by Stefani Koorey

First published in November/December, 2007, Volume 4, Issue 4, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

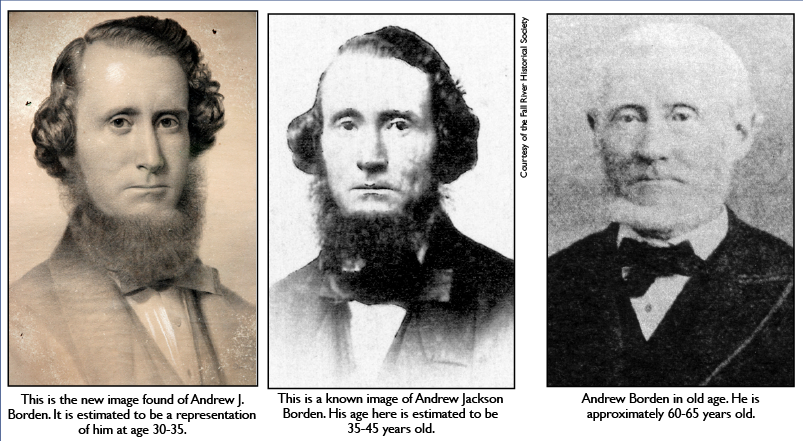

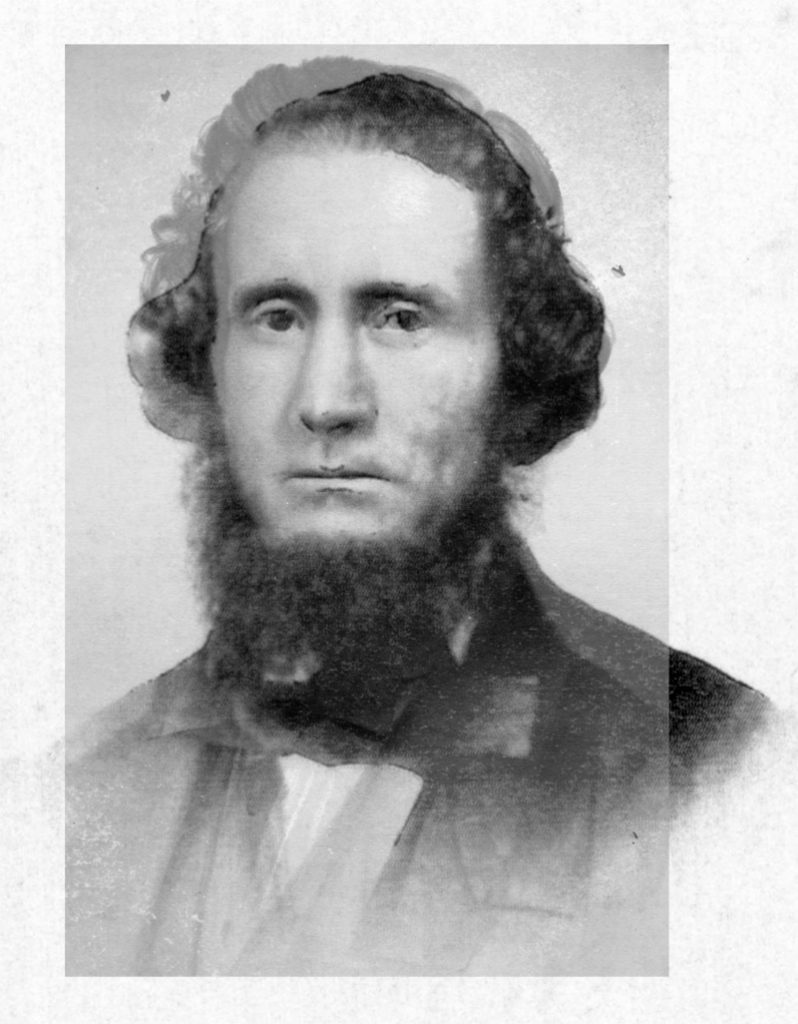

A new image of Andrew Jackson Borden, father of accused and acquitted hatchet murderess Lizzie Borden, has been found collecting dust in a Massachusetts museum. The picture shows Andrew as a young man, about 30-35 years of age, before the years deepened his frown into the stoic, Calvinistic, stern-faced icon of Yankee seriousness. Here we see the hopeful Andrew, a man with a lifetime ahead of him. Little does he know that his life will be cut short by eleven bloody whacks.

