by Mary Elizabeth Naugle

First published in August/September, 2006, Volume 3, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

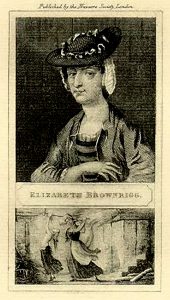

Elizabeth Brownrigg is proof that depraved and motiveless murder was not an invention of the twentieth century. She was tried at the Old Bailey on 9 September 1767, alongside her husband and a son, for the murder of fifteen-year-old Mary Clifford. She died alone, however, being the only one of the three found guilty. On reading her story, one can see why. Her accomplices, bad as they were, soon faded into the background as stagehands to a solo performance. She was one of a breed that preys upon the friendless—her descendants offer haven to and then abuse illegal aliens, for example—but she quickly graduated from simple neglect of her charges to mistreatment and torture, not from sheer bad temper but from genuine blood lust.

Elizabeth Brownrigg is proof that depraved and motiveless murder was not an invention of the twentieth century. She was tried at the Old Bailey on 9 September 1767, alongside her husband and a son, for the murder of fifteen-year-old Mary Clifford. She died alone, however, being the only one of the three found guilty. On reading her story, one can see why. Her accomplices, bad as they were, soon faded into the background as stagehands to a solo performance. She was one of a breed that preys upon the friendless—her descendants offer haven to and then abuse illegal aliens, for example—but she quickly graduated from simple neglect of her charges to mistreatment and torture, not from sheer bad temper but from genuine blood lust.

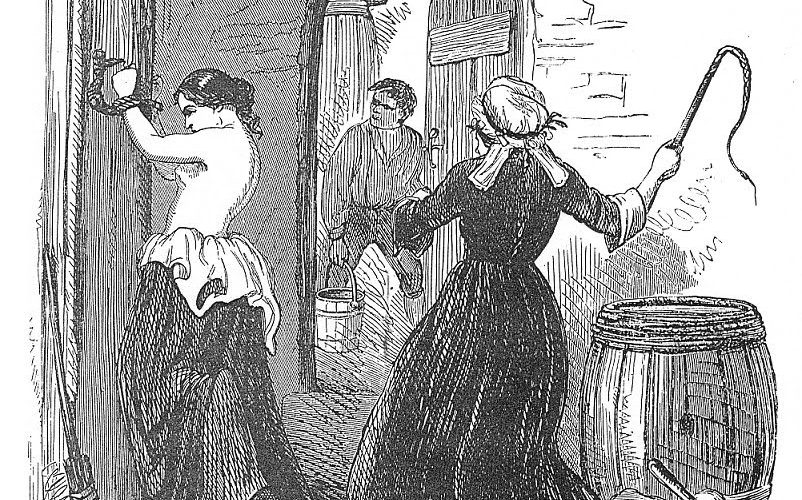

Brownrigg’s primary weapon was a horsewhip, but she occasionally made do with a hearth-broom, and she embroidered upon simple beatings by depriving her victim of food or clothing and by keeping her chained by the neck for days at a time. Sadly enough, others were likewise brought to court for the same thing, for instance Metyard and Branch, but Brownrigg’s case is the best documented: it can be found not only in The Newgate Calendar but also in the Old Bailey Proceedings. We not only have some contemporary background on the case beyond the unreliable sensational broadsides sold in the streets on execution days, but we have the transcripts of the trial itself.

According to the Newgate Calendar, James Brownrigg was a plumber at Flower-de-Luce Court in Fleet Street (home of the Demon Barber), London. Elizabeth, his remarkably prolific spouse—being the mother of sixteen—traded upon that vast experience by assuming the profession of midwifery. In addition to boarding ladies in waiting during their confinement, Elizabeth also made house calls and was soon appointed ministering angel to the St. Dunstan’s parish workhouse. By the time our history begins, her own sixteen had dwindled to two: a son, John, who stood trial at her side and a younger, seldom mentioned, lad named Billy. Elizabeth’s trade being brisk, she decided to avail herself of the cheap labor readily available from the workhouses and foundling hospitals of London. These girls, all in their early teens, would be taken “upon liking” (akin to taking for a test spin), before the girl should be “bound” (a sadly apt term here), an agreement whose advantages were all on the side of the employer.

