by Stefani Koorey

First published in August/September, 2007, Volume 4, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

It was long assumed that Emma had spent her missing months at a female seminary. Mount Holyoke was the first best guess of Lizzie Borden scholar and author Len Rebello. But it wasn’t until Kristin Pepe, Laboratory Director in the Psychology and Education Department at Mount Holyoke, launched her own investigation that she came up with the golden ticket when Wheaton College confirmed that Emma had indeed attended there. Now let’s get Kristin onto finding Bridget Sullivan’s inquest testimony, the real name of Todd Lunday, and the murder weapon.

All Wheaton archive images courtesy of Marion B. Gebbie Archives & Special Collections, Madeleine Clark Wallace Library, Wheaton College, Norton, Massachusetts.

Emma Lenora Borden attended Wheaton Female Seminary, in Norton, Massachusetts, from April 1867 until July 1868—four semesters in all—starting when she was but 16 years old.

Although Emma did not graduate from this four-year program of study (and few who went to Wheaton during this time did), she was exposed to the full range of the female seminary experience.

Like all students, Emma attended daily prayer meetings in the boarding house, and church every Sunday at the Trinitarian Congregational Church, which still stands today. She was not allowed to receive packages from home to make her stay there any different from any other girl. An official list specified what each student was required to bring, including clothing, a pair of sheets and pillow-cases, towels, napkins and napkin ring—all marked with the owner’s full name. Students could not correspond with anyone they were not related to, unless their parents had provided those names to the Principal.

Every minute of a young girl’s life was regulated at Wheaton, with 31+ bells demarcating the day—from awaking in the morning at 5:45 am, to retiring at 9:30 pm. Student Elizabeth Morville recorded these schedules of times in her 1850-51 diary. The time notations here have been modernized:

5:45 – RISE

6:30-7:00 – HALF HOUR OUT [roommate’s private devotion or study]

7:00-7:30 – BREAKFAST

7:40-8:10 – HALF HOUR IN [private devotion or study]

8:15-8:45 – STUDY LATIN

8:45-9:00 – PREPARE FOR SCHOOL

9:00-9:30 – DEVOTIONS [including all students & teachers]

9:30-11:30 – STUDY WAYLAND. PALEY.

11:30-12:00 – READING OR MUSIC

12:00-1:00 – DINNER

1:00-2:00 – RECREATION OR STUDY

2:00-2:30 – RECITE WAYLAND.

2:30-3:00 – STUDY

3:00-3:20 – CALISTHENICS

3:20-3:30 – RECESS

3:30-4:00 – RECITE PALEY

4:00-4:30 – RECITE VIRGIL

4:30-5:00 – RECREATION

5:00-6:00 – SUPPER

6:00-6:45 – RECREATION

6:45-7:00 – PREPARE FOR STUDY

7:00-8:00 – STUDY HOUR

8:00-8:30 – HALF HOUR IN

8:30-9:00 – HALF HOUR OUT

9:00-9:30 – STUDY HOUR

9:30 – RETIRE

A student in 1875 recorded a list of sixteen “Rules and Regulations of Wheaton Seminary” that ordered a young woman’s life during her seminary years:

Rule I. Pupils must not go to the Post Office without permission.

Rule II. Promptness in everything is required of the pupils.

Rule III. Rooms are to be visited only in recreation hours.

Rule IV. Teachers must not be interrupted in study hours except in the case of necessity.

Rule V. Pupils under 18 years of age are not to go to the store without permission.

Rule VI. All must keep Cash Accounts.

Rule VII. Must not go riding without Mrs. M’s permission.

Rule VIII. Can’t go ride without permission from home.

Rule IX. No gentleman callers who do not bring letters of introduction are received.

Rule X. Must not answer the doorbell.

Rule XI. No one to go out of their room to sleep without Mrs. M’s permission.

Rule XII. Pupils do not receive their gentleman friends in their bedrooms.

