by Michael Brimbau

First published in August/September, 2007, Volume 4, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

I had stopped to look over a friend’s damaged sailboat that rested on stands in his driveway on Freelove Street. It was tattered and derelict. The port, or left side, had a hole underneath the size of a football and the keel was cracked open like a hard-boiled egg and shoved up into the cabin. It was a sad sight. While out on a mooring, the old girl had broken free in a stiff blow and washed up onto the rocks.

I was about to crawl under the stern to inspect the rudder damage when a cell phone chimed behind me. Ah! You would be wrong to assume it was mine. After 30 years of working in telecommunications, I refuse to carry such a device. Before the ringer could sound again Stefani Koorey quickly answered it. The way she flung open the phone, I decided she must be either an enthusiastic Star Trek fan or a veteran cell phone user.

“Hello Mr. Miranda . . . ah yes, Michael’s looking at a boat—we should be there very shortly.” I bit the corner of my lip and squinted as the tide of guilt slowly streamed across my face. I knew we did not have time to stop and look at the old boat, but since it was on the way, I thought . . . well.

Our destination had been to connect with my childhood friend John Miranda, a teacher at Diman Regional Vocational Technical High School. John was kind enough to arrange a meeting between Stefani and Fall River historian Bill Goncalo. Bill, an English teacher at Diman, is an authority on the island of Interlachen, Col. Spencer Borden, and the ice industry in Fall River. I was delighted to have been able to get the two Borden scholars together.

Spencer Borden: A Brief History

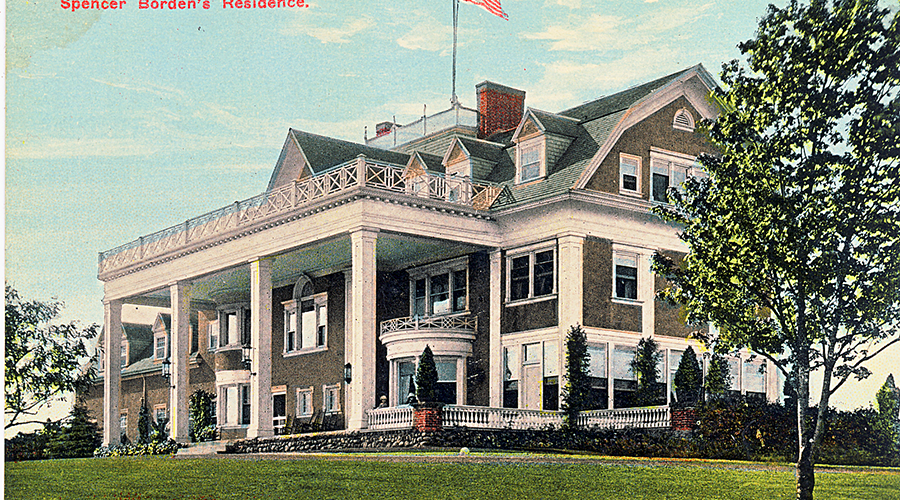

Interlachen was the location in Fall River, Massachusetts, of the opulent residence of industrialist Col. Spencer Borden—textile entrepreneur, pedigree horse breeder, and celebrated author. I grew up with the impression that its name was taken from an old American Indian expression. In truth, Borden had named his island home after a Swiss township in the German-speaking Alps, named Interlaken (from the Latin: inter lacus). The district of Interlaken lies over 570 meters above sea level and is nestled between lakes Brienz and Thun. This beautiful setting is one of the oldest tourist resorts in Europe. One can only guess whether Borden visited Switzerland and the Alps when attending school in Europe and walked away so impressed that he adopted the name Interlaken for his own, changing the spelling. Locally, in time, the term Interlachen took on its meaning: land between the waters.