Mistress Brownrigg took a total of three Marys into servitude. The Calendar claims she had other girls before them, but their names and fates go unrecorded. Mrs. Brownrigg’s pattern was to care for her girls well until they were bound—a month or two—then introduce them to the hard realities of life. The first of the Marys, Mary Mitchel, lived to testify at the Brownrigg trial. The second, Mary Jones, seized her opportunity to flee one night when the Brownriggs carelessly left the key in the house door. Having just suffered the pain and indignity of being beaten while stretched across two kitchen chairs, Mary Jones felt no compunction about seeking aid from the foundling hospital from which she had recently been taken. The surgeon there found her injuries to be so savage that the governors of the hospital directed their solicitor to send James Brownrigg a strongly worded letter. Although that letter threatened prosecution if no justification of such treatment should be provided (just what might be considered justification is a matter for conjecture), when Brownrigg failed to reply, the hospital saw fit to let the matter go. Mary Jones, at least, was given an honorable discharge from her servitude, and so passes from history. Mary Mitchel was not so lucky. After what must have been a very long year of similar treatment, she attempted to repeat the escape of her fellow worker, but she was discovered and returned to the bosom of the Brownrigg family by young Billy. We are not told, but can imagine, the sort of punishment Mary Mitchel received for that failed mutiny.

Unluckiest of all, though, was Mary Clifford. Mary Clifford was bound over by the overseers of Whitefriars’ poor. Like Mary Mitchel, Mary Clifford (soon dubbed Nanny by the Brownriggs to avoid confusion) was treated in acceptable fashion until she was bound over, at which time her mistress began to show her true colors. The first sign of the change in wind was Mary Clifford’s removal from her bed as punishment for what the Calendar calls a ”natural infirmity.” The trial reveals the specifics:

Unluckiest of all, though, was Mary Clifford. Mary Clifford was bound over by the overseers of Whitefriars’ poor. Like Mary Mitchel, Mary Clifford (soon dubbed Nanny by the Brownriggs to avoid confusion) was treated in acceptable fashion until she was bound over, at which time her mistress began to show her true colors. The first sign of the change in wind was Mary Clifford’s removal from her bed as punishment for what the Calendar calls a ”natural infirmity.” The trial reveals the specifics:

Q. Where did she lie after she was bound apprentice?

M. Mitchel. Sometimes on the boards in the parlour, sometimes in the passage, and very often down in the cellar.

Q. How came she to lie there?

M. Mitchel. She had the misfortune of wetting the bed; that was the reason of her being moved; at first she had a mat to lie on.

Q. Had she any thing to cover her?

M. Mitchel. Sometimes she had her own clothes, and sometimes a bit of a blanket.

The girl was soon to be denied such luxuries, however. After all, she had the cheek to expect victuals in addition to bedding, and when she attempted to remedy hunger by stealth, Mrs. Brownrigg quickly showed her what such impertinence should lead to. For although, like Mother Hubbard, Mary Clifford found the cupboard bare, she had the double misfortune of breaking the cupboard in her search for food. Injustice was swifter than justice ever dreamed of being. Mistress Brownrigg armed herself with a riding whip with which she beat Mary Clifford about the head and shoulders with the stump end of the whip:

Q. What was done to her upon this?

M. Mitchel. My mistress made her strip naked to wash, and beat her all the while at times.

Q. How long was she washing naked?

M. Mitchel. She was naked washing all the day.

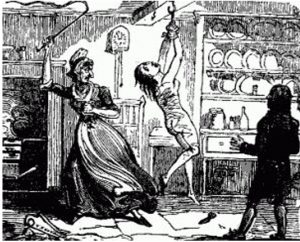

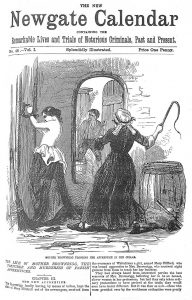

Perhaps Mistress Brownrigg was able to justify these extremities to herself by the argument that she was rightly taking out the cost of repairing the bare cupboard upon Mary Clifford’s bare hide, but one hopes that the parish would not, had it been informed. The parish was not informed, and Mrs. Brownrigg continued to indulge a passion that went beyond simple cruelty to perversion. To strip the girl down for the beating, to renew that beating whenever the whim struck her, and to keep her charge naked for the resumption of her duties at the washtub—these were not acts of punishment or of rage, but acts of vicious pleasure. This assumption is supported by the following line of questioning concerning the nakedness that was to become the norm for Mary Clifford’s beatings, which by this point in the narrative had been embellished by means of a rope tying the girl to a water pipe that ran along the ceiling:

