by Mary Elizabeth Naugle

First published in February/March, 2007, Volume 4, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

There is a second handle-less hatchet under glass in Massachusetts. Like the exhibit from the Borden trial, this one is associated with bloodshed. Like it, this one is further associated with a woman. Unlike the hatchet in Fall River, the question of provenance lies only in whether this hatchet head is the right one. For this woman, Hannah Dustin, proudly took credit for her actions, while Lizzie Borden maintained her innocence to the end. Lizzie, although exonerated, would remain notorious; Hannah, on the other hand, though responsible for five times the death toll of the Bordens would be celebrated in legend and in stone. She had, after all, struck back at enemy marauders. In 1861, she became the first American woman to be honored with a statue, which was begun that year in Haverhill, Massachusetts. The honor was to be repeated in Penacook, New Hampshire in the 1870s. Hannah’s story inspired generations of schoolchildren. Until now. Of late, she has been vilified. The Abenaki Nation claims that the legend distorts the truth of the story, promoting violence and racism. What once was deemed an act of valor is now called an atrocity. Haverhill is divided between traditional pride and new found shame over their ancestress. And many ask whether she was a “Joan of Arc or Lizzie Borden.”

This is a question that cannot be answered with a sound bite. Before even attempting an answer, we need to know her story. Her actions were shaped by a particular place and time. Her story is no more abstract than any personal history, and that history was not only concrete but also extreme and harrowing. Many of the facts surrounding Hannah’s 15 days of fame are blurred by the passage of time. The names and roles of her fellow captives vary slightly from one account to another. Even her own last name is spelled both “Dustin” and “Duston,” even “Dustan.” Her descendants seem to prefer “Duston,” but the New Hampshire monuments and markers use “Dustin,” and so will I. Further, the dates are frequently inconsistent—even within the same sources. Hannah never recorded her own story. She told it to Cotton Mather and to Samuel Sewall. Mather wrote a full account in his Magnalia Christi Americana. Sewall tells a portion of it in his diary. The rest is oral history gathered by the likes of John Greenleaf Whittier and Dustin descendants. Notably missing is a contemporary account from the other side. Still, I believe that with perseverance, we can find enough common threads among surviving accounts to piece together the essence of the truth. Here it is, to the best of my knowledge.

Hannah’s odyssey began on March 15, 1697. She had just given birth to her twelfth child, Martha, six days before. Seven older children were scattered nearby, at work or play, ranging in age from seventeen-year-old Hannah to an unnamed toddler. The other four children had died young. Hannah and Martha were both resting comfortably, with the help of a woman named Mary Neff, a woman variously referred to as servant, neighbor, or nurse. Most likely she was the latter two and undoubtedly friend, as well. Suddenly an unnumbered band of Indians burst upon the scene on the outskirts of Haverhill. Hannah’s husband, Thomas, tried to take mother and child from the house to the safety of the garrison, but their movements were slow, and Hannah begged him to save what older children he could instead. She then entrusted Martha to Mary Neff. Thomas was better than his word. Rather than scoop up one or two upon his horse and flee, he dismounted, using his horse as a shield, and gathered all the children to safety, while keeping his musket trained upon the enemy. Once the dust cleared, 27 villagers lay dead, 13 were taken captive. Among the captives were Hannah Dustin, Mary Neff and baby Martha.

Hannah’s odyssey began on March 15, 1697. She had just given birth to her twelfth child, Martha, six days before. Seven older children were scattered nearby, at work or play, ranging in age from seventeen-year-old Hannah to an unnamed toddler. The other four children had died young. Hannah and Martha were both resting comfortably, with the help of a woman named Mary Neff, a woman variously referred to as servant, neighbor, or nurse. Most likely she was the latter two and undoubtedly friend, as well. Suddenly an unnumbered band of Indians burst upon the scene on the outskirts of Haverhill. Hannah’s husband, Thomas, tried to take mother and child from the house to the safety of the garrison, but their movements were slow, and Hannah begged him to save what older children he could instead. She then entrusted Martha to Mary Neff. Thomas was better than his word. Rather than scoop up one or two upon his horse and flee, he dismounted, using his horse as a shield, and gathered all the children to safety, while keeping his musket trained upon the enemy. Once the dust cleared, 27 villagers lay dead, 13 were taken captive. Among the captives were Hannah Dustin, Mary Neff and baby Martha.