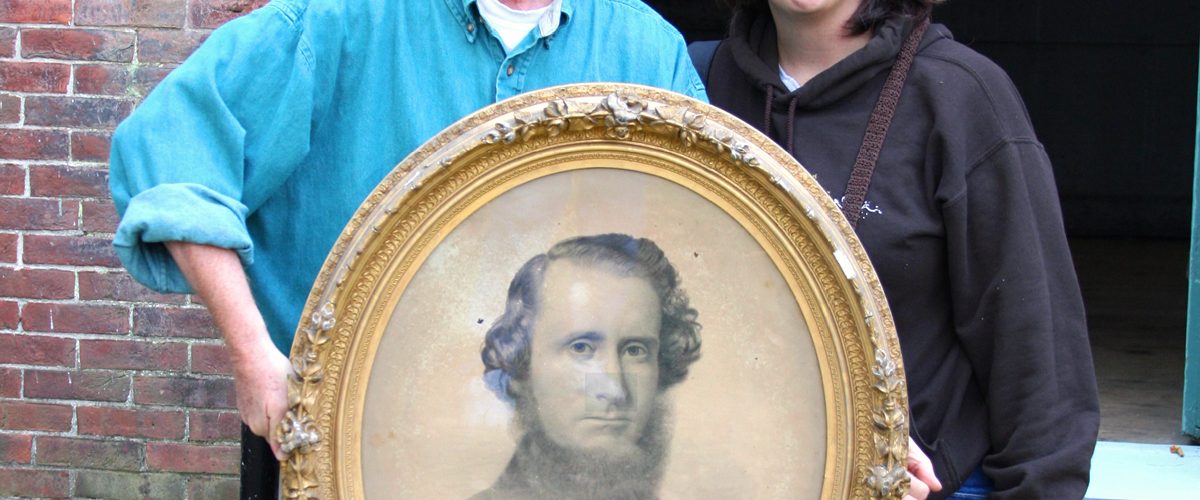

The August Saturday morning was damp and cool as Shelley Dziedzic and I arrived at the museum. We had arranged for the tour with the curator in advance and were expected, but we arrived a bit late because Shelley, the day’s driver, had worked late the night before as house manager at the Lizzie Borden Bed and Breakfast. She had been up all night with guests who were eager to pick her brain about all things Borden. She was operating on pure caffeine and adrenaline and I excused her immediately when I heard her tale of the last evening’s adventures. I was hoping that the curator would arrive late as well.

He didn’t. He smiled and waved at us as we pulled onto the grass driveway just off the intersection. We spent the first few minutes of our meeting apologizing for our dilatoriness, for which he graciously excused us.

Before we entered the premises, we strolled the grounds with our host and snapped our “outside” photos of the building and its brick construction. A large dog barked in the neighboring yard as we circumnavigated the structure, marveling at its age and imagining the riches it contained.

The curator, a charming man, was eager to open up the collection for us, his only visitors. We had come to view this compact museum’s entire contents, but were most interested in seeing a particular display that we had heard and read about. After our 90-minute visit, we each came away with separate unexpected discoveries that related to our own areas of study. Shelley was thrilled to find an extensive collection of Victorian funereal artifacts, including a child’s casket, an undertaker’s board for autopsies, and a viewing casket, and I was ecstatic that I had chanced upon what I thought was something no one had ever recognized before—an unknown image of Andrew Borden.

We had come to Luther’s Museum in Swansea, Massachusetts, to see Lizzie Borden’s chairs. Andrew Borden had owned two tracts of land in Swansea, unimaginatively known as the upper and lower farms. It was at the upper farm, on Gardner’s Neck Road, that the Borden family at one time shared a farmhouse and barn with Andrew’s business partner, William Almy. Built in the 1790s by Joseph Gardner, the farm was a place where the Bordens spent their summers and escaped from the hubbub of Fall River’s nineteenth century milieu.