Perhaps Mistress Brownrigg was able to justify these extremities to herself by the argument that she was rightly taking out the cost of repairing the bare cupboard upon Mary Clifford’s bare hide, but one hopes that the parish would not, had it been informed. The parish was not informed, and Mrs. Brownrigg continued to indulge a passion that went beyond simple cruelty to perversion. To strip the girl down for the beating, to renew that beating whenever the whim struck her, and to keep her charge naked for the resumption of her duties at the washtub—these were not acts of punishment or of rage, but acts of vicious pleasure. This assumption is supported by the following line of questioning concerning the nakedness that was to become the norm for Mary Clifford’s beatings, which by this point in the narrative had been embellished by means of a rope tying the girl to a water pipe that ran along the ceiling:

Q. Had she used to have her clothes on when your mistress tied her up in this manner to beat her?

M. Mitchel. No, no clothes at all.

Q. How came that?

M. Mitchel. It was my mistress’s pleasure that she should take her clothes off.

All this as consequence of a single pathetic attempt at presumed defiance more appropriately termed an attempt at self-preservation. According to the Newgate Calendar, the zeal of these beatings eventually broke the water pipe—a detail not mentioned at trial, but which would provide a likely explanation for her requisition of a hook to be installed in the kitchen beam by her husband:

Q. How long is that ago, since they talked about putting up the hook?

M. Mitchel. I believe it is about three months ago.

. . .

Q. How was it fastened up?

M. Mitchel. There was a screw went into the beam, and the part the rope went into was like a ring.

Q. After it was up, what use was made of it?

M. Mitchel. No other than to tie us both up.

. . .

M. Mitchel. No body made use of it but my mistress; we were tied with our hands over our heads, and the rope went through the ring.

Q. How was she dressed when tied up?

M. Mitchel. She was never dressed when tied up; she never was tied up but when she was quite naked.

Q. By what part was she tied?

M. Mitchel. She was only tied by her hands; she was always beat till she bled.

Q. Was she often tied up to that hook?

M. Mitchel. She was very often.

Q. How often?

M. Mitchel. About once a week.

Her mistress’s pleasure extended beyond her waking hours, for bad as they had been before, Mary Clifford’s sleeping arrangements were made even more unbearable. She was now put to bed in a coal hole under the cellar stairs. As if compelled to outdo herself, her mistress began to leave her and Mary Mitchel there for whole weekends while she and the family repaired to their country home:

Her mistress’s pleasure extended beyond her waking hours, for bad as they had been before, Mary Clifford’s sleeping arrangements were made even more unbearable. She was now put to bed in a coal hole under the cellar stairs. As if compelled to outdo herself, her mistress began to leave her and Mary Mitchel there for whole weekends while she and the family repaired to their country home:

Q. How often may they have gone into the country on a Saturday, and staid till Sunday night?

M. Mitchel. I believe they may six or seven times.

Q. Had you any bed to lie on in that place?

M. Mitchel. No, we used to get some rags out of the fore-garret, and sometimes we had used to put our own clothes on; sometimes we had only a boy’s waistcoat; my mistress used to order us to take off our clothes.

. . .

Q. When did you use to be let out?

M. Mitchel. On the Sunday night.

Q. What victuals had you to eat the time you were in?

M. Mitchel. A piece of bread, nothing but bread.

Q. Had you any thing to drink?

M. Mitchel. No.

Q. Did you not ask for water?

M. Mitchel. No, we were not a-dry when we were put in.

Q. Were you never a dry when you were there?

M. Mitchel. Yes, we were.

In fact, one night Mary Clifford grew dry enough to risk detection and its sure consequences in a search of water. Those consequences were swift and sure:

Q. Do you know any thing of a jack-chain?

M. Mitchel. I do; Mary Clifford was fastened to it; one part of it was put round her neck, and the other fastened to the yard-door.

Q. Was it done very tight?

M. Mitchel. I believe it was as tight as it could be round her neck, without choaking her.

. . .

. . . she was to scour the copper, and was chained to the yard-door all day, and loosed from the door on nights, just before dark, but sent down into the cellar with her hands tied behind her, with the chain on her neck.

. . .

I saw it put about her neck, but cannot tell by whom; there were my mistress, and the youngest son, and my master by, when it was put about her neck; to the best of my knowledge, it was my master’s youngest son Billy, that called her up by my mistress’s order. I heard her beat her; there was a brass chain, a squirrel chain, added to the iron chain, to make it longer.

. . .