First, their attackers had ransacked the house, breaking the china and snatching the cloth from the loom. Then they set fire to the home, along with five other houses in the village. According to family tradition, Hannah was given so little time to leave her bed that she had only one shoe and not so much as a shawl to protect her from a harsh March wind. Thus clad, she set out in the cold to make a cross country trek of over one hundred miles—twelve on that first night. She and Mary must have been terrified for their families, but in addition to their fears, they had an immediate sorrow and horror. According to some, Martha’s crying annoyed her captors. Others say that they thought she slowed down the party too much. In any case, Martha was taken by the heels and dashed against a tree. Like Andromache of Troy, Hannah could only watch in horror. She and Mary dared not cry openly, nor could they pray before their disapproving captors, who had been converted by the French and now said their prayers in Latin.

The party made its way overland to the north, trudging through snow and mud along the way. March is often cruel in this region; that March was particularly so. The intended destination was Canada, where the captives would command a good price from the French. Hannah and Mary were taunted with tales of how they would be made to run the gauntlet naked and serve as targets in tomahawk throws. Sometime between the 15th and the 30th of March, they reached an encampment near Penacook on an island where the Contoocook meets the Merrimack. It was here that the large party split up. Some continued upstream. Hannah and Mary were taken to an Indian camp on the island, where they were placed with its leader, Bampico, one other warrior, three woman, seven children, and one white boy. It is unclear whether the island inhabitants had been part of the earlier raid or whether they were merely to provide escort to Canada. Representatives of the Abenaki Nation now claim that the islanders would have been a peaceful group, who meant to welcome the newcomers into their family. However, they were to be family only until they reached Canada. There, all family ties would be severed, and the captives would be sold. Even on the island near Penacook, Hannah referred to Bampico as her master. The term was not one she would have used for family, nor could she anticipate a promising future. To their credit, the group had adopted the white fourteen-year-old boy, Samuel Leonardson, some eighteen months before, and until he saw the two new arrivals, Samuel had been happy and inclined to remain. Still, it seems likely that, despite Leonardson’s good treatment by the family, the two women were distrustful and terrified. If an innocent baby could be killed on the grounds of inconvenience, what could they expect? They are unlikely to have expected any more mercy here than on the trail. Leonardson, upon meeting the women (and perhaps hearing of the atrocities in Haverhill), soon threw in his lot with theirs. The three, with Hannah as their leader, planned to escape.

On March 29th, Leonardson asked Bampico how braves were able to kill and scalp their victims. Bampico readily instructed him, a response that shows that Bampico trusted the boy, but also that he was not innocent of the ways of violence. Neither would be the three captives in less than 24 hours.

According to her detractors, Hannah Dustin made her captors drunk or drugged them with herbs found on the island, then treacherously killed them in their stupor. I find it unlikely that she would have found any obliging opiates growing on the small island (doubtless made smaller by flooding) even in late March. As for liquor, who knows? We have no autopsy details on the condition of the victims before death. Regardless, by the statements of Dustin, Neff, and Leonardson, the three struck when their victims were sleeping. Tradition, kept alive by the inscription at the base of the statue on the island, has it that they struck at midnight. The time is undoubtedly romance, though. They had no clock by their sides. The three were able to disarm the victims, and, at a signal from Hannah, strike them in the manner Bampico had recommended.

