by Leonard Rebello

First published in January/February, 2008, Volume 5, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

It has always been believed that Emma Borden gave an interview to Edwin Maguire of the Boston Post in 1913, one week following a story about her sister’s life appeared in the Boston Herald. Did she or didn’t she?

One week prior to Emma Borden’s 1913 interview in the Boston Post with Edwin Maguire, Gertrude Stevenson of the Boston Herald, published a lengthy account of Lizzie Borden’s life after the trial on April 6, 1913, titled, “Lizzie Borden Twenty Years After the Tragedy.” It was an extensive article accompanied by several illustrations. The Fall River Daily Globe and other newspapers were quick to run the story the very next day, perhaps realizing many local people may not have subscriptions to the Boston Herald and would be interested in Lizzie’s life and how she was faring in Fall River. After all, the Fall River Daily Globe had been reminding the general public of the Borden murder case since 1892 by publishing yearly articles implying Lizzie’s guilt and that the murderer may still be in Fall River. It was a campaign that Edmund Pearson, author of The Trial of Lizzie Borden (1937: 81), called the “annual feast of sarcasm” toward Lizzie Borden by city editor James Dennan O’Neil. It was a campaign to keep the Borden tragedy alive in the press and harass Lizzie Borden, who was acquitted in June 1893. It continued until 1914 and ended with the intervention of Father James Cassidy of Fall River. Father Cassidy later became a bishop in Fall River.

It appears competition among the Boston papers was fierce in 1913, as the Boston Post, one of the most popular newspapers in New England, was not to be outdone by the Boston Herald. The Borden case and Lizzie news attracted the public. One week later, on April 13, 1913, Edwin Joseph Maguire, a former bookkeeper and a young newspaper reporter for the Boston Post, published an interview he conducted with Emma Borden, now sixty-two. The interview took place in the former study of the late Rev. Edwin Augustus Buck (1824 -1903), among the well-respected clergyman’s memories of pictures and framed Biblical quotes. The Buck home on Prospect Street was but a short downhill distance from Maplecroft (“Guilty- NO! NO!’ Lizzie Borden’s Sister Breaks 20-Year Silence. Tells the Sunday Post of Past and Present Relations With Lizzie.” Boston Post, Sunday, April 13, 1913: 25).

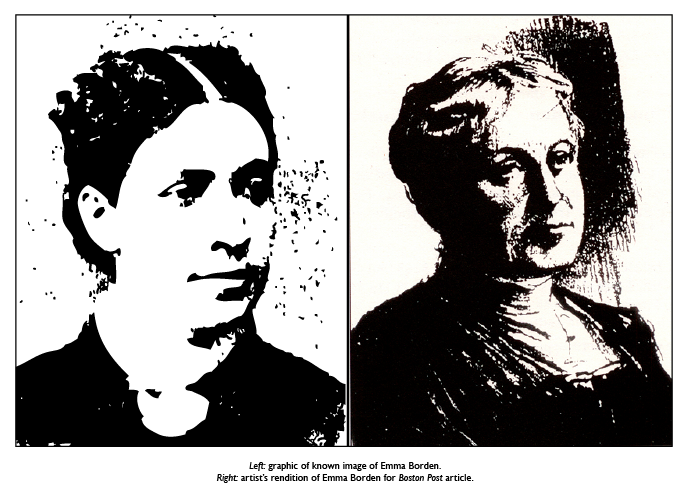

A sketch of Emma drawn from life by a Post artist accompanied Emma Borden’s interview reported by Edwin Maguire. The content of the interview has been quoted extensively over the years in much of the Borden literature, while others oftentimes suspected and even doubted that the interview occurred. The latter claimed Emma would never have granted such an interview after all her years of silence, especially with such revealing personal thoughts coming from a very private woman. She would have been aware of the publicity an interview would create. Perhaps there was no interview in 1913.

Why would Emma Borden, the quiet older sister, usually portrayed in newspapers as staid, gentle, meek, dignified, and reserved grant such an interview to a Boston Post reporter, especially to an outsider? Why a live sketch she knew would be wired across the nation? Why would Emma suddenly speak out to defend Lizzie after she separated from her in 1905? What generated or motivated the need for Emma to provide more support for Lizzie and address the “Maplecroft happenings” in such revealing and personal words? It was apparent that several “happenings” or “conditions” that occurred contributed to Emma’s leaving Maplecroft. But what were they?