Q. Which part of it was about her neck?

M. Mitchel. It was the iron part.

Mary Clifford must have had a strong constitution, for remarkably enough she continued in fairly good health until Friday, July 31st, when her mistress returned in a particularly ill temper from a lengthy lying-in:

M. Mitchel. She was in a very pretty good state of health, only her head and shoulders were sore, they were scabbed over; there were very great scabs on each shoulder, and three or four on the head; them on the head were in a fair way to get well.

. . .

Q. On that Friday morning what did Mrs. Brownrigg do?

M. Mitchel. About ten in the morning, after she had done breakfast, she went down in the kitchen, and tied Mary Clifford up to the screw-hook, and said she would make her remember to work when she was out.

. . .

. . . as she came home, she took and tied Mary Clifford’s hands, and fastened the rope to them, and put that thro’ the hook; this was about ten o’clock, I was in the kitchen at the time, there was no body there but us three; she horse-whipped her very much all over her, there were drops of blood under her as she stood, she struck her with the lash when she let her down as she was at her washing, and with the butt-end of the whip over the head, as she was stooping at the tub, and complained she did not work fast enough.

. . .

. . . to the best of my knowledge I saw her tied up five times that day, and whipped by my mistress . . .

. . .

Q. Did she do any work about the house on the Sunday?

M. Mitchel. Yes, she was about just to sweep the room, and clean the sink in the back-parlour.

Q. Where were the family then?

M. Mitchel. I think, to the best of my knowledge, the family was all then in the back-parlour; to the best of my knowledge, my master, and John, and my mistress were there.

Q. How was the girl dressed?

M. Mitchel. She then had a boy’s waistcoat on till the afternoon; I do not recollect she had any thing on her head, that was very bad then; the waistcoat was put on when she was bad [‘bad’ presumably means raw and/or bloody], to go in to clean the room before dinner; that was between breakfast and dinner; she went about the room naked before the waistcoat was put on; her shoulders were in a very raw condition.

Q. Did no body take notice of the condition her head and shoulders were in?

M. Mitchel. No, not as I know of.

Even the hardiest constitution has its limits, and Mary Clifford’s seems to have reached its limit that day. Her decline was so rapid that even her mistress became alarmed, even to the point of turning her nursing skills to her victim. Mrs. Brownrigg began applying poultices made of bread and hot water to Mary Clifford’s swollen neck. These proved to be too little too late, however, and the girl’s condition merely worsened. Rather than risk prosecution by taking her to hospital, the family conspired to hide the girl away. Their choice of hiding place proved unfortunate for them, for they placed her in the open courtyard, where concerned neighbors soon observed her. On August 3rd, the baker next door sent Clipson, his apprentice, to climb out the window to attempt to speak to the girl. The young man described the encounter thus:

Even the hardiest constitution has its limits, and Mary Clifford’s seems to have reached its limit that day. Her decline was so rapid that even her mistress became alarmed, even to the point of turning her nursing skills to her victim. Mrs. Brownrigg began applying poultices made of bread and hot water to Mary Clifford’s swollen neck. These proved to be too little too late, however, and the girl’s condition merely worsened. Rather than risk prosecution by taking her to hospital, the family conspired to hide the girl away. Their choice of hiding place proved unfortunate for them, for they placed her in the open courtyard, where concerned neighbors soon observed her. On August 3rd, the baker next door sent Clipson, his apprentice, to climb out the window to attempt to speak to the girl. The young man described the encounter thus:

. . . I saw through that down into the yard; there I saw Mary Clifford, her back and shoulders were cut in a very shocking manner, and likewise her head; I observed her hair was red, she had no cap on, I saw blood and wounds on her head.

Q. Did you know her before?

Clipson. I had never seen her before as I know of; then I went down to the one pair of stairs, and crawled out at a window upon the leads; I crept on my belly to the sky-light, and laid myself cross it; I looked down, there I had a full view of her; I spoke to her two or three times, but could get no answer; I tossed down two or three pieces of mortar, and the third piece fell upon her head; then she looked up in my face, I saw her eyes black, and her face very much swelled; she made a noise something like a long Oh; and then drew herself backwards; I heard Mrs. Brownrigg speak to her in a very sharp manner, and asked what was the matter with her.