Rule XIII. Must not talk in the library.

Rule XIV. Not to talk from windows.

Rule XV. Nothing to be thrown from windows.

Rule XVI. Must not borrow money or wearing apparel.

The Sabbath was strictly kept and no one, including parents, was allowed to visit the school on Sundays.

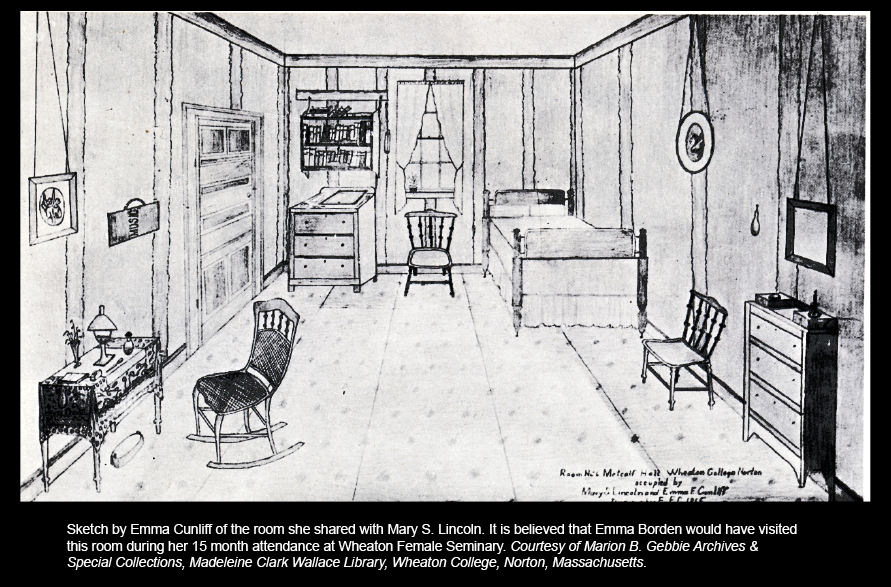

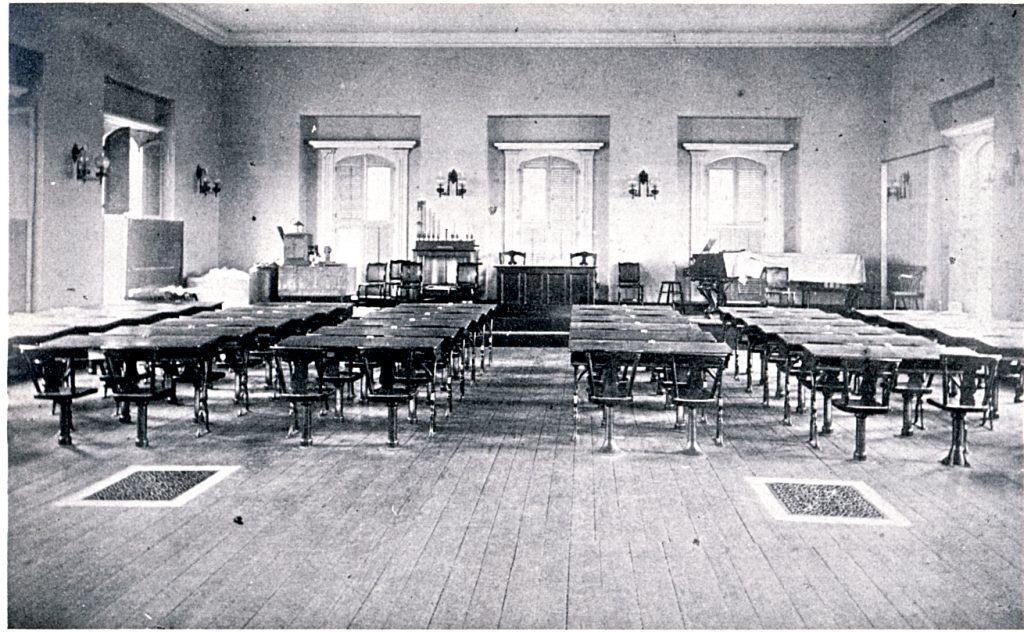

Emma lived at the school, boarding with a roommate, although we do not know who this was. Most personal records, such as letters of application, have not survived and room assignment records are only available from the mid 20th century onwards. We know that Wheaton’s boarding house could accommodate housing their teachers and ninety-five pupils, the others housed with families in Norton.