The rumors, street level gossip, and newspaper reports about Lizzie prevailed over the years. There was the wedding rumor in 1896 that Lizzie was to marry a man from Swansea, where the Bordens had a summer home (Fall River Daily Globe, December 10, 1896: 8). In 1897, newspapers reported that the Tilden-Thurber Co. in Providence, Rhode Island, had a warrant issued for Lizzie’s arrest for shoplifting two porcelain paintings. A family member, and reportedly Attorney Andrew Jennings, Lizzie’s defense attorney, intervened and settled the matter. Two years later, Lizzie made the newspapers again in November 1899 when the Fall River Evening News reported a rumor that the Pinkerton detectives were shadowing Lizzie for shoplifting in Boston. Lizzie sent a note in May 1900 to Mr. John S. Brayton, a neighbor, saying she was “nervous,” and “cannot sleep,” due to the noise from a “little bird that crows so much at your house.” The police were summoned to the Borden house to attend to the youngsters from the “Hill” or the Highlands. They were running through the Borden property, throwing eggs at the house, ringing the doorbell at night, tying doors and calling Lizzie names when she answered the door (Fall River Daily Globe, May 9, 1902).

The Boston Herald (June 4, 1905) found the best reasons for Emma’s departure to be Nance O’Neil (1874-1965), the stage actress, and Joseph Tetreault (1863-1933; also Tatro, Tetrault), the chauffeur. What contributed to Emma’s leaving her younger sister, known throughout the world, in 1905 is speculative, but can be reduced to six possibilities:

(1) The story of the Tilden-Thurber shoplifting incident in 1897 and the warrant issued for Lizzie’s arrest, in the Providence Journal. This would have caused public attention toward Lizzie and perhaps embarrassment to Emma;

(2) Emma’s reported dislike of the position of the thirty-eight year old coachman at Maplecroft, Joseph Tetrault, a former barber, whom the Boston Herald described as a “fine looking young man and reported to be very popular among the ladies.” Lizzie employed him for six years beginning in 1901 until 1907. Two of those years (1906-1907) he boarded at Maplecroft. He was asked to leave because he was “distasteful to the elder Miss Borden,” but later returned to his duties at Lizzie’s request (New Bedford Standard, June 2, 1927:2);

(3) Lizzie’s reported “recent infatuation for stage folk and dramatic matters,” (Boston Herald June 4, 1905:11);

(4) The actress Nance O’Neil was appearing in Magda at the Cleveland Theater, New York, in October 1903, and in the last week of November in Detroit. Her intimate friendship with Lizzie reportedly began in 1904. Miss O’Neil appeared on stage throughout New England including Boston and Fall River, having appeared in several plays from 1904 to 1907, as sampled below:

January 1904 at the Columbia Theater in Boston in Fires of St. John;

February 1904 at the Colonial Theater in Boston in Lady Macbeth;

October 15, 1904, at the Tremont Theater in Boston in Judith of Bethulia;

October 20, 1904, in Fall River at the Academy of Music in Magda;

February 1905 at the Academy of Music in Fall River in Magda;

May 1905 at the Academy of Music in Fall River in Elizabeth the Queen;

December 1905 in Boston at the Tremont Theater in Judith of Bethulia;

September 1906 Nance O’Neil returned to Fall River and appeared at the Savoy Theater on North Main Street in Lady Macbeth. Her last appearance in Fall River was in 1907, January 3-4. Interestingly, the Academy of Music in Fall River faced the Andrew J. Borden Building owned by Emma and Lizzie and the Savoy Theater in Fall River at the end of Granite Street, a short walking distance from the police station where Lizzie’s inquest and preliminary hearing were held in 1892;

(5) Lizzie, and not Emma, began to purchase land around Maplecroft in November 1897 (the Kenney home in 1897 that was later removed), land behind the Swift home in April 1902 reportedly to add a driveway to the $3,000 garage, and land on the south side of French across from Maplecroft in September 1905. Emma may have not approved or agreed to these land purchases and expansion plans. Emma and Lizzie were engaged in several land transactions. They sold the old Borden house on Ferry Street in July 1896, sold land to the city on Spring Street in 1900, and obtained a right of way on the east side of the Swansea summer home in May 1901;

(6) Reasons that may never be known that caused Emma’s departure may stem from an unknown, undiagnosed and untreated spectrum of psychiatric, psychological or social/emotional disorders, a confession by Lizzie or Emma, or unacceptable social behaviors.