On the strength of Clipson’s distressing account, the baker’s wife conferred with the watchmaker’s wife from across the street and sent for the fourth and final Mary of the case: Mary Clifford’s stepmother (referred to as mother-in-law at trial and, confusingly, as Mary Clifford in testimony). Mary Sr. had tried to see her stepdaughter twice in the past two months but had been told she was no longer there. This time she brought the parish officers and Clipson as witness. Even during this age when cruelty was the norm, the Brownriggs realized that Mary Clifford’s condition was beyond the pale and that they could expect harsh judgment at law if discovered. They, therefore, determined to brazen it out. Here is a direct transcription of Clipson’s account of the confrontation:

On the strength of Clipson’s distressing account, the baker’s wife conferred with the watchmaker’s wife from across the street and sent for the fourth and final Mary of the case: Mary Clifford’s stepmother (referred to as mother-in-law at trial and, confusingly, as Mary Clifford in testimony). Mary Sr. had tried to see her stepdaughter twice in the past two months but had been told she was no longer there. This time she brought the parish officers and Clipson as witness. Even during this age when cruelty was the norm, the Brownriggs realized that Mary Clifford’s condition was beyond the pale and that they could expect harsh judgment at law if discovered. They, therefore, determined to brazen it out. Here is a direct transcription of Clipson’s account of the confrontation:

. . . we told [Mary Sr.] what I had seen, and what a condition the girl was in; she cried and went the next day to the overseers of the parish; they came on Tuesday the 4th with her; they went into the house; James, the father, said the girl was at Stanstead in Hertfordshire, and had been there a fortnight; I went in, and said I would take my oath I saw her the day before, which was the third; he said, she was looking after his daughter that had the hooping cough; I said, according to the description Mrs. Clifford gave of her, I believed it was she, and that she was in a very deplorable, bloody and shocking condition, with several wounds upon her; he swore by G – d she was not in the house; when Mr. Grundy [a parish officer] insisted upon seeing the girl, I just saw Mrs. Brownrigg; she turned about, and shut the door, and went off; we were in the house about half an hour, arguing with Mr. Brownrigg; he produced Mary Mitchel, and said, by G – d, that was all the girls he had in his house; our maid. was standing at the door; she went in and said to Mary Mitchel, what is the matter with your cap; she pulled off her cap and handkerchief; then I said I would take my oath that was not the girl that I saw, for the other girl was worse than the, a great deal, both on her head and back, as far as I could see; (I could see her shoulders, and near half way down her back when she stooped;) besides, the other girl had red hair cut short. When Mr. Grundy saw Mary Mitchel, he said, is this usage! and took the girl out into the court; Mr. Brownrigg then desired he would not expose him; then Mr. Grundy sent for Mr. Hughes, the constable, from Brown’s coffee-house; when he came, we searched the house from top to bottom; and could not find the girl in the house; we searched every, where, where we thought any body possibly could be; the key of the garret could not be found, and Mr. Brownrigg broke that door open for us to search there; then they took Mary Mitchel away to the workhouse; in about half an hour after they came back again, and searched the house again, and could not find her; then they called a coach to take Mr. Brownrigg to the Compter; he then, when he found he must go, gave the coachman a shilling, and said he would produce the girl; I was then standing at the door, presently the girl was brought.

To the last, the Brownriggs seemed to nurture some mad hope that they could escape detection. James stalled as long as he could before producing poor Mary Clifford—even serving a round of wine to the parish officers, who were not themselves above accepting. Her rescuers do not seem to have been in a particular hurry. In fact, their leisurely methods are worth recording here. In the words of Elsdale, another parish officer,

I then asked if he was ready to go [to prison for failure to account for Mary Clifford’s whereabouts]; then he said we might come into that room; he said he would agree to produce the girl, provided that would satisfy us; I told him we should be satisfied, provided he would produce the girl, and asked him how long he would be before he would produce her, because he had told us, she was at Stanstead in Hertfordshire, and had been there a fortnight; he brought out a bottle of red wine, and handed round a glass a piece for us to drink, and, I think, in about half an hour after he said he would produce her; she was led in by a tallish young man, about such another as the son at the bar, but I cannot swear it was he, not taking much notice of his person; I went up to the girl, and asked her how she did; she could not speak, her mouth was extended; she could not shut her lips, her face was very much swelled; I thought the best method I could do, was to take her away to the workhouse; there was a surgeon came; he said she was in very great danger.

Q. Was the prisoner in the room all the time till the child was produced?

Elsdale. He was the greatest part of the time, if not all the time; he only went into another room for the bottle of wine.

Either the officers’ patience was unparalleled or the Brownrigg wine was exceptional. Although the loss of time probably made no difference to Mary Clifford’s fate—the extent of her injuries and resulting infection were too far advanced to reverse—the indifference of the parish officers is as chilling as in the case of Mary Jones. Nearly 150 years before the Borden case, August 4 was made infamous. Mary Clifford and Mary Mitchel were rescued that day, but Mary Clifford did not escape the sufferings of this realm until the 9th.