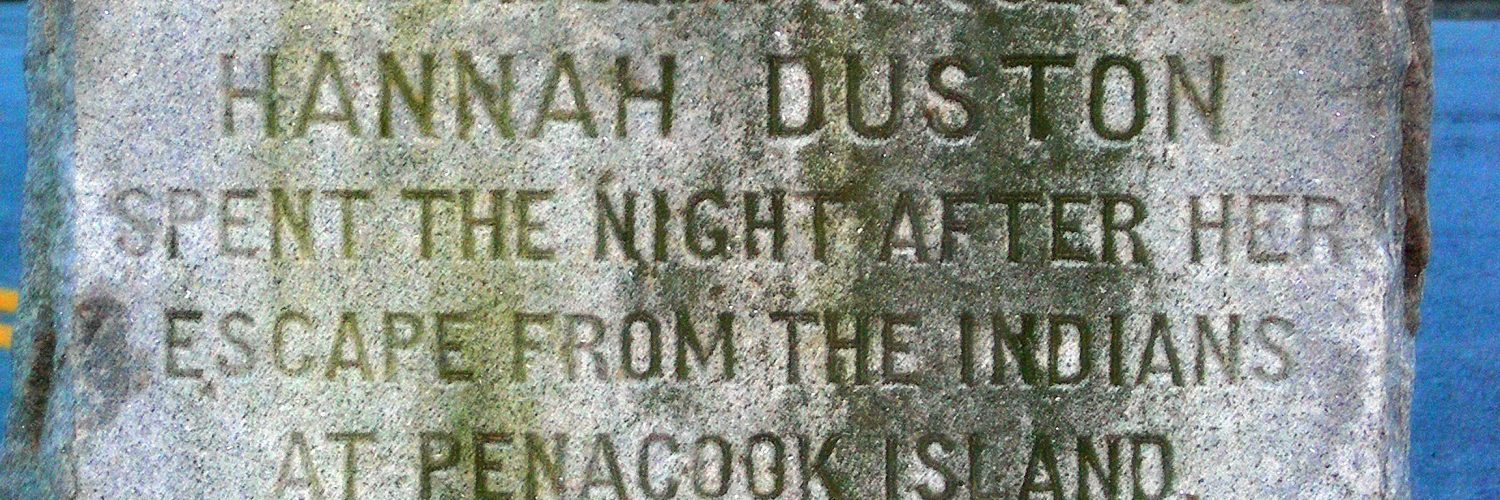

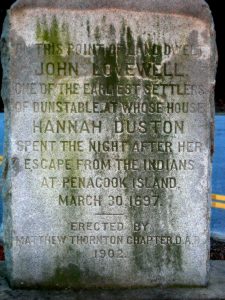

Here is where our pity turns to terror. Leonardson is said to have killed one of the men. By most accounts, Neff lost her nerve, perhaps being responsible for wounding the squaw who escaped (though not unscathed: she burst upon the camp upstream with seven ugly gashes in her head). The remaining nine victims were Hannah’s: a warrior, a squaw, and six children. The seventh child, she intended to take home. But she did not. We are not told what became of him except that he survived. It was a bloody scene, whichever side recounts it. And it would become more gruesome still. For after scuttling all but one canoe (presumably the survivors had to swim to shore), Hannah bethought herself of the scalps. Her stated motive for taking them was for proof of her story. Why she should think she would need such proof is unexplained. She probably had no thought of bounty. Bounties had been eliminated a year before. Perhaps she burned so with revenge that she wanted to give tit for tat. Perhaps she had worked herself into such frenzy that she wanted a trophy. We know that she had no second thoughts. She never dropped them regretfully into the Merrimack as they paddled toward home. Instead she kept them wrapped in the reclaimed cloth from her loom, perhaps showed them to John Lovewell, who gave them shelter for the night in Old Dunstable (now Nashua) before they made their way home overland to Haverhill; then she bore the trophies home to Thomas. Thomas thought their circumstances entitled them to the bounty even though it had been discontinued.