In 1927, Minna Littman, a staff correspondent for the New Bedford Standard, reported that Nance had entertained Lizzie for a few days in her country home in Tyngsboro in 1904. It was in May 1905 that Miss O’Neil appeared at the Academy of Music in Fall River in Elizabeth the Queen. Local reviews of her performance were quite favorable. Lizzie was also impressed and was reported to have entertained Miss O’Neil and the entire cast at Maplecroft after Nance’s performance. Miss O’Neil told Miss Littman in June 1927 that, “Reports that she had spent some time at the Borden home in Fall River, or that she had ever met Miss Emma Borden, she [Nance] characterized as in error.” It was after May 1905 when Emma left Lizzie and Maplecroft. It is unknown as to whether or not Emma and Lizzie did or did not meet or communicate with each other after Emma left. They may very well have corresponded by notes, letters, telephone, or through their attorneys, as both sisters continued buying, selling and leasing property they owned jointly from March 1907 until January 1927.

Whatever the accumulated reasons that caused Emma’s long thought-out departure, they would have had occurred between 1892 and 1903, as her spiritual advisor she consulted, Rev. Buck, died in March 1903. Newspaper accounts claimed Emma made her departure in 1905 only after she consulted and was advised by Rev. Buck. The “happenings” and “conditions” on French Street that so disturbed Emma seem to have started long before the theater people and Nance’s arrival in Fall River in 1904. Nance O’Neil was on a worldwide tour in 1902, appearing in several New York and San Francisco productions in 1903. She opened in Boston in January 1904 in Fires of St. John. Theater critics claimed that Boston could not get of enough of Nance O’Neil.

“In 1905 Emma Borden left her sister and made her home with friends, the action causing an estrangement between the sisters. Of this, Emma Borden said: ‘The happenings in the French Street house that caused me to leave I must refuse to talk about. I did not go until conditions became absolutely unbearable’” (“Lizzie Borden Dies; Her Trial Recalled . . . Stoutly Defended by Her Sister, Who Became Estranged From Her in Later Years,” New York Times, June 2, 1927:21). By October 1905, Emma and Lizzie signed an agreement as to Lizzie’s future financial responsibilities of Maplecroft which they continued to own jointly. Emma showed an interest in Scotland and Ireland, as a signed book of hers, Scotland’s Ruined Abbeys by Howard Crosby Butler (1899), was recently discovered at the Swansea Historical Society (December 2007). A three-volume edition of Ireland, signed in Lizzie’s handwriting, “1894, Emma L. Borden,” and the third volume signed “L.A. Borden,” had been among the Bordens’ library at Maplecroft and are now in a private collection. We know Emma was in Glasgow, Scotland, in July of 1906 as she sent a postcard from there. She returned to Boston on the S.S. Cymric, on October 14, 1906 (Boston Passenger Lists, 1820-1943).

Local newspapers reported Emma to be living in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, in 1905. However, no local directories listed Emma in Fairhaven or Rhode Island from 1905-1908. Emma resided in Providence from 1909, on the plush, well-to-do and well-connected east side of Providence with a relative, Preston Hicks Gardner, a banker, and his family, until 1913. Emma, according to city directories, was not listed in Fall River at the time of the interview. She may have moved in with the Buck sisters after the Providence directories were published. She was listed in Fall River in 1914 living with the unmarried Buck sisters and resided there until 1918, returning to Providence in 1919 to live in the exclusive Minden Apartments for nine years (1919-1927). Although her legal residence was in Providence, she frequently traveled to summer in Newmarket, New Hampshire from 1920 until her death in 1927.

Perhaps the reasons for Emma’s departure involved the 1897 shoplifting incident, the presence of Mr. Tetrault at Maplecroft whose position may have included more than being a coachman, those wild and free spirited theater people, and Nance O’Neil’s intimate friendship, all adding to the great divide between the sisters who, together, had faced an inquest, a preliminary hearing, a sensational murder trial, and of course the newspaper coverage around the world. Did Emma’s reported objections and departure in 1905 have a negative impact on Lizzie? Probably not, as Tetrault continued as coachman at Maplecroft for two additional years. Nance’s friendship went on for nine more years, according to Emma’s statement. Miss O’Neil continued with her career and went on to marry Alfred Hickman (1872-1931), an actor, in 1917. The theater people moved up and out; and Lizzie, for the first time, began using her new name Lizbeth (City Directories 1904-1905). Gertrude Stevenson, a newspaper woman, reported that Lizzie registered as Lisbeth Borden while at the Bellevue Hotel in Boston. Legal documents were signed Lizzie A. Borden while notes, letters, postcards, and books were oftentimes signed L.A. Borden and L. A. B. Emma left Maplecroft in 1905. Emma and Lizzie would be reunited at Oak Grove Cemetery upon their deaths in 1927; first Lizzie and then Emma nine days later.

