by Stefani Koorey

First published in January/February, 2008, Volume 5, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Just when you least expect it, right before your eyes are objects of wonder and delight. A veritable treasure trove of undiscovered images, books, documents, and portraits.

Last August, while touring Luther’s Museum in Swansea, Massachusetts, I happened upon a previously unseen large oval gilt-framed portrait of Andrew Jackson Borden as a younger man. It was a momentous discovery and one that made the local news, eventually being picked up by larger press syndicates. I wrote about the find in this very journal, The Hatchet, in November 2007. Over the years I have trained my eyes to be ever vigilant for all things Borden, from recognizable book spines in used and antiquarian book shops, auction houses, and Fall River area locations, to Borden and Morse family likenesses in the faces that stare back at me from period cabinet photographs and scrapbooks.

I have come across a few good deals in my lifetime, and was even able to snap up a copy of The Knowlton Papers (valued now at about $300) for twenty bucks at Gotham Books in New York City. But I had never found anything “new” or of real significance. Those types of discoveries were for the lucky—or so I believed. Now I know that luck has only a small part to play in the uncovering of the previously unnoticed. What makes all the difference in the world is hard work, perseverance, and a dogged commitment to earnest scholarship. Oh, and a big helping of optimism thrown in for good measure.

In December of 2007, I returned to Luther’s Museum at the invitation of its curator, Carl Becker. When I last saw him, I had asked him to be on the lookout in the dark recesses of his building for a companion portrait of Andrew’s first wife Sarah Anthony Morse Borden, Lizzie and Emma’s mother. It was my understanding, after speaking with Len Rebello (author of the seminal Lizzie Borden Past and Present), that such a piece most surely must exist. And if Luther’s had the Andrew, I reasoned, they were sure to also own the Sarah.

Near the end of last year, Len pointed me in a new direction, and one for which I will forever be grateful, as this new avenue not only confirmed the existence of the Sarah portrait, but led me to believe that there were even more riches in store in Swansea, Massachusetts, the summering home to the Borden family.

In conducting the research for his book, Len had found some handwritten notes by a former Swansea historian. They didn’t make it into his publication because by the time he came across them, his book was in its final edit. So he did the gentlemanly thing and shared his research with me, knowing that I was on a quest for the companion image.

The notes proved an exciting read. Not only had the writer made a list of all the Borden family items that the Swansea Historical Society had in their possession, but also she offered a detailed location guide to each artifact. After tracking down the original lists, I began the process of trying to ascertain just what was left and where it now might be housed. Unfortunately, the town historian’s home burned down years ago, which, sadly, claimed her life, and many of the Borden pieces were lost in the fire. It seems she was storing some Borden items in her home for safe keeping, never imagining that her home would be destroyed in a conflagration.

Borden items forever lost included a painting owned by Lizzie titled “Ponies of the Prairies,” an onyx stand with brass trim, an onyx pedestal, 6 fruit knives, a book titled “A Doctor of the Old School” with Lizzie’s signature, a Venetian glass syrup jug (“delicate green and carved”), and three pages of birth, marriage and death records torn from the Borden Family Bible.

As a good historian will wont to do, the Bible pages had been photocopied and added to the Swansea collection, so we at least can see them. The original leaves, alas, are no longer extant. The location of the Borden Bible is not known, but in 1968 it was thought to have been in the hands of Hamilton Mason Gardner, nephew to Orrin Augustus Gardner, who was recorded as having had possession of the Bible at his death in 1944.

Of interest to me is that on the “Deaths” page of the photocopy are notes by the Swansea historian that say that Orrin Augustus recorded the last four entries. He incorrectly lists the dates of death of Abby and Andrew as August 2, 1892, and of Lizzie as June 2, 1927. His good friend Emma Borden, however, he correctly lists as having passed away on June 10, 1927. Of all the Borden clan, Emma would be the one that Orrin would get right, as she was a visitor to his home in Touisset, named “Riverby,” he called on her many times in Newmarket, New Hampshire, and, on Emma’s death, she was waked in his home. Orrin also came into possession of many of her belongings “and had much to do with administration of her estate.”