Once Hannah had rested from the ordeal she and Thomas went to Boston to make an appeal to the governor, who granted her a bounty of 25 pounds, and another 25 pounds to be split by Neff and Leonardson. While in Boston, she was received by Cotton Mather and Samuel Sewall. The governor of Maryland presented her with a silver tankard to celebrate her courage. Like the third little pig, Thomas Dustin built their new home of sturdy brick, which was soon established as a garrison. This home was built to last. It is still standing to this day. Little more is known of Hannah Dustin. She gave birth to a thirteenth (and final) child a year and a half later, and she lived to the remarkable age of 90.

A curious letter from Hannah was found at the church in the 1920s. She apparently wished to be restored to communion with the church after some absence. In it she wrote, “I am Thankful for my Captivity, twas the Comfortablest time that I ever had; In my Affliction God made his Word Comfortable to me. . . . I have had a great Desire to come to the Ordinance of the Lords Supper a Great while but fearing I should give offence & fearing my own un worthiness has kept me back. . . .” We cannot know what she referred to as cause for unworthiness. To the eyes of a modern reader it seems an indication of regret for her actions. It could be that she thought of her child victims. But it could as easily have been Sabbath-breaking or pride that troubled her conscience. Her world was different from ours. She and her companions may have reasoned that any survivors permitted to flee would bring down the wrath of the large settlement upstream. Indeed, the woman who escaped was not meant to do so: the only captor they had intended to spare was the surviving boy, and he they intended to take home with them. Such is the psychology of war. Soldiers make difficult, even unthinkable, decisions based upon equally unthinkable circumstances.

Like Hannah’s war, Hannah’s life was anchored to her Puritanism, which unlike modern Christianity, celebrated righteous violence. Churches now promote pacifism. But the Puritans were steeped in the retribution of the Old Testament, which was swift and sure, especially when the faithful were in captivity and persecuted for their faith. Cotton Mather compared her actions to those of Gael [Jael], who nailed the head of her enemy, Sisera, to the ground with a tent stake. As he saw it, “being where she had not her own life secured by any law unto her, she thought she was not forbidden by any law to take away the life of the murderers by whom her child had been butchered.” In fact, Mather, and undoubtedly Hannah’s party, regarded the incident as preordained. Mather refers to Bampico’s taunt, “when he saw them dejected . . . ‘What need you trouble your self? If your God will have you delivered, you shall be so!’ And it seems our God would have it so to be.”

And the scalps? We cannot be sure. They seem to have been an afterthought. In traditional accounts, the reason for taking them is to prove a story that otherwise would seem incredible. It could be that the scalps served as a bloody reminder of a hard won freedom. Or that she was driven solely by vengeance and a desire to inflict the final indignity: scalping at the hands of their own captives. Bampico may not only have given them a blueprint for the slayings but additional motive. Perhaps the lesson betrayed more enthusiasm than she could stomach. Perhaps, too, she imagined the scalps of her husband and remaining children (whose fates were still a mystery to her) upon the belt of some other warrior. If nine lives had been taken, this would even up the score—with one for lagniappe. Bloodthirsty? Yes. Understandable? Yes, once again.

And the scalps? We cannot be sure. They seem to have been an afterthought. In traditional accounts, the reason for taking them is to prove a story that otherwise would seem incredible. It could be that the scalps served as a bloody reminder of a hard won freedom. Or that she was driven solely by vengeance and a desire to inflict the final indignity: scalping at the hands of their own captives. Bampico may not only have given them a blueprint for the slayings but additional motive. Perhaps the lesson betrayed more enthusiasm than she could stomach. Perhaps, too, she imagined the scalps of her husband and remaining children (whose fates were still a mystery to her) upon the belt of some other warrior. If nine lives had been taken, this would even up the score—with one for lagniappe. Bloodthirsty? Yes. Understandable? Yes, once again.