Borden built his mansion home overlooking the North Watuppa Pond in the east end of Fall River. A peninsula jetting out into the pond, Interlachen truly became “between the waters” when the Fall River Water Commission raised the water levels of the pond, turning it essentially into an island. Around the turn of the 20th century, pond levels were manipulated to further plans for turning the north pond into Fall River’s primary source of drinking water. This meant separating the North and South Watuppa and regulating the flow of the North Watuppa, along with all its tributaries. To accomplish this, a careful study needed to be done, since both ponds were the primary source of the Quequechan River that ran most of the textile mills along its banks. In a further step, Fall River hired Arthur T. Safford, an engineer with a firm out of Lowell, Massachusetts. One of the many recommendations given by Safford to the Water Commission was for the city to condemn and then purchase all public and private land surrounding the pond. By eminent domain, the city began taking what land it deemed necessary. These actions placed Interlachen directly in the path of the entire project. Borden’s Shangri-la was unfortunately poised out in the middle of the pond surrounded by the very waters the city was trying to control.

Speaking about Borden at a gathering with a group called the Real Estate Owner’s Protective Association, Mayor John T. Coughlin claimed in effect, “the cultured gentleman from Ward Eight cared nothing for the people of this city.” While the city fought to exclude all trespass and gain complete control of the North Watuppa, Borden fought his own battle with the city and the local Board of Health for limited public access. To accomplish this, Borden proposed that the city issue seasonal licenses to boaters and fishermen. Coughlin had accused Borden of wanting control of the North Watuppa all to himself. Borden did not remain silent and in his own defense struck back fiercely. In a speech given to the same group some weeks later, he attempted to set the record straight claiming, “Any man, it makes no difference who he is, that says or said that I was looking for the exclusive privilege of fishing and boating on the North Watuppa Pond, is a liar.”

Further, after his preliminary study in 1909 was completed, Safford made nine recommendations to the Fall River Reservoir Commission. One of these was targeted directly at Borden and Interlachen. It stated that: “The Spencer Borden house at Interlachen, although having an arrangement for the disposal of sewage, may sometime prove to be a menace and ultimately should be controlled by the city of Fall River.” With tough language such as “menace” and “should be controlled,” one can see how a simple proposal can be worded to sound like a personal attack or a tinge of threat.

Thus continued an exasperating and perpetual feud between Borden and the city of Fall River. Unlike water, which flows down hill, power usually flows up, and Borden had plenty of it. His influence was earned partially by his wealth and in some measure by working for the governor, serving on his staff in the early 1890s, where he earned the title Colonel. Though the city went after other properties bordering the pond with virtually overwhelming success, no one dared challenge Alderman Borden directly, legally, or otherwise, with an ultimatum to give up his island paradise.

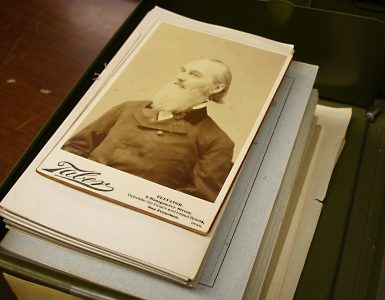

The Borden clan in Fall River had always been an influential bunch and Spencer was no exception. Though the Borden line goes back much further, part of the success and failures behind the family story can be traced back to two brothers, Thomas and Richard Borden. Spencer’s grandfather Thomas was patriarch to what Fall River historians like to describe as the “Greater Bordens,” a long lineage of wealth, privilege, and authority. Jefferson Borden, Spencer’s father, was agent for the Fall River Iron Works Company and later became executive officer for the giant American Print Works. This poised Spencer firmly on the prosperous limb of the Borden family tree. Being fortunate enough to attend university in France, where he honed his trade, he graduated in 1870 and returned to Fall River. Two years later he went on to establish his own business, the Fall River Bleachery, near the shores of the South Watuppa Pond.

Success abounded on the Spencer side of the Borden family tree. Just as accomplished, and perhaps more so, Spencer’s older brother, Jefferson Borden, Jr., is credited with bringing electricity to the textile mills in Fall River. Their cousin, M.C.D. Borden, who lived in New York and married into the powerful Durfee family, went on to become one of the wealthiest of the Borden clan. M.C.D. built the largest textile conglomerate in the world and tied the mill industry in Fall River with corporate interests in New York City and the rest of the world. Though Spencer’s father, Jefferson Borden, developed serious financial difficulties of his own later in life, the successes more than outweighed the failures.

