by Eugene Hosey

First published in April/May, 2008, Volume 5, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

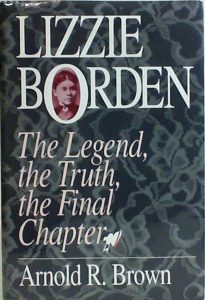

The publication of a nonfiction book that identified a mystery person as the murderer was the logical progression in the literature of the Lizzie Borden story. Accomplished writers such as Edmund Pearson and Victoria Lincoln have explored Lizzie as axe murderess. Radin named Bridget as the culprit; Spiering accused Emma. And Morse has been something of an accomplice in several accounts. To the credit of Brown (or to any author who might have done it), fans and scholars need the study of a shadowy, mystery killer in the ongoing debate. This type of solution is always going to be potentially interesting, if not enlightening, since the unknown mystery killer, in theory, cannot be disproved. Once we accept the overwhelming probability that a solution—no matter how scholarly and well researched it may be—cannot actually be proven, then the value of this hypothesis must ultimately exist in the story itself. Does it resonate at every level? Does it meet the requirements of known facts and explain a multitude of mysteries? The author Brown does claim something close to this in the chapter that explains murder morning:

The publication of a nonfiction book that identified a mystery person as the murderer was the logical progression in the literature of the Lizzie Borden story. Accomplished writers such as Edmund Pearson and Victoria Lincoln have explored Lizzie as axe murderess. Radin named Bridget as the culprit; Spiering accused Emma. And Morse has been something of an accomplice in several accounts. To the credit of Brown (or to any author who might have done it), fans and scholars need the study of a shadowy, mystery killer in the ongoing debate. This type of solution is always going to be potentially interesting, if not enlightening, since the unknown mystery killer, in theory, cannot be disproved. Once we accept the overwhelming probability that a solution—no matter how scholarly and well researched it may be—cannot actually be proven, then the value of this hypothesis must ultimately exist in the story itself. Does it resonate at every level? Does it meet the requirements of known facts and explain a multitude of mysteries? The author Brown does claim something close to this in the chapter that explains murder morning:

What follows is supposition. While there may be a minimum of objective evidence to prove it is true, there is no evidence that demonstrates it is not true. And it is more consistent with all the testimony and evidence presented at every public hearing and at the trial than any other explanation I know.

According to Arnold Brown’s Lizzie Borden: The Legend, the Truth, the Final Chapter, the killer of the Bordens was the illegitimate son of Andrew Borden, conceived during Andrew’s marriage to Sarah. The mother and her husband, another Borden, raised this child, William. William knew about his parentage and may have received some support from his biological father. Bill Borden was not exactly right in the head. He was skilled as a butcher and had an axe fetish, keeping the weapon on his person and talking to it as if it were a companion or a Freudian extension of his baser self. He bore a grudge against his father, and this animosity finally exploded on August 4, 1892.

Brown came by this information through a friend and fellow native of Fall River. The friend’s father-in-law, Henry Hawthorne, had spent part of his childhood on Bill Borden’s farm, and later came to believe that this menacing figure who had frightened him as a boy was actually the killer of the Bordens. Mr. Hawthorne married the daughter of Ellen Eagan, and by some remarkable coincidence, his mother-in-law had an eerie Borden memory of her own. She claimed to have seen a malevolent, foul-smelling man in the Borden yard on the morning of the murders when she became sick while walking down Second Street. The clue that convinced Henry Hawthorne that the man Ellen Eagan had seen was Bill Borden was the unusually offensive odor. Mr. Hawthorne had experienced this himself in connection with Bill Borden, who habitually made a hard cider that would render a terrible, peculiar odor if it went bad or if a cask became contaminated. After cleaning Bill Borden’s casks for the season, Borden made Hawthorne clean himself with “something that looked like axle grease and a cake of lye soap and be sure to rub this secret grease on all the spots of his body where the cider residue and the cleaner had come in contact.” Henry followed Borden’s instructions and after his bath, “he noticed the foulest odor he had ever smelled.” In an apparent practical joke, Borden had spiked his salve with horse urine from a dead equine that died from Blister Beetle Poisoning. Additionally, Hawthorne remembered some incriminating things Bill said to his axe. And this is essentially the basis for the whole theory. Brown claimed to have a notebook of Hawthorne’s writings, but he does not quote from this source or even show us a facsimile of it.