Privacy was at a premium and girls were granted only two half-hours alone in her room each day, expressly for religious prayer and devotion. While sparsely furnished, each student’s room averaged fifteen feet by twelve and contained two bureaus, wash stand, pitcher and basin, a bookcase and a table. The bed was a double, and it wasn’t until the 1880s that female seminaries switched to single beds. The 1866 sketch by Emma Cunliff of the room she shared with Mary S. Lincoln details the living conditions there. Wheaton College Archivist Zephorene Stickney is confident that Emma visited this room, as Emma was at Wheaton while both Cunliff and Lincoln were enrolled, and when the sketch was made.

In the school year ending July 1868, there were a total of 157 pupils enrolled at Wheaton, with 122 attending the Fall semester, 101 the Winter, and 110 in the Summer. 86 pupils took French, 25 studied Latin, 25 studied Drawing, 2 took German, and 8 were enrolled in the Normal school (teacher education). Ages of the students ranged from 13 to 25, but the younger girls were mostly local Norton residents who lived at home and did not board at Wheaton.

When Emma attended, she was one of six young women from Fall River. In her Junior Middle class were Laura W. Anthony, Kate H. Remington and her sister Sarah W., and Adelaide M. Brightman. In the Senior Middle class was Martha C. Brigham.

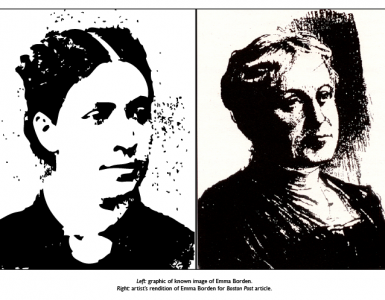

Unfortunately, as of yet, no photographs of Emma at Wheaton have surfaced. Since she did not finish her education, it is doubtful whether she would have appeared in any group photographs, which were usually reserved for those who completed the full course of study and graduated.

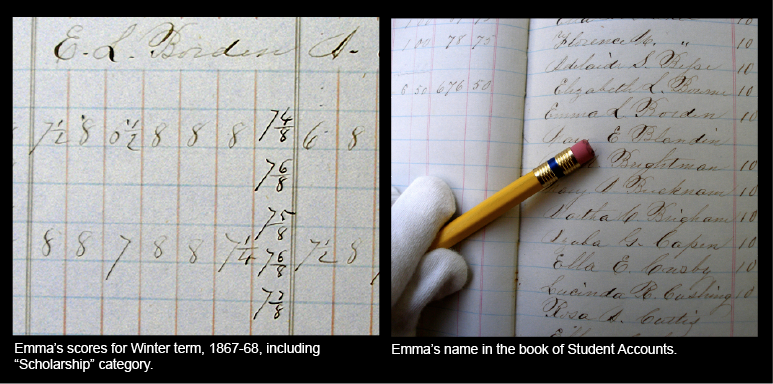

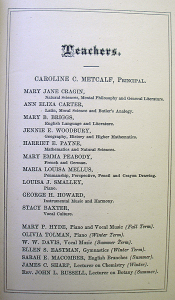

What does exist are Emma’s grades and her Student Accounts, which detail how much Andrew Borden was charged for his oldest daughter’s stay and study at the school. We also have a list of her teachers and their images, and a complete list of the textbooks used in the classes she attended.

These documents are telling in that they open up a window onto the world of the post Civil War era educational system, and seminary life in Massachusetts in particular.