While Spencer’s grandfather, Thomas, pulled all the right levers, Richard Borden, Thomas’s brother, died bankrupt. Unfortunately, Richard’s claim to fame is being grandfather to the branch of “Lesser Bordens.” Most of his offspring became laborers and farmers. This included Abraham B. Borden, Lizzie Borden’s grandfather. Though Federal census records show Abraham as a laborer, he probably had many vocations. While historians tend to label Abraham a miserable failure, describing him as a fishmonger or eccentric street peddler, there is no proof that these were his primary or only occupations—though he probably sold fish at one time. Abraham was purported to be well liked by most who knew him. I believe many Borden littérateurs and armchair historians have unfairly singled him out as a disappointing failure in a shoddy attempt to bolster his son Andrew’s success.

Interlachen—The Journey Begins

It was the end of the day as we drove into the school parking lot. There we met John where he introduced Stefani to Bill. After salutations, smiles, and handshakes were out of the way, we all clambered into my pickup and were soon on the road. The short drive took us to the end of New Boston Road. At one time, before the construction of RT 24, New Boston Road extended onto Interlachen. Today, we needed to find other ingress onto the island. Not far away, I tucked my vehicle off to the side of the road. A couple of feet further was an overgrown wooded area with a path or road barricaded by a rusty chain link fence. Here Bill revealed to us a back way onto the island to the west shore of the North Watuppa. The only road to this area is at the end of Bedford Street, through city property, along land belonging to the Water Department. Fall River is very guarded and somewhat obsessive about protecting its drinking water supply. Intruders are aggressively challenged and not allowed anywhere near the North Watuppa without special permission. Bill, who has given tours of the area in the past, has the city’s blessing to wander the island and pond with notice. Still, as we circumvented the old chain link fence to the forbidden road which led to Interlachen, memories resurfaced of when I was a child, and the many fences I climbed, trespassing or cutting across somewhere I did not belong. This time was just as much fun.

With a red windbreaker tied around his waist, notebook in hand, and tan running shoes, to some, Bill looked more like a senior in college than a high school teacher. Tall and slim, and looking barely into his thirties, he appeared as eager to escort us on our little tour as we were to attend—well almost as eager. My impression of Bill was of an introspective naturalist, a man in love with nature, history, and open space. Not long into our walk I realized this was an individual doing what he loved—teaching local history free from the restraints of the classroom, amongst the trees, along the water, kicking up the soil. I felt fortunate to be on this private tour sharing my interest in Interlachen, and all things Borden, with others who held the same historical interest.

The weatherman had declared the threat of rain, but the afternoon turned out somewhat overcast, yet dry. Approaching the causeway, a narrow land bridge between the mainland and island, we all eagerly shadowed Bill as if he was the Pied Piper. The old shrinking tar-paved road, once a continuation of New Boston Road, now lay fractured and overgrown with weeds. In the distance, a group of deer rustled through the briers, grazing, before dashing off after discovering our presence. Nature was all around. John walked ahead pointing out the diverse fauna and flora, including apple trees, raspberry bushes, even a scarce healthy elm. Stefani followed close behind, camcorder welded to one eye, keeping record of the day’s events. I also trailed a bit, my Canon in hand, snapping photographs. Looming up ahead, several hundred feet away, lay the ruins of the Cook & Durfee Ice House. It skirted the shore of the North Watuppa like the crumbling remnants of a medieval castle. Bill flipped open a black notebook and the lesson began. The 19th century stone ice house, along with the scenery, took on new life through the photos that Bill displayed. The ghosts of buildings, barns, and once-open fields materialized in our minds as we compared the 100-year old images to the forested landscape around us.

At the end of the byway, our intrepid guide trudged down an unmarked path through early spring undergrowth as we followed like a string of ants. We circumnavigated the old ice building and what appeared to be 50-foot tall free standing stone and mortar walls. The wooden timbers that capped these ancient storage spaces were long gone, which left the cathedral-sized interior overgrown with trees and brush. Bill was quick to surrender all he knew about the ice industry in Fall River as we bombarded him with inquires. “My father first told me of this place when I was just a kid. He’s the one that got me started, interested in the ice industry,” Bill continued proudly. “I love the natural ice industry. It’s lots of fun to research.” He stepped back and examined the scale of the building’s stone walls. “It was a very short-lived industry—it came, it flourished, and it tapered right off with the development of refrigeration.”