Five rickety chairs and a table, which had been used on the porch, had been donated to the museum in years past, and now were tagged and shown to visitors to Luther’s as coming from the Borden farm. The provenance of the Borden’s ownership was sound, as it is for most of the items in the collection at Luther’s. A preponderance of the artifacts have been labeled as to the identity of the donor and the age of the item, with a brief description of what the item was or used for. In some cases, it was difficult to determine an object’s name or use as they had long since become obsolete. Until I read the tags, to me these bygone objects were known as doodads, thingamajigs, thingamabobs, whatsits, whatchamacallits, thingys, and doohickeys.

There are some pieces in the collection, however, that have no tags or marks identifying anything about them. For instance, at one point I inquired as to the identity of the man in a framed photograph. Carl honestly replied, “Take it off the wall and look on the back. It might be marked, and then we will both know.”

Luther’s museum is maintained by the Swansea Historical Society and is a one-man operation. Carl Becker, the town’s Historian and museum curator, conducts tours for students, runs the museum, and cleans and arranges the artifacts for display. Luther’s Museum is in dire need of a heating system so that it can be open during the long winter months. Currently, the museum is only open during the spring and summer.

The museum has two floors and an unused small cellar. The first floor looks much as it did in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when it was a general store. Writes Kat Koorey in the August issue of The Hatchet of her visit there in early 2007, Luther’s contains original counters, bins, drawers, shelves, scales and Mr. Luther’s desk where he kept his accounts. There are still intact original items sold at the store, and also a fine collection of period pieces that have been donated to the society. There are posters, handbills, advertisements, signage, photographs and pictures on the walls, and in one area where the scales had been popular, customers have written their names and weight on the walls in faded lettering.

On the second floor are displayed tools of the old trades of cobbler and hat maker, and an array of coffins of several sizes that had been offered for sale. One unusual coffin had a storage area built in for ice to keep the body cool longer in warm weather. It has a viewing window with a cover one can open or close. There is a long, large cradle displayed in the museum, which was designed to rock the elderly infirm adults, and is similar to one at General Artemus Ward’s place in Shrewsbury, and one other in the infirmary of the Hancock Shaker village, according to our guide, Carl. There were so many miscellaneous items of furniture, pictures, accounts and artifacts that we could not take it all in and cannot wait to return for another visit.

An area that Kat Koorey does not describe is a small room on the second floor on the south side of the museum. It is here where paper items such as nineteenth century magazines and publications, newspapers, and books belonging to the Gardner family can be found. The room is about the size of a bathroom, and was possibly used as a closet or storage area in the past.

While Shelley was quizzing Carl about the funerary items in the larger room, I was drawn to the books and busied myself in opening a random cover, hoping to know by sight the name of an owner. The very first book I picked up had “Orrin Gardner” written on the flyleaf in a flowing script. I recognized the name immediately.

Orrin was a cousin to Andrew’s daughters and a close friend of Emma Borden. In 1896, the Fall River newspapers reported that Lizzie and Orrin were engaged to be married. This was denied by both sister Emma and Orrin in statements to the paper on the 12th of December of that year.

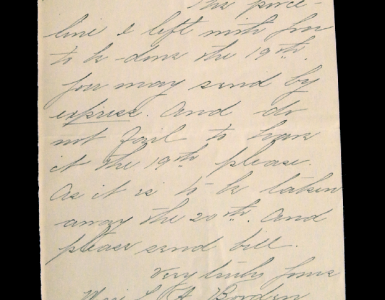

We know that Emma particularly cared for him. In her will, Emma left Orrin the sum of $10,000 “and all of my household furniture and furnishings, including all books, pictures, ornaments and personal effects not otherwise disposed of in this will, if he shall survive me.”

Did Emma leave Orrin the furnishings of the Borden farm in Swansea as well? One can only guess.

As I perused the bookcases stored in this tiny chamber, I happened to glance at the two framed charcoal portraits that were on the floor under the window, beneath a board shelf that contained more old books of all sizes. There, covered in dust and balanced precariously on its oval chipped frame, was a face that I recognized. I did a double and then a triple take. Could it be? Nah. It couldn’t be, could it? Was it possible that here, before me, was Andrew Borden? If so, the implications were significant. It meant that no one, ever, had recognized this image as Andrew before—not the many visitors to the museum, including Borden scholars who had also paid a call, not the curator, or members of the board of the Swansea Historical Society. In my mind, I weighed the odds. They were stacked against my first instinct.

