by Mary Elizabeth Naugle

First published in June/July, 2005, Volume 2, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

The eye of the modern reader is likely to skate over the clothing references in the Borden case, while a chorus of nagging questions chant in the background: just what is meant by a wrapper, a cardigan, congress shoes, Oxford ties, Bedford Cord, or Bengaline Silk? The men in the case were thoroughly baffled then; both sexes are baffled today. Fortunately, catalog reprints and Internet access can shed some light on the subject.

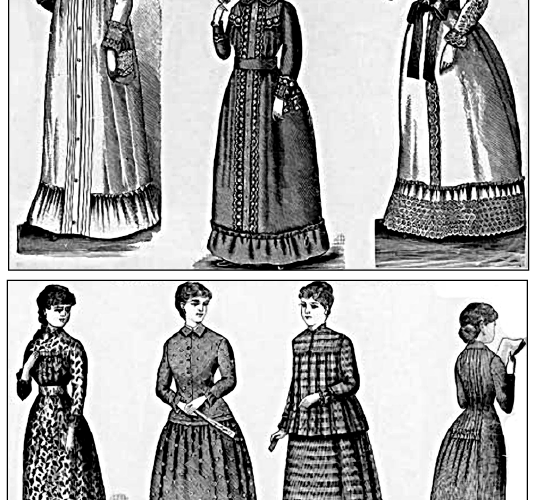

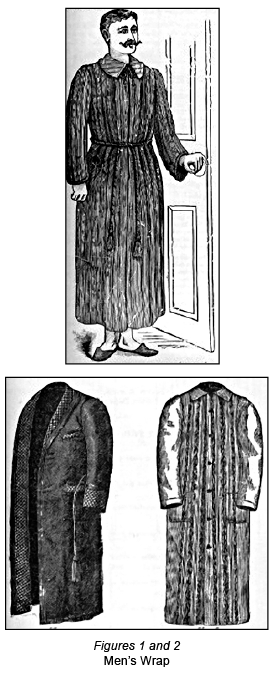