Grades at Wheaton were recorded in a Semi-Monthly Report for each semester and a copy of each young woman’s report of deportment and scholarship was sent to her parents or guardian twice a month. A year at Wheaton encompassed three semesters: Fall, which ran from early September until late November; Winter, which ran from early December until mid March; and Summer, which ran from early April until early July. It appears that there were no classes during the month of August.

Grades were awarded in number format, with no one receiving greater than an 8, although it is believed that the “perfect” score was a 9. According to Wheaton archivist Zephorene Stickney, “In the Victorian Era it would never occur to any teacher that a student could possibly earn a perfect grade. There would have been some flaw in penmanship or structure or grammar.”

The rating system is somewhat of a mystery, as numbers such as 7 ⅜, 7 ⅝, and 7 ⅞ sometimes appear. On the Semi-Monthly Report, the scores were given for “Order of Room” (which indicated that teachers inspected student rooms on a regular basis), “Order of Wardrobe,” “Care of Health” (which included physical exercise such as walking and gymnastics), “Promptness,” “Accuracy of Accounts,” “Deportment,” and “Scholarship.”

Emma’s grades show scholarship points for only the Winter term of 1867-68, her third at Wheaton. She scored between 7½ and 8 for each mark listed. For other areas of grading, Emma was only consistent in one category, “Order of Wardrobe,” scoring a perfect 8 for all 9 marks during her stay. Her weakest area was in “Care of Health”—her score descending to a meager 6 ½ on two occasions. Apparently, keeping active was a major emphasis at Wheaton, although many young women elected to forego their physical activity in lieu of more sedimentary pursuits.

Interestingly, Emma’s next weakest category was “Deportment,” only twice in nine grades during her four semesters did she score an 8.

Emma’s entered Wheaton during the Summer 1867 term, which occurred from April 9th until July 7th, as a member of the “Junior” class, equivalent to our freshman year.. She took the standard and required battery of courses in the “English branches, including Vocal Music,” that is, courses that were not taught in foreign or ancient languages. She also studied the piano.

According to Wheaton historian Paul Helmreich, the “English branches” at Wheaton were purposely comparable, and often identical, to those studied by men at universities during the same time, even to the point of using the same textbooks. The “English branches” included all subjects other than studio art, music, modern languages, and classical languages and literature. Courses falling under this category included Algebra, Ancient and Modern History, Moral Science, Plane Geometry, Logic, Moral Philosophy, Geology, Chemistry, Astronomy, English Grammar, Rhetoric, Natural History, and Natural Philosophy. A major expansion of Seminary Hall in 1878-79 provided additional space for physics, biology, and chemistry laboratories. Mathematics and Science were “resolutely pursued” throughout a student’s years at Wheaton.

Emma’s second semester (Fall term) occurred from September 5th until November 25th, 1867. Again, as in all her terms, she took the “English branches” courses, and added to her studies French and piano.

From December 10th to March 17th, Wheaton’s Winter term, Emma again chose to pursue French and the piano in addition to her “English branches” classes.

Emma’s last semester at Wheaton, the Summer term of 1868, which ran from April 3rd until July 8th, was different than that of Winter—she took her third piano class but didn’t enroll in French. She had advanced to the “Junior Middle” class, equivalent to the sophomore year.

We know the exact “English branch” classes taken during any particular term from the Thirty-Third Annual Catalogue of Wheaton Female Seminary, for the Year Ending July 1868. In addition to its lists of teachers and students in each class and language area, there is some back matter that offers us details regarding the typical Wheaton student’s “English branches” course of study. It states, “The regular course of study embraces four years, but the time required in each case must depend upon the age, capacity, diligence and previous attainments of the scholar. Pupils will be examined in branches already studied, and classified accordingly.”