Orrin’s connection here is vital to the story of how Swansea came into guardianship of the treasures I would uncover, as he donated a good portion of his belongings and photograph albums to the Swansea Historical Society upon his death. They were given to the Society by his nephew, Hamilton Mason Gardner, and are so marked and numbered.

Among the handwritten notes penned by the Swansea historian, one finds the proof that a Sarah portrait was made at the same time as the Andrew, as it lists the two pieces residing in the society collection. These eventually found their way to Luther’s Museum and there they sat all these years, until one determined scholar, who was hot on the trail of history, inspired a curator to go hunting with her.

Family Reflections

All in all, I made almost a dozen trips to Swansea in 2007 to track down leads, interview people, and search through document and photograph boxes and albums. I must know now as much about the contents of the Swansea Historical Society, and where everything is located, as any of its members! I exaggerate I know, but when I handled the papers and images, holding history in the palm of my hand, I gained an increased appreciation for pack-rats and folks who don’t throw family mementos and papers away. But, at the same time, I am screaming out under my breath, “Oh why aren’t these photos marked with names?” It is as if most of the past is slowly pulling away from us, as the older generation is passing away—a generation that might recognize some of these faces and name them for posterity. If I had to guess, I would have to say that less than half of the photographs in the Swansea Historical Society’s collection are identified.

It was while examining the photographs in the “Unidentified” archive box that I came across a familiar face. In one large photo, there is a group of fourteen men, eight standing, six sitting. It was here that I spied him. I let out an audible sound, something between a cheer and a laugh, as before me was the face of John Morse. Oddly, the part in his hair was on the opposite side of his head, but that can easily be explained by the common mistake made by portrait photographers in printing some images reversed.

Among this assembly of gentlemen is a black man, which should aid in the identification of its individual members and their connections to one another. In addition, there are three other “Morse-looking” men in the grouping, relatives of John no doubt. Morse was a Swansea name, and the Morse-Gardner connection, already researched prior to these expeditions, contributed to identifying these people.

On several subsequent visits, and with the permission of the president of the society and the curator of Luther’s Museum, I was given as much time as I desired to examine their holdings. Two such visits I made with Len Rebello, and we plan to return again in the spring, once Luther’s has reopened for the season.

Carl Becker called me to meet him at Luther’s one cold and snowy morning in December. He slyly hinted that he had found something “most interesting” at the museum and if I could make it over there, he would meet me in twenty minutes. Len Rebello, Michael Brimbau and myself dropped everything when he phoned. We were not disappointed.

As we climbed the stairs to the second floor with anticipation, I knew what lay ahead of me, but never expected the sheer beauty of what I would see. There she was, Sarah Anthony Morse Borden, looking lovelier than I had ever seen her. No wild-eyed stare, no hard years upon her, no hint of sickness that would claim her in her 40th year, only the soft round visage of a woman who was in her prime. She looked happy.

And it was great to see them together—Andrew and Sarah—for theirs was a 17-year-marriage that only ended because of her death, less than three years after the birth of their last child, Lizzie Andrew.

Carl had also found an oval gilt-framed hand colored portrait of an older woman in banana curls, which he thought was part of the grouping. Since the woman is unidentified and no one to date knows who she is, and she is not listed as among the Borden portraits owned by the society, it is possible she is not from the same family. The frame is different in significant ways, but the Andrew and Sarah frames are identical.

While photographs were being taken of the portraits, I went poking into the book room, where I had originally found poor Andrew leaning against the wall under the window. I eagerly started looking through each book, hoping I would locate more marked in Orrin Gardner’s hand, like the ones I had seen on my first visit in August. Not to be disappointed, for Luther’s Museum never disappoints, I did find several more books from Orrin’s personal library, and a few other startling discoveries as well.