Every step we took relinquished new discoveries, whether it was the strange elongated openings in the walls of the ice house, or the granite stone foundations and walls that littered this isolated island. With every step, Bill was the consummate historical guide and tutor.

Across the narrow road from the ice house stood the ruins of an old granite foundation now flooded by the high pond levels. The central 8 x 8 Fall River granite columns protruded from the shallow water like abandoned cemetery plot markers. “This was once an old horse barn,” said Bill. “Here the ice company kept their horses.” Bill examined the floor below the foundation and showed us the location of the barn on a diagram in his notes. “The pond is at its highest level since I can remember. As you can see, it has flooded out this area which is much lower than the road.” Though the Cook & Durfee Ice Company owned a small portion of land at the very entrance to the island, most of the remainder of the island was Borden’s roost.

There is very little evidence left of Interlachen’s heyday. One must look at old photos or have a vivid imagination to envision the splendor that once graced this wooded terrain. Interlachen is now essentially forest. In the late 19th century, it was made up of rolling hills and barren fields, divided by well kept roads, a patchwork of finely built stone granite walls, and white ornate fences and gates.

Old Spence was an avid horseman. He began by raising Morgans and Polo ponies. Later, he went on to breed and race Arabians and became one of the leading authorities on Arabian horses in the country. He authored several books on horse breeding and care, including What Horse for the Cavalry and The Arab Horse, which is still in print to this day. Borden’s homestead served as a stud farm and sanctuary for these exotic and prized thoroughbreds. Many of these royal animals were imported from overseas. His estate was a virtual English garden and gentleman’s farm, which included bulls, oxen, and even turkeys. Among the exotic shrubs, flowers, and trees, Borden had constructed an island manor unlike anything ever built in this blue-collar mill town. Though Interlachen could be considered out in the country, it was still only minutes away from the downtown business district. As Bill described it, “When most of the affluent and successful corporate professionals in Fall River were building their sizable homes in the upscale and fashionable Highlands, Borden preferred the open country.” He looked down to his notes and smiled. “Spencer Borden followed a different drummer. Interlachen was far from busy inner city life, yet only a short ride away from his dealings with the corporate world and the mill industry in town.”

More recently, Bill Goncalo has been working on an ancestral study of the Spencer Borden family. He has traveled long distances to interview grandchildren of Bordens still living. In doing so, he has come away with captivating accounts and first hand anecdotes of family life at Interlachen in the early 1900s. If not for the spirited services of such personal studies, a rich and vital part of Fall River’s past and Borden family history might be lost forever. It is through the efforts of researchers and historians such as Bill that Fall River’s rich, but fading, legacy is kept alive.

As we slowly walked along the remains of New Boston Road, we passed the location where the Arabian horse stables once stood. Nothing but a tall grove of trees now exists. On the south shore of the island, just beyond the ice house, one must strain the imagination to picture what once stood here. It must have been a majestic sight of Borden’s regal stallions romping along open fields flanking the gentle lapping shores of the pond.

Soon we came upon the toppled ruins of a shallow foundation. A tall thin tree sprouted out of the center of the living room. This was once the location of the Benjamin Cunningham house. It was one of the oldest structures on the island and still exists to this day. This discovery was of great pleasure to me since I knew where the Cunningham house had been moved to. A somewhat large Colonial Cape, with Greek revival variation, it now stands at 132 Bark Street in Fall River, not far from Lafayette Park. Its present owner demonstrates his pride for his building in the dignified way in which it is maintained. For the most part, the place has been kept intact both inside and out, with very little in the way of modification over the years. With its tastefully painted gray clapboard siding, ornate white trim, and commanding, but inviting front door, the old place stands noble and proud as it once did in another time and place.

We continued our walk deep onto the island. Trees above now scaled the road from side to side. The fresh spring greenery shaded our heads like an olive pastel parasol. Demonstrating an elusive danger, John brushed his hand along the lush bushes by the edge of the road, coming up with a deer tick. His lesson to us was one of vigilance—to keep a close look out for ticks that infest the island. An avid hunter, John is accustomed to dealing with these minuscule pests. Gone undetected, a diseased tick can imbed itself under the skin and transfer the crippling and life debilitating Lyme disease. With escalating reports of the disease every year here in New England, these tiny pinhead sized menaces cannot be ignored. If bitten by one of these primitive, tiny crab-like creatures, it is best to get to a hospital. At the end of the day, like grooming monkeys, we picked several of these blood-sucking creatures from our socks and clothing.