First year, first term, students studied Arithmetic, Grammar, and Modern Geography. First year, second term, students enrolled in Arithmetic, Grammar, and History of the United States. First year, third term, students took Arithmetic, Analysis of the English Language, and Natural History.

Second year, first term students were enrolled in Algebra, Ancient History (including Ancient Geography), and Physiology. If Emma had stayed another two semesters at Wheaton to finish two years of schooling there, she would also have taken the second section of Algebra, History of the Middle Ages, and Geometry (second term), and the second section of Geometry, Modern History, and Botany.

It was common for families to enroll their daughters in the female seminary system for only a year or two, without plans to have them complete their education and earn a degree of any kind. A few semesters of school was enough to give the young ladies the needed tools to make a woman an able mate.

What else do we know of Emma’s Wheaton years? We know how much Andrew paid for her terms of study—and it was not an inexpensive investment in his daughter’s future.

The first semester Emma was at Wheaton, Andrew paid $87. This amount included $10 for “English branches including V. music,” $12 for Music, $3 for the use of the piano, $1.75 for “Incidental and Lib’ry Tax,” and $60.25 for Board, Fuel, and Lights.

The second term showed a slight increase in the total cost because Emma elected to add French to her program of study, and that course cost Andrew $5. Her fees for the “English branches” went down to $9, perhaps because she took one less class, but we do not know for sure. Her board, fuel, and lights were roughly the same, at $60. Andrew’s total bill for the Fall term, 1867, was $90.75.

Emma’s third term, Winter 1867-68, was her most expensive, setting her father back $109.25. For this semester, Emma’s board, fuel, and lights went up to $75, probably because the colder months necessitated more fuel. She once again added a $5 French class, and the luxury of renting a carpet for her room at $2.50. Carpets were often rented in the winter months because the floor’s surface was bare.

For Emma’s last term, Summer 1868, she again rented the carpet at $2.50, but did not enroll in her $5 French class. Instead, she studied the piano again and incurred the piano rental fee. The board, fuel, and lights were $70, making Andrew’s cost just under one hundred dollars, at $99.25.

For four terms of study at Wheaton, 15 months of education, Andrew paid a total of $386.25, not counting Emma’s pin money or extra purchases such as textbooks and supplies. Considering that Emma never married, perhaps Andrew later felt that his investment in her future had been a waste of money. However, it is safe to conclude, says Zephorene Stickney, that “based on the courses that Emma took, she was better able to handle the financial aspects of running a household, that she would have been a more informed conversationalist, friend and companion. Perhaps she could sing and play the piano better, and accompany herself and others, a major form of home entertainment at this period. Perhaps, also, the academic and religious education she received at Wheaton encouraged her charitable activities and church work.”

In 1912, Wheaton Female Seminary became Wheaton College. Today it is a well-regarded private coeducational four-year liberal arts college.

Works Cited:

Helmreich, Paul C. Wheaton College 1834-1957: A Massachusetts Family Affair. NY: Corwall Books, 2002.

Helmreich, Paul C. Wheaton College 1834-1912: The Seminary Years. Norton, MA: Wheaton College, 1985.

Thirty-Third Annual Catalogue of Wheaton Female Seminary, for the Year Ending July 1868. Pamphlet. Marion B. Gebbie Archives and Special Collections, Madeleine Clark Wallace Library, Wheaton College, Norton, MA.

“Semi-Monthly Report.” Marion B. Gebbie Archives and Special Collections, Madeleine Clark Wallace Library, Wheaton College, Norton, MA.

“Student Accounts: Summer 1866 – Fall 1880.” Marion B. Gebbie Archives and Special Collections, Madeleine Clark Wallace Library, Wheaton College, Norton, MA.

Editor’s Note: Shelley Dziedzic and I would like to thank Zephorene L. Stickney, College Archivist and Special Collections Curator, Marion B. Gebbie Archives and Special Collections, Madeleine Clark Wallace Library at Wheaton College, for her considerable knowledge and assistance in helping us locate the information contained in both essays.