by Eugene Hosey

First published in Winter, 2013, Volume 8, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Neorealism was a style of filmmaking developed literally as World War II was ending in Europe. The goal behind this kind of cinema was to show life as it really was in actual places using residents instead of professional actors. These films tended to deal with the struggles of the poor. Two of the earliest films to come from this movement, Open City and Bicycle Thief, are considered masterpieces, outstanding examples of the style and spirit of the genre. This approach to filmmaking caught on with many of the great European filmmakers, and neorealism was a force until the early 1950s. Shoeshine, Germany Year Zero, and Umberto D are just three other examples that received wide acclaim.

Neorealism was a style of filmmaking developed literally as World War II was ending in Europe. The goal behind this kind of cinema was to show life as it really was in actual places using residents instead of professional actors. These films tended to deal with the struggles of the poor. Two of the earliest films to come from this movement, Open City and Bicycle Thief, are considered masterpieces, outstanding examples of the style and spirit of the genre. This approach to filmmaking caught on with many of the great European filmmakers, and neorealism was a force until the early 1950s. Shoeshine, Germany Year Zero, and Umberto D are just three other examples that received wide acclaim.

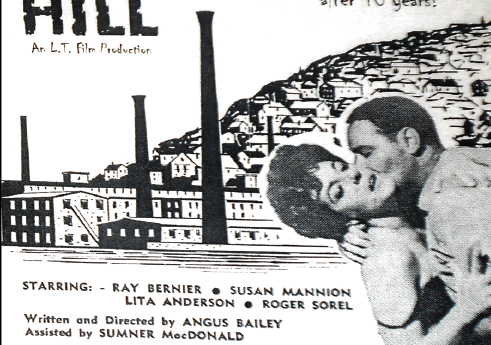

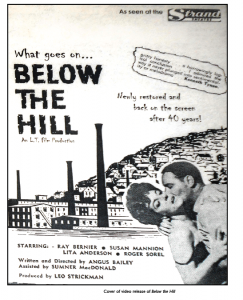

The 1963 film, Below the Hill, is Fall River’s contribution to movie-making that is informed by a real place and time where local people are besieged by social/economic problems. The project was created by a Fall River Community Theatre group, written and directed by Angus Bailey. The film’s style is simple; it uses an almost documentary approach and deliberately avoids cinematic artifice and fancy camera work. The only aesthetic trick utilized is the smearing of Vaseline or something like it on the edges of the frame to produce a dreamy effect when the central character is remembering his past.

As the film opens we see fired millworkers streaming outside. The protagonist, Fred, is 30 years old and baffled as to what his next move should be. He has worked in the mill since he was 16, he says, as he converses with an old man who is ready for retirement. Fred has assumed he would likewise dedicate himself to the mills, and the loss of his job creates in him a frightening feeling of insecurity.

In the Italian masterpiece of the genre, Bicycle Thief, the protagonist is the victim of theft as he struggles energetically to survive a terrible unemployment problem. He is fortunate enough to find a job pasting up movie posters around Rome; he must have a bicycle to cover his route. When his bicycle is stolen, he conducts a desperate search, and this becomes the story. Without his transportation, the job will be lost. The noble struggle to take care of his family through honest work is the crucial theme in this Italian classic; the morality of this awful matter is effectively challenged when these maddening circumstances temporarily defeat the integrity of the protagonist, and he loses his head and attempts theft himself.

Conversely, one can’t help but notice in Below the Hill a deficiency of the noble human spirit. The main character suffers from moroseness, and those who influence him are discouraging and incompetent. The type of resourcefulness we do see is either pathetic or seriously harmful. As the story moves along, it is apparent that no one will find a way to circumvent the coming doom.

The filmmaker is making a statement about the damaged condition of the Fall River lower working classes of the early 1960s. “Below the hill” is a local term for the blue-collar mill district along the river, a once-industrious place now crumbling. What is interesting is how mere familiarity with this area and its low wages are just sustaining enough to keep this segment of society precariously intact and satisfied. With the failing of the mills, poverty seems to lurk in general. For Fred, in particular, the death of his mill-working future is not merely a financial misfortune. The loss of his job becomes the avenue down which darker issues are exposed about his marriage. We definitely sense that deep-seated problems have been festering all along but have been kept at bay by the assumption of a stable job. Once Fred loses his job security, unhappiness and even hatred get the upper hand and everything turns ugly.

Actually Fred is able to find another job, although it doesn’t pay enough to suit his wife Claire, who manages to find a job for herself. Hers seems to be a better one. Finally the couple antagonize and alienate each other, and the relationship is ruined. The devastation raises gender issues. The wife wants security and the husband wants her to believe in him. But Claire is disgusted by what she can define only as Fred’s weakness as he flounders. This crushes Fred’s ego. Finally she loses all respect for him and tells him she actually doesn’t need him anymore. It would appear that the wife never had much love for her husband and finds it impossible to be supportive. Apparently, Fred derived all his self-esteem from the mill and his marriage and is unremittingly confused without them. As his wife fades from his life, he often drifts into daydreams about the early days between them when he at least thought they were happy.

Below the Hill is less about the struggle to overcome poverty—and more acutely about how the loss of occupation and dignity can open infectious wounds and lead to cruel irresponsible notions. One can find a moral message in the film about the absolute necessity of love in the human heart. Otherwise it is evil that rules, both leading and following those so unfortunate.

The filmmaker is fairly obsessed in showing the sinister side of human nature. The couple who lives in the other half of the tenement consists of a man who is into dirty dealings and a wife who is something of a nymphomaniac. The story piles on the crude and the lurid. Fred is ruthlessly humiliated. For example, there is an odd scene of him playing ball with a little girl in a park; without audible dialog a policeman walks up to Fred and gestures him to move along, as if the policeman suspects he may be a child molester. Poor Fred—he isn’t. There is also a negative attitude about homosexuality, used as insult, worked in the dialog at least twice. At a bar, the waiter makes a “come here” gesture to a man. Although this is really about some illegal money-making scheme, the drunk wife of the man pipes up with a “What is he—queer or something?” Another time when Fred’s wife plans to go out with some of the girls, Fred takes offense and says, “You can’t care that much about havin suppa with a bunch of girls, unless there’s somethin wrong with ya.” Such old-fashioned ideas may bother some people today, but it should be remembered that this film purposely uses the typical speech of its time.

Below the Hill is about people who are victims of sorry circumstances. Also they are not brilliant with ideas about changes that could possibly be within their power to make. The filmmaker shows a district of Fall River that is by definition so negative that it can actually become an experience of enslavement. Fred becomes a prisoner—all his hopes and options finally dead.

There are many neorealist masterpieces that should be seen by all film lovers. Below the Hill is not a masterpiece. It is a look at a place in the past. Concerning the realism and truth of the film, those people who were alive in the Fall River of the early 1960s are the ones to ask. I think what keeps this from being a much better film is its unrelenting negativism. A sad film that is well made can be a wonderfully uplifting, enlightening experience, but Below the Hill is not. One of the hallmarks of classic neorealism was the hope and love that could soar above poverty and misfortune regardless of the fates of the characters. Nobody is clear-headed or tries hard enough in this movie. But it is an historical document, and it belongs to Fall River.