The Location of the Big House

We ran into a minor roadblock as New Boston Road ended and the route took a turn to the left. The pond had covered the road ahead of us. Just to the right was the old location for the North Watuppa boat ramp, long gone. This flooding left us no choice but to scale a fieldstone wall to avoid the encroaching water. A short trek through the woods and past another stone wall and we were soon on Acacia Avenue. Not on city maps, Acacia Avenue was a private road, probably named by the Borden family. It led directly to what was lovingly referred to by the family as the “Big House.”

Not far from the “Big House,” Spencer Borden, Jr., Borden’s oldest son, had built his own dwelling, along the southeast shore of the Watuppa. While the older sibling went on to share in his father’s successes, the Borden’s youngest son, Brooks Borden, a star high school football player, was not so fortunate. Brooks had taken part in a country sleigh ride with a group of fellow students from Durfee High School. As the sleigh carriage crossed the railway tracks at Brownell Street towards Main, a south bound Boston train slammed into it. Tragically, Brooks and two other boys were killed.

Acacia Avenue, now grass-covered and leaf-paved, took us ever nearer to the end of the island and the location of Spencer’s “Big House.” At still another divide in the road, Bill opened his notebook and began pointing out the locations of significant landmarks long transformed and concealed by dense overgrowth. At what appeared to be a split in the road, another small lane set off to the left. Covered by thick shrubbery and vines, an abandoned stone wall disappeared into the woods beside it. Bill explained what we were looking at. “If you followed this wall in Borden’s day it led down in this direction to finely cultivated gardens and to an arched tower with a bell that Borden had purchased out west, from California. Borden acquired the bell from the ruins of a mission church.”

Stefani and I hovered over Bill’s shoulder, studying the photographs he revealed, as John walked off to explore the small lane. Displayed in Bill’s notebook were images of meticulously cultivated gardens and sweeping open fields of grazing land. In the center of one of the photos was a tall church-like double arched stone structure with a bell near its peak. The bell, which was chronicled as coming from the ruins of the Mission La Purisima Concepcion on the west coast, was made to sound on the hour. Spencer, a good friend and associate of Thomas Edison, had set up an electrical clock synchronized to sound the bronze bell. Bill pointed beyond a stretch of young trees and continued his visual tour. “This road to the left here led to a causeway built by Spencer Borden for easier access on and off the island.” The road he pointed out was no more than a footpath now. “Just when the city was trying to control all the water along the shore of the North Watuppa, Borden builds this causeway to Meridian Street which angered the city.” Bill points in another direction. “If you follow this little road out, it would take you to the causeway—but it has been under water for some time now.”

Just as Bill announced that we were almost at the ruins of the house, the battery on Stefani’s video recorder expired. That was unfortunate. To me, this portion of the walk was the highlight of the tour. As we approached the remnants of the Borden house, I expected to find nothing left. To my excitement and pleasure, the entire foundation to the old homestead was very much intact. The cellar walls were constructed of fieldstone. Fall River was known for its quarries where granite was king, but Borden was not your common industrialist homebuilder—he had used existing fieldstone from his fields, rather than granite that was used almost exclusively throughout the city, to build his foundation. Borden was very much rooted in the land, and decided to use what was easily available, intrinsic, and customary to an English country manor, if not his pocketbook.

The sight of the ruins was a poignant moment for me. Several large trees grew out of what was once the cellar floor. Three granite steps at the center of the foundation placed us on the front terrace, or what was left of the paved floor of a once majestic veranda. Where the front door once stood was now the edge to the stone foundation and a four foot drop. To the left and right of the imaginary front door, the crescent shaped foundation sat still intact. These two bites once supported grandiose turret windows.