There, amongst the book collection housed in antique barrister bookcases, I stumbled upon another name I recognized—Emma L. Borden. So Orrin had indeed inherited quite a number of Emma’s possessions, and now they had found their way into my hands, as if passed directly from Emma to me. As each title was unearthed, I shouted, “found another one!” and brought it to the group in the other room, to be photographed and digitally recorded. I located six titles in all—The Ruined Abbeys of Scotland by Howard Crosby Butler (1899), Constantinople Vols. I and II by Edwin A. Grosvenor (1895), The Dictionary of English History (1885), volume one of Lorna Doone, and an 1864 copy of The Sixth Reader—but I am sure there are more. Carl knows I will be back to help catalogue the collection’s ownership marks during my Spring Break. While others come to Florida for their vacations, I travel to Fall River to volunteer in museums!

Carl said he could no longer feel his toes and that there would be more to discover at another time. I was reminded of my father saying to me, when I stayed too long at the fair, “It will come again and we can go again, but let’s not overdo it and ruin the fun.” I guess I have not outgrown that little girl who gets so involved in what I find pleasurable that I become oblivious to the suffering of others. I would call that focused. Others might call it something less positive.

The Swansea Historical Society had more surprises in store. With Len by my side, or should I say, me by Len’s side, we revisited the collection where I had found the Morse. We were both determined to ferret out everything we could find, but that work would take several visits.

It is a little complicated, but this is how the society came into possession of so many of Orrin’s effects, according to notes found in the society’s collection. Emma Borden bequeathed to Orrin Augustus Gardner the sum of $10,000 “and all of my household furniture and furnishings, including all books, pictures, ornaments and personal effects not otherwise disposed of in this will, if he shall survive me.” Orrin lived in his father, Henry Augustus Gardner’s home, Riverby, in Touisset. As Orrin never married or had any children, when he died in 1944, the society was given some of his effects by Orrin’s nephew, Hamilton Mason Gardner—items from the Henry Gardner home. “Informative data” notes kept by the Swansea historian state that “Many books were given to the Historical Society by Hamilton that belonged to the Borden sisters. What was not disposed of by Hamilton to probate buyers, was sold to one Bailey, who kept a second hand store, on west side of North Main St., Fall River, (E. S. Brown Dept. Store Annex) for $25.00. I believe this lot consisted of Gardner pieces and probably some Borden pieces. I did not know all of what [Orrin] Gardner received in line of furniture from the Borden Est., so could not be sure, which of the two owners, Borden or Gardner, owned the various articles that were sold privately by Hamilton, and to Bailey.” Some pieces in the society’s collection are marked from the Henry Augustus [Gardner] Estate. So when it is said that Orrin donated items, it means that he was the last owner of them, but he never physically handed them over to the Swansea Historical Society.

An interesting non-photographic artifact is a scrapbook that is marked as coming “to the Swansea Historical Society August 23, 1945 from the Estate of Henry A. Gardner. . . The handwriting in this scrapbook,” the librarian in 1979 wrote, “was compared by me with that of letters of Emma and Lizzie in the possession of the Fall River Historical Society. The handwriting is definitely not Lizzie’s which is decisive and slanted to the right. It is probably Emma’s since many letters were markedly similar in the scrapbook and the letter. The inscription in ink ‘To Lissie’ on the front page of the scrapbook would further bear this out.”

This scrapbook is a series of handwritten entries, copied from various dated sources—newspapers, magazines, poetry books, etc. Perhaps if the content were to be compared with the text of the Sixth Reader found in Luther’s it might prove fruitful, and further identify the hand as that of Emma.

Part of what Hamilton gave or sold to the society were some of Orrin’s collection of family albums. The society owns nine of these albums, each of varying size and thickness. Each is marked “1 of 9,” “2 of 9,” etc. To date, three of the volumes are missing, and may be found yet, squirreled away in Luther’s Museum. But what is there is an amazing collection of genealogical significance. For the first time, we can put faces to the names we are studying, and can recognize the family resemblance before we even read the identifying names printed above or below many of the images.

