ungar, 1986) 95-96.

3 The Papins became the darlings of Jean Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Jean Genet, and Jacques Lacan—poster girl victims of the bourgeoisie.

4 Rudorff, p. 99.

5 Edwards, 18.

6 Jacques Lacan, “Le Crime Des Soeurs Papin,” in Minotaure 1933, trans. at <http://lacan.com/papin.htm>.

7 Rudorff, p. 96, 101.

8 Neil Paton, “The Crime of the Papin Sisters: Works and Links Relating to the Papin Sisters,” 19 January 2006 <geocities.com/neil404bc/christin>.

9 Edwards, 19.

Special thanks to Neil Paton of http://www.geocities.com/neil404bc/christin.htm for permission to use his images to supplement this article.