Looking across to the back wall we saw another group of stairs, once the rear entrance to the house, which was blessed with a magnificent view overlooking the unspoiled north end of the pond. Over to the right side of the front terrace lay an old jade green tile floor, crumbling over its cement bed. I looked down at it in metered sadness as everyone pondered whether the shattered and once glazed floor was part of the exterior side veranda, or perhaps an interior sunroom. This end of the house was partially exposed to the early eastern sunrise. A finely carved hardwood railing once enclosed the terrace overlooking this end of the house. Tightly placed white carved balusters were surrounded by stout brick pilasters, crowned by meticulously trimmed tall fir shrubbery. It was all so grand.

Bill beckoned us to follow as he walked down to the shore of the pond. Here we discovered a fieldstone chimney about sixteen feet tall. With the high pond levels, it now stood in about two feet of water, its hearth and grille protruding just off shore. High and dry up the beach was another structure, deep foundation to a once small building. Bill, always the consummate teacher, quizzed us as to what we thought it was. The resounding conclusion labeled it as some sort of bathing house. Along the shore, beneath the wavy shadows of the crystal water, lay a golden sandy bottom. I remembered the South Watuppa having a couple of native sandy beaches such as this, but one can only guess whether this was a natural setting or if Borden had the sand shipped in. This was a wonderfully remote and private area. Here the Borden family must have spent many a summer day and evening dining, swimming, and just lounging along a tranquil shore, especially since the pond was only a couple of hundred feet from the house. One can easily picture old Spence standing by the pond sporting a pot belly and straw hat tying up loose ends to a new business venture, signing a multi-million dollar contract, or making a smooth business deal with a pen in one hand and a glass of sherry in the other. What a picturesque and tranquil setting it must have been—and in many ways, still is.

Our Expedition Continues

After snapping a few more photographs, the tour concluded and we started back towards civilization. Bill occupied the remainder of our walk with stories about the Borden family. We were shown the approximate location of Spencer Borden, Jr.’s home, but thick brush prevented us from locating where it once stood.

Col. Spencer Borden died at the age of 72 in 1921 while at leisure in Vermont. His wife of fifty years, Effie, died less than five years later. Their son, Spencer Borden, Jr., died at the seasoned age of 85 in 1957, outliving his wife Sarah by 26 years. Spencer Jr.’s grave lies at the family plot at Oak Grove Cemetery just behind Spencer senior and near Spencer Borden III, whose grave reads: born September 6, 1903, died February 2, 1909.

Not long after Col. Spencer Borden’s death, Interlachen, and the “Big House” was sold. Sometime later, in the late 1930s, the city was given the opportunity it always desired. Finally, it had snatched the shiny brass ring—sole possession of Interlachen. But the prize would not shimmer for very much longer. In all their wisdom and with blind prudence, Fall River had Interlachen, the “Big House,” demolished. Merchants and hawkers stripped the impressive three-story mansion of its entire oak paneling, windows, and anything else of value it could ravish. By the 1940s, the entire island became the possession of the Fall River Water Department. And finally, RT 24 was constructed, becoming a natural barrier from intruders between New Boston Road and the island. Like a lost forgotten land, Interlachen has stood undisturbed for over 65 years. Though its countless potentials are inviting, it is probably best left alone as open undeveloped space and used for rustic historical nature walks such as the ones given by Bill Goncalo.

In 2004, while teaching at Bishop Connelly High School in Fall River, Bill Goncalo involved his students in an historic journey of discovery and explorations of Interlachen called “Forbidden Places and Forgotten Spaces: Exploring Interlachen’s Watershed Areas.” The course taught sophomore students the important values of our common past and the merit behind civic pride and responsibility. Emphasis was placed on communication skills and the passing on of knowledge and awareness to others in the community—just as his father passed these vital virtues on to Bill when he was a child. Later in the curriculum, students had the opportunity to exercise their newly acquired skills and lead a weekend tour of over 200 residents. The young tutors even created their own Interlachen Tour Brochure, with photos and descriptions of how life once was on the island.

One student who expressed her excitement about the class concluded by adding: “I now see Interlachen as Fall River’s Walden—my Walden.” Stefani, John, and I walked away from the tour with similar sentiments. Not only can Interlachen be compared to Thoreau’s tranquil Eden, but with the awareness Bill brings for this scenic and forgotten historical corner of Fall River, I can truly affirm that Interlachen is Bill Goncalo’s Walden Pond.