Mary Mitchel was probably the first in history to welcome the sight of the workhouse to which she was delivered. Although she too was in a frightful condition, she recovered from her wounds and lived to testify against her employers. After that trial, she disappears. We can only hope that her remaining years made up for those spent with the Brownriggs.

James’s plea bargain was quickly forgotten when the officers saw the condition of Mary Clifford. He was swiftly transported to prison to await trial, having first charged his apprentice to remove the hook from the kitchen beam and to burn all sticks and other evidence. With their usual efficiency, the officers allowed the chief culprit, Elizabeth, to escape with son John. Billy was presumably left to fend for himself. Although the two disguised themselves in rags, they were discovered on August 15th, when the chandler with whom they had taken lodgings recognized the pair from their newspaper descriptions. He notified the constable, who was pleased to convey the two to prison.

James and John were certainly not blameless in the case. According to Mary Mitchel, James had beaten Mary Clifford once with an old hearth broom. John, likewise, had beaten the girl on two occasions: once with the buckle end of a belt, and once finishing the job his mother had begun at her usual station in the kitchen. They had furthermore been clear accessories to Elizabeth’s brutality and to an attempted cover-up of the crime. Their lack of further involvement may indicate no more than a lack of initiative. Most likely, they were merely social brutes, unlike the lady wife. The two, though found Not Guilty of murder, were both sentenced to six months in prison as accessories. Still, in an age that could hang men for theft, that penalty seems exceedingly light.

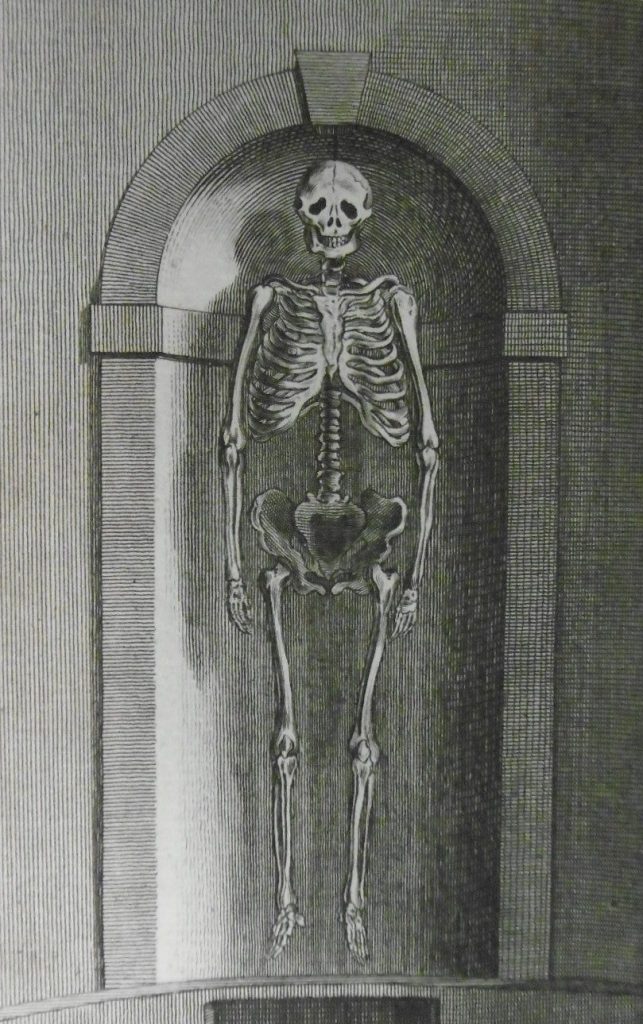

As for Elizabeth Brownrigg herself, the punishment suited her crime admirably. She was hanged for murder, then dissected, “anatomized,” and displayed at Surgeon’s Hall. She would hang there fully exposed for many a year, in much the same way as Mary Clifford had hung helpless and naked in the Brownrigg kitchen.

Works Cited:

“Elizabeth Brownrigg”. The Complete Newgate Calendar, Volume IV. 6 November 2003. Tarlton Law Library, University of Texas at Austin. 15 July 2006. <http://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/lpop/etext/newgate4/brownrig.htm>

The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, London 1674 to 1834. 2005. The Old Bailey Proceedings Online. 15 July 2006. <http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/facsimiles/1760s/176709090002.html>