The 1913 interview that appeared “circumstantially” contained more of what Emma may have wanted the public to believe as either true or untrue. Emma told the world that she agreed to look after “baby Lizzie” and be her sister’s “little mother” (a pledge she made to her dying mother on her deathbed), pay half of the trial costs, and “defend ‘baby Lizzie’ against merciless tongues,” and again declared Lizzie’s innocence. It was imperative that Emma reinforce Lizzie’s affection for pets and dotage on dogs, cats, and squirrels. How could an animal loving person kill her father and stepmother? We learn from the interview that Nance O’Neil’s friendship began in 1904 and continued until 1913. Andrew Borden was not to be remembered as frugal, cheap or “niggardly” as remembered in the community and reported in newspapers. These descriptors are perhaps misconceptions of the real Andrew Borden. Emma told Maguire that her father’s reported stinginess was not true, “That is a wicked lie. He was a plain-mannered man, but his table was always laden with the best that the market could afford.” According to Emma, meals served in August 1892 did not represent meals served throughout the year in the Borden house. Warmed-over mutton soup, fish, pears, cookies, coffee, and johnnycakes were staples the week of the murders. Is this the best Andrew’s money could buy in 1892?

“Every Memorial Day I carry flowers to father’s grave. And Lizzie does not forget him. But she generally sends her tribute by florist” (“Guilty- No! No! Lizzie Borden’s Sister Breaks 20-Year Silence,” Boston Post, April 13, 1913: 25). There was no mention of any Memorial Day remembrance for the almost forgotten Abby Borden, the stepmother and the first to be brutally murdered in 1892.

Emma, Lizzie, and the residents of Fall River were not able to escape twenty years of annual articles of the Borden murders. The Fall River Daily Globe was relentless with their yearly August 4th articles. These articles continued until 1914. Emma told the Post, “Just what the purpose of this practice is I do not know.”

There has been nothing to disclaim or even cast doubt as to the validity of Emma’s 1913 interview by Maguire until now. However, the day after the Post article was published, the Fall River Evening Herald published a startling denial that Emma granted an interview: “Post ‘Interview’ Denied By Friend Member of Buck Family Says Newspaper Story of Emma Borden Breaking 20 Years’ Silence Is Not Authentic.” It was the only local newspaper to report the denial of Emma’s Post interview. The Fall River Evening News, the preferred Yankee Republican-based newspaper, did not report the denial. The Evening Herald, considered to be non-partisan, wrote:

Although the above statement appeared circumstantially in the Boston Post of yesterday as part of an article purporting to be an interview with Miss [Emma] Borden, at the house where she [Emma] lived, it was said this morning by a member of the Buck family that it was not authentic (The Evening Herald [Fall River], April 14, 1913: 2).

Was Emma’s interview a media stunt? Was the young Maguire behaving like the modern day paparazzi? Did he seek Emma out and badger her until she finally agreed to the interview for the Post in the Buck’s parlor? How did Maguire know Emma was living in Fall River if she was not listed in the 1913 directory? Did Emma agree to the interview and then recant? It was well known in the Boston newspaper community that the Post, then owned by Edwin A. Grozier from 1891 until his death in 1924, was a progressive and savvy newspaper and known for creating publicity stunts. The most famous publicity stunt was in 1909. Well-crafted gold-headed “Gaboon” ebony canes were presented by the Post to several hundred towns in Massachusetts to be given to the oldest resident. Cities were not included and the tradition of presenting the canes is still carried on in towns. In 1911, Grozier assigned every reporter to the Avis Linnell murder case. The Post created a media sensation that lasted until Clarence Richeson was executed.

Who in the Buck family felt compelled as a “friend” to call or notify the locally known non-partisan newspaper to deny the interview? Did the Evening Herald contact the Bucks? The Fall River Globe was already biased and believed Lizzie guilty from the day of the murders. The Fall River Evening News supported the Bordens. Which one of the five unmarried Buck sisters living on Prospect Street notified the Evening Herald? Was it Alice, Clara, Eliza, Mary, a kindergarten teacher, or Nancy “Evy” Eveline, the well-known Fall River artist? Was it Rev. Buck’s son, Dr. Augustus Buck, who resided close by on Pine Street? The Herald never mentioned which family member notified them to deny that the interview took place. Whoever contacted the newspaper was more than likely prominent, well-known and respected in the community- perhaps a physician, teacher or artist. The Evening Herald was the chosen vehicle by the Bucks to report the denial to the public.

If the interview did not take place as claimed in the Evening Herald, then the sketch drawn from life of Emma by the Post artist was done elsewhere. The on-the-spot drawing of an older Emma in the Buck home may have been sketched from a photograph of a younger Emma Borden (see photographs) and redrawn to look like an older, white-haired woman.