With the passage of time, the perceptions of Hannah have gradually changed. Mather (1702) and Sewall (1697) believed she was an instrument of divine justice and providence.

But when Hawthorne told the story in 1836, he gave a very different picture. Never one to agree with Cotton Mather, that “hard-hearted, pedantic bigot,” about anything, he presented a harpy of a Hannah in the purplest passage Hawthorne ever wrote:

The work being finished, Mrs. Duston laid hold of the long black hair of the warriours, and the women, and the children, and took all their ten scalps, and left the island, which bears her name to this very day. According to our notion, it should be held accursed, for her sake. Would that the bloody old hag had been drowned in crossing Contocook river, or that she had sunk over head and ears in a swamp, and been there buried, till summoned forth to confront her victims at the Day of Judgement; or that she had gone astray and been starved to death in the forest, and nothing ever seen of her again, save her skeleton, with the ten scalps twisted round it for a girdle!

John Greenleaf Whittier, in his Legends of New England (1831), concentrates more on the human situation, which forced her to step outside the usual realm of womanhood:

Woman’s attributes are generally considered of a milder and purer character than those of man. The virtues of meek affection, of fervent piety, of winning sympathy and of that ‘charity which forgiveth often,’ are more peculiarly her own. Her sphere of action is generally limited to the endearments of the home- the quiet communion with her friends, and the angelic exercise of the kindly charities of existence. Yet there have been astonishing manifestations of female fortitude and power in the ruder and sterner trials of humanity; Manifestations of a courage rising almost to sublimity; the revelation of all those dark and terrible passions, which madden and distract the heart of manhood. The perils that surrounded the earliest settlers of New England were of the most terrible character. None but such a people as were our forefathers could have successfully sustained them. In the dangers and the hardihood of that perilous period, woman herself shared largely. It was not unfrequently her task to garrison the dwelling of her absent husband, and hold at bay the fierce savages in their hunt for blood. Many have left behind them a record of their sufferings and trials in the great wilderness, when in the bondage of the heathen, which are full of wonderful and romantic incidents, related however without ostentation, plainly and simply, as if the authors felt assured that they had only performed the task which Providence had set before them, and for which they could ask no tribute or admiration.

Whittier responds with admiration and a certain degree of fear when discussing the “astonishing manifestations of female fortitude and power” and a “courage rising almost to sublimity; the revelation of all those dark and terrible passions, which madden and distract the heart of manhood.” Much as he praises her courage, Whittier plainly prefers the more predictable support of a woman whose “sphere of action is generally limited to the endearments of the home.” Someone you could take home to Mother. He also seems, like most of us, to be grateful to have been born in a different and safer era.

Finally, Thoreau (1849) presents us with an uncanny picture of the fugitives’ journey home along the usually pastoral backdrop of the Merrimack River, now fraught with unknown terrors,

while their canoe glides under these pine roots whose stumps are still standing on the bank. They are thinking of the dead whom they have left behind on that solitary isle far up the stream, and of the relentless living warriors who are in pursuit. Every withered leaf which the winter has left seems to know their story, and in its rustling to repeat it and betray them. An Indian lurks behind every rock and pine, and their nerves cannot bear the tapping of a woodpecker. Or they forget their own dangers and their deeds in conjecturing the fate of their kindred, and whether, if they escape the Indians, they shall find the former still alive. They do not stop to cook their meals upon the bank, nor land, except to carry their canoe about the falls. The stolen birch forgets its master and does them good service, and the swollen current bears them swiftly along with little need of the paddle, except to steer and keep them warm by exercise. For ice is floating in the river; the spring is opening; the muskrat and the beaver are driven out of their holes by the flood; deer gaze at them from the bank; a few faint-singing forest birds, perchance, fly across the river to the northernmost shore; the fish-hawk sails and screams overhead, and geese fly over with a startling clangor; but they do not observe these things, or they speedily forget them. They do not smile or chat all day. Sometimes they pass an Indian grave surrounded by its paling on the bank, or the frame of a wigwam, with a few coals left behind, or the withered stalks still rustling in the Indian’s solitary cornfield on the interval. The birch stripped of its bark, or the charred stump where a tree has been burned down to be made into a canoe, these are the only traces of man,—a fabulous wild man to us. On either side, the primeval forest stretches away uninterrupted to Canada, or to the “South Sea”; to the white man a drear and howling wilderness, but to the Indian a home, adapted to his nature, and cheerful as the smile of the Great Spirit.