The images that are marked include: Orrin Gardner, Preston Hicks Gardner and his first wife Abby Arnold, William Morse, Susie Morse, William Mason and his wife Amanda Gardner Morse, William F. Gardner, his wife Henrietta and daughter Gertrude, William Augustus Gardner, George Gardner and Syliva Pearse Gardner, Dr. Charles and Mrs. Gardner, Nathan Gardner, William Wilson Gardner, Mr. & Mrs. George Buffington, and Hannah Gardner.

Len and I took turns looking at the albums, first me then him, so we wouldn’t influence each other in case we found someone important to the Borden murder case or family. We found several gentlemen that looked very much like John Morse, but we could not be sure if they were he or relatives. We found a gaggle of Gardners, a mass of Masons, a variety of Vinnicums, and a multitude of Morses. And then we found “album 6 of 9”—or as Len and I like to refer to it, the Holy Grail.

It is a stunning little treasure, measuring roughly 6 inches by 5 inches, large enough to hold but one cabinet photo per page. On the inside cover is written in a cursive hand, “Probably belonged to Emma and Lisbeth Borden. Their property came into possession of Orrin A. Gardner.” It is stamped “August 23, 1945, Swansea Historical Society, Inc.,” and is additionally marked in handwriting, “Henry A. Gardner Est. Album #6 of 9.”

The first two cabinet photos are of Andrew Jackson Borden and Sarah Anthony Morse Borden. The image of Andrew is the later one than that which is depicted in the portrait found at Luthers, but the photograph of Sarah is the same likeness of the larger matching portrait.

Included in this album are 42 images, almost all unidentified. Even the images of Andrew and Sarah have been marked by a later hand. It appears that a previous historian attempted to identify several of the people, and those names are indicated on the inside rear cover. One image that had been marked above as “Williams” had been removed with a note stating it was given to the family who identified the person as their relative. Another photograph is of Charles Stratton, his wife Lavenia and their baby. If the name sounds somehow familiar, it is because these are the real names of Tom Thumb and his wife. The Strattons lived in Middleboro, near Fall River, and finding cabinet cards of them in family albums of the area was not as uncommon as one might think. They were available for sale and could be purchased inexpensively.

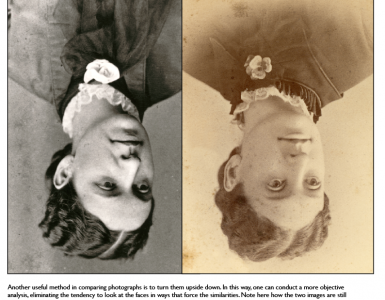

Near the back of this remarkable little wonder is an image that Len and I believe to be Emma as a child. We present it to you here for your consideration. In fact, when we first saw the image, separately, we both had the same gut feeling that this is she.

In another book entirely, we found the best of the lot. Without any marks or identifying notations, unassuming and undiscovered, we found our Lizzie—the image that graces the cover of this journal.

After all these years, it is glorious to have a new Lizzie face to peer into, and to play the game of trying to read her thoughts as the camera captured her likeness. With each new photographic discovery, we are slowly filling in the blanks of Lizzie Borden’s life. Including this photograph in the count, we now have nine Lizzie’s to ponder. Nine different ages, nine different outfits, nine different poses, nine different enigmatic views into the soul of a person who may or may not have brutally murdered two human beings.

My optimistic nature tells me there are more Lizzie photos in the world—and given time, determination, and serious scholarship, I am certain we will get to know her life and times better than we do now. I am confident that she is out there, waiting for us to recognize her in a crowd, on a train, or in a cabinet portrait or a brownie snapshot, in some collection, just waiting for us to bring her into the daylight.