The newspaper denial could have had potential legal ramifications for the popular New England Boston Post, Mr. Maguire, and the artist. There was no challenge from any of the newspapers or even Emma herself. Why did Emma keep her silence in 1905 and decide to speak out in 1913? Could a thirty-four year old newspaper journalist deliberately generate a fictitious interview to compete with the Fall River Evening Herald to sell or increase newspaper sales? It was one of the Buck sisters or Dr. Buck, and not Emma, who felt compelled by principle to deny the alleged interview on Emma’s behalf. Emma’s reported statements in that interview now become a challenge for future writers and Borden enthusiasts. The Evening Herald’s denial of Emma’s April 1913 interview achieved a veiled mystery of doubt.

SOURCES:

Newspapers, Magazines

Beales, Jr., Ross W. (undated). “The Boston Post, Gold-Headed Canes: Origins of Tradition,” Swansea Historical Society Files.1-4.

Boston Post, August 18, 1909 (Initial article telling of the canes distributed by the Post).

“Bothering Lizzie, Grown Boys and Girls Unwelcome Callers at Miss Borden’s,” Fall River Daily Globe, May 9, 1902:1.

Curry, Judy P. “Lizzie’s Enigmatic Acquaintance: A Closer Look at Actress Nance O’Neil,” Lizzie Borden Quarterly, Summer 1994: 4-5.

Eaton, Walter Prichard. “A New Theatrical Star: Nance O’Neil and Her Art.” Frank Leslie’s Monthly Magazine. Vol. LIX. 1904-April 1905: 564-566.

Flynn, Robert A. “Fact or Fantasy: In Defense of Nance O’Neil,” Lizzie Borden Quarterly, Vol. III, No. 4 October, 1996: 19.

Littman, Minna. “Nance O’Neil Recalls Lizzie Borden as Bearer of Devout Sorrow, Actress Sure Her Old Friend Was Guiltless. Tall Tragedienne Remembers ‘Frail, Little Gentlewoman’ Met in 1904,” (New Bedford Evening Standard), June 4, 1927.

“Lizzie Borden Left By Sister,” Boston Herald, June 4, 1905: 11.

“Lizzie Borden Is Dead of Heart Disease,” New Bedford Evening Standard, June 2, 1927:1.

“Lizzie Borden Dies; Her Trial Recalled,” New York Times, June 3, 1927: 21.

Maguire, Edwin J. “‘Guilty- NO! NO!’ Lizzie Borden’s Sister Breaks 20-Year Silence. Tells the Sunday Post of Past and Present Relations With Lizzie,” Boston Post. Sunday. April 13, 1913: 25.

“Nance O’Neil and Poetic Realism,” New York Times, December 4, 1904.

“Nance O’Neil, 90, Tragedienne of Stage in Early 1900’s, Dead,” New York Times, February 8, 1965: 25.

“New Role,” New Bedford Standard Times, June 5, 1927.

“Post ‘Interview’ Denied by Friend Member of Buck Family Says Newspaper Story of Emma Borden Breaking 20 Years’ Silence Is Not Authentic,” The Evening Herald [Fall River], April 14, 1913: 2.

Stevenson, Gertrude. “Twenty Years After the Borden Murder. Lizzie’s Life Since Famous Double Tragedy as Reviewed by a Boston Woman,” The Fall River Daily Globe, Monday, April 7, 1913: 10.

Books, Periodicals

Beasley, David R. (2002). McKee Rankin and the Heyday of the American Theater. Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfred Laurier Press. 352.

Clark, Tim. “Keepers of the Cane,” Yankee Magazine, March 1983.

Hall, Mr. & Mrs. S.C. Ireland: Its Scenery, Character, & c. (3 vol.). NY: A.W. Lovering, n.d.

Kent, David. (1992). Lizzie Borden Sourcebook. Boston: Branden Publishing Co, Inc. 329, 332, 345-6, 354-5.

Pearson, Edmund. Trial of Lizzie Borden. NY: Doubleday, 1937.

Rebello, Leonard. (1999). Lizzie Borden: Past and Present. MA: Al-Zach Press.

Young, William C. (1975). Famous Actors and Actresses on the American Stage. vol 2., NY: R.R. Bowker: 887-93.

Primary Sources

City Directories (Fall River, Massachusetts) 1900-1927

City Directories (Providence, Rhode Island) 1900-1927

Registry of Deeds (Fall River, MA) Land Transactions

Fall River Historical Society Archives (Emma sent a postcard from Scotland in 1906 saying there had been a lot of rain for two weeks).