From then on she was absorbed into the popular culture of the region, through childhood history lessons and landmarks. Hannah Dustin would become a symbol of colonial spirit. Her name would be attached to streets, the island she escaped from, finally restaurants and motels. Like Lizzie Borden she was immortalized in light verse. That poem, like Lizzie’s quatrain, sacrifices accuracy for comic effect (doubling the number of victims and omitting the unhumorous fate of Martha). Though not so well known, the poem is vastly superior:

“The Lady of the Tomahawk “

by Robert P. Tristram Coffin

Hannah was a lady,

She had a feather-bed,

And she’d worked Jonah and the whale

Upon the linen spread,

She did her honest household part

To give our land a godly start.

Red Injuns broke the china

Her use had never flawed,

They ripped her goose-tick up with knives

And shook the down abroad.

They took her up the Merrimac

With only one shirt to her back.

Hannah Dustin pondered

On her cupboard’s wrongs,

Hannah Dustin duly mastered

The red-hot Injun songs.

She lay beside her brand new mates

Remembering the Derby plates.

She got the chief to show her

How he aimed his blow

And cut the white man’s crop of hair

And left the brains to show.

The Lord had made her quick to learn

The way to carve or chop or churn.

The moon was on the hilltop,

Sleep was on the waves,

Hannah took the tomahawk

And scalped all twenty braves.

She left her master last of all,

And at the ears she shaved his poll.

Homeward down the river

She paddled her canoe.

She went to her old cellar-place

To see what she could do.

She found some bits of plates that matched,

What plates she could she went and patched.

She built her chimney higher

Than it had been before,

She hung her twenty sable scalps

Above her modest door.

She sat a-plucking new gray geese

For new mattresses in peace.

Hannah was never, like Lizzie, made into a bobblehead, but she was made into a figural Jim Beam bottle in 1973—not quite as good as having her picture on a bubble gum card, but close enough. Hannah created a brief stir last year, when she was made into the poster girl for the “Haverhill Rocks” concert. Her bronze image was shown with hatchet traded in for a shiny red electric guitar. The poster and subsequent proposal for a formal Hannah Duston Day each March, to breathe new life into the struggling mill town, were met by outrage on the part of the Abenaki Nation and many citizens across the region. The media attention drawn to the cause, of course, did nothing but pique the interest of Hollywood.

Now that media interest has faded, most New Englanders find her name vaguely familiar, but few outside Haverhill can give her story. If it weren’t for the scalps, she would make an ideal symbol for woman’s empowerment, but the scalps get in the way these days. People haven’t the stomach for it. Even without the in-your-face posters, many Haverhill citizens grow evasive at the mention of her name. When Sybil Smith, Dustin descendant and writer, visited the Haverhill Historical Museum she received a chilly reception:

I explained right away that I was related to Hannah Duston. She seemed impressed and uneasy. It was her first day, she said. Her first tour.

I wanted to see the relics of Hannah right away, but she had other plans. We would, for our money, be given the official tour.

So there we stood in the entrance hall. The first exhibit concerned the Algonquian Indians. There was a model canoe, as I recall. There was an exhibit of stone tools, bone implements, baskets, and a tableau of the Indian method for drying fish.