I picked up the large picture to examine it more closely, turning it over to see if there were any markings or identification notes on the reverse of the frame. There was nothing written on the back nor was there a tag on the item.

The more I looked at the whiskered face of the young man, the more I was drawn to the possibility. I interrupted Carl and Shelley and asked him if he knew who the man was. He said that he didn’t. I said, “Looks like Andrew.” Shelley agreed and returned to her caskets and Carl’s description of their use.

I took a few photos of the picture to look at later, and Shelley and I concluded our wonderful visit.

Since that first visit to Luther’s Museum, I have shown my photographs of the man in the portrait to three different Borden scholars and to the curator and assistant curator of the Fall River Historical Society. The scholars are firm in their belief it is Andrew Borden. Michael Martins, curator of the Fall River Historical Society, is also of the opinion that this image is most probably Andrew. It makes sense, he says, that it would be located at Luther’s Museum, when they also possess other Borden-owned items.

It was while speaking with Michael Martins that I also learned about the process involved in creating these portraits. Popular in the 19th and 20th centuries, charcoal portraits were relatively inexpensive to produce. One technique was to overpaint enlarged photographs with charcoal and white pencil to enhance the original photo and retouch the image to produce a better looking subject. Here, the human artist served the same function as Photoshop does today!

Another charcoal portraiture technique was to enlarge the photograph and make the drawing from the image, but not on the image. It saved the subject from having to sit for hours for the likeness to be completed as the artist used the photograph, and not the actual human, as their guide. Apparently, photography studios routinely employed artists to make the portraits, sometimes charging as little as $2 for the process.

According to James M. Reilly in his Care and Identification of 19th-Century Photographic Prints (Eastman Kodak, 1986),

The largest class of prints made for development during that period [1840-1885] were enlargements called ‘crayon portraits,’ in which a weak photographic image was used as the basis for extensive handwork with charcoal and pastels. They were made from the 1860s through the turn of the 20th century. Both printed-out and developed-out images were used as a basis for applied coloring, but the life-sized crayon portraits usually employed a neutral black, developed-out image on a ‘matte surface’ paper as the underlying photographic ‘sketch.’

Further study of this Andrew image will have to be made to ascertain whether it was produced by overpainting or as a fresh portrait from a photograph. Part of any preservation process will include this determination. To be sure, the picture and period frame are in need of restoration and conservation, which can be an expensive process, conceivably in upwards of $5,000. As you can see from the cover photograph, there are several holes around the face that require professional attention, and a good cleaning is in order. I noticed that the frame is also problematic, as there are chips in the wood and multiple places where the gilt is missing. Overall, however, the portrait is in remarkable shape considering its age!

When one compares the new image with the two other accepted Andrew photos, one can clearly see important similarities between these and the newly found portrait. Particularly distinguishable are the areas around the mouth, especially under the lips. Notice the indentation there, as it is a unique feature. Also pay close attention in the two younger images to Andrew’s hair and the part in the style, the size and shape of the forehead, and fashion of the beard. They are nearly identical.

Now notice the eyebrows. In the middle photo, Andrew has very distinctively shaped eyebrows. His right brow is more oval, almost moon-shaped and curves around the eye. The left eyebrow is different than the right. It is not curved but straight, across the eye area, then curves down at the end.

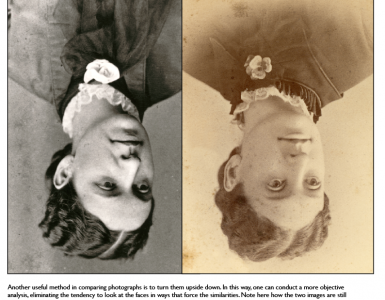

Of course, forensic facial recognition involves calculating distances between the ears, nose, mouth, and eyes to determine identity. With our modern ability to change the size of images and overlay them, using transparency or adjusting the opacity of layers, as in Photoshop, we can place one face on another to see how these ratios of facial features compare.

This last photograph is a composite. The newer image has been flipped horizontally so that both faces are looking to the left. I then superimposed the new image, which is at half opacity, on the known image. The distance between the eyes matches exactly! In addition, the relationship between the nose, mouth, and eyes shows that same remarkable likeness. More evidence to prove that the man in the portrait is Andrew Jackson Borden, an overwhelmingly exciting discovery!