Although there is a public record for the existence of a William Borden, Brown has no source whatsoever for his theory that this man is actually the son of Andrew Borden. This connection exists only in Hawthorne’s childhood memories of odd, cryptic statements made by Bill Borden. There is no evidence, even of a secondary nature, that links Andrew to William Borden.

Is the story believable in any sense? Family secrets, skeletons in the Borden closet—these should come as no great surprise to those familiar with the case. The plausibility of Brown’s theory is aided by the fact that a Bill Borden as killer makes it an “inside” job—a stranger to us but not to the Borden family. And finally, yet importantly, it certainly makes sense that the killer is a butcher by trade.

Brown believes that Bill Borden entered the house the night of August 3 and slept either in the room with Morse, in Emma’s room, or in the barn. There was to be a meeting between Andrew Borden and his disgruntled, illegitimate son. But, obviously, something went wrong, beginning with an unplanned, fatal meeting between the son and Abby Borden in the guest room. According to the theory, Lizzie did not know that murder had occurred until she found her father’s body. She knew her half brother was waiting upstairs for Andrew to get home, but she was deliberately avoiding him while under the assumption that Abby had left the house. Could Lizzie have failed to overhear the first murder? Perhaps, if she were in the cellar or outside the house at the crucial time. During the second murder, Lizzie was eating pears in the backyard. Lizzie’s silence about the murderer’s identity was because of family pride and legalistic concerns about the inheritance of Andrew’s estate. As for some of those puzzling mysteries, Brown has no explanation for Lizzie’s dress burning; he calls Lizzie’s attempt to buy prussic acid an act of self-defense. Brown adds some interesting touches, such as his idea that the laugh Bridget heard upstairs while she was at the front door was not the laugh of Lizzie Borden, but that of her illegitimate brother.

Readers must judge for themselves the credibility of Arnold Brown’s theory. Unfortunately, there are no facts that can be used to assist in making this decision. One has only the knowledge, intelligence, and intuition as possessed by the discerning individual.

Brown’s obsession with conspiracy certainly does not clarify or strengthen his theory, although his belief that the Borden case was one huge charade on the part of the justice system from start to finish is where he spends the bulk of his book. Brown claims that a secret organization called the Mellen House gang (named after the hotel, their meeting place) coordinated the phony trial and its outcome with the cooperation of Lizzie herself—the court officials and lawyers all being members of this organization. Brown finds revelations of conspiracy in simple choices of words directed at, or answered from, the witness stand. He finds them in questions not asked, in things unsaid. Knowlton’s question to Lizzie about the number of Andrew’s children, “Only you two?” becomes a secret communication about the illegitimate son.

Brown comes across as a true conspiracy buff. He determines that the defense attempted to bribe Eli Bence for the flimsiest of reasons—a reference made by Bence to an unspecified person or persons. The author goes on to find guilty knowledge on the part of Borden trial author, Edwin Porter, in Porter’s use of the word “guiltless”—as opposed to “innocent”—in describing Lizzie in the last sentence of his book, The Fall River Tragedy: A History of the Borden Murders. Brown’s suspicious reasonings become hopelessly complicated and tiresome. This characteristic is not a strong indicator of truth.

Given the popularity of conspiracy theories in general, perhaps it is also inevitable that someone would try to convince us that the trial of Lizzie Borden was a total setup. Had Brown been able to stand on the plausibility of his theory about the murderer’s identity by giving us more pertinent information, the theory might have had more power. But the whole William Borden story is deficient in supportive facts. He might have uncovered a local myth about the murders, but this is certainly not the “final chapter.” While this book may not stand the test of thoughtful reasoning and deep consideration, it does at least open up and broaden the debate. Arnold Brown did this much if nothing else.