Next we were led into a sort of classroom. The guide popped a video into a TV that stood in one corner. We sat there bemusedly, prepared for curious facts and pithy truths. The sound of chants and drumbeats filled the room. It seemed we weren’t done with the Indians. The film was grainy and serious. I couldn’t pay attention, bombarded as I was by the ironies of time.

Our guide stood nervously to one side. I bore down on her with my handful of genealogies. Indian singing sounded in the distance, as my fingers descended the family tree.

At last she showed me the documents encased in glass on the walls. Here was Cotton Mather’s account of Hannah’s captivity and escape. And finally, in a large, cold room jammed with curios, we saw what are believed to be Hannah’s hatchet, the scalping knife, her teapot, her buttons.

Ironically, her impressions are nearly identical to mine at the Fall River Historical Society when I asked about the Borden collection. Fall River prefers to remember the bustling town of the gilded age. Haverhill now prefers to present itself as an archive for Native American relics. And so history is written and rewritten.

Ironically, her impressions are nearly identical to mine at the Fall River Historical Society when I asked about the Borden collection. Fall River prefers to remember the bustling town of the gilded age. Haverhill now prefers to present itself as an archive for Native American relics. And so history is written and rewritten.

The bronze statue remains safe and well tended in the center of Haverhill, her face stern as she raises her hatchet at nothing more menacing than a double-parked car. A few weeks ago I paid a visit to her poorer cousin on Dustin Island, outside Penacook. Her sculptor had less skill, yet she has an eerier quality than the statue in Haverhill. Perhaps it is the setting, which on a warm January afternoon must have been very like the scene she arrived at that March day. It looks barren, half forgotten, like the abandoned railway and half demolished trestle that lie on either side of her. She is cruelly disfigured by spray paint—not applied by activists: there are no signs of protests, only paint sprayed by some small town wannabe gang members who chose to mark their territory on a patch of unpatrolled ground. The painted numbers and initials swirl about the pediment, and one intrepid soul was industrious enough to soil her gown. But Hannah gazes out with an air of satisfaction—her face serene, almost on the verge of smiling. This Hannah’s hatchet is at her side. The other hand gracefully holds what appears to be a nosegay. It is instead the fortune of war.

Works Cited:

Coffin, Robert P. Tristram. “The Lady of the Tomahawk” Collected Poems of Robert P. Tristram Coffin. NY: Macmillan, 1939: 58.

Hannah Dustin / Duston of Haverhill, Mass. “The Story of Hannah Dustin/Duston.” 2006. 26 January 2007 <http://www.hannahdustin.com/hannah_files.html>.

Hawthorne in Salem—Homepage. “Explore Activities Related to Indians in ‘Main Street.’” 31 May 2003. North Shore Community College, Danvers, MA. 26 January 2007 <http://www.hawthorneinsalem.org/page/12145/>.

Hawthorne in Salem—Homepage. “H. D. Thoreau’s Retelling of the Hannah Dustin Story.” 31 May 2003. North Shore Community College, Danvers, MA. 26 January 2007 <http://www.hawthorneinsalem.org/page/11869/>.

Jimenez, Ralph. “Some N.H. Statuary Eroding Molecule by Molecule.” Boston Globe 31 March 1991.

Long, Tom. “Heroism is in the Eye of the Beholder.” Boston Globe 3 September 2006.

Perrielo, Brad. “Proposed Hannah Duston Day appalls American Indian leaders.” Eagle-Tribune (North Andover, MA) 27 August 2006. 26 January 2007 <http://www.eagletribune.com/local/local_story_239063934/>.

Smith, Sybil. “Judging Hannah.” Yankee Magazine Jan. 1995: 50.

Stillman, Jim. “The Story of Hannah Dustin – Joan of Arc or Lizzie Bordon? Colonial Woman Kills Her Kidnapper Indians, Becomes a Heroine.” Associated Content 20 November 2006. 26 January 2007 <http://www.eagletribune.com/local/local_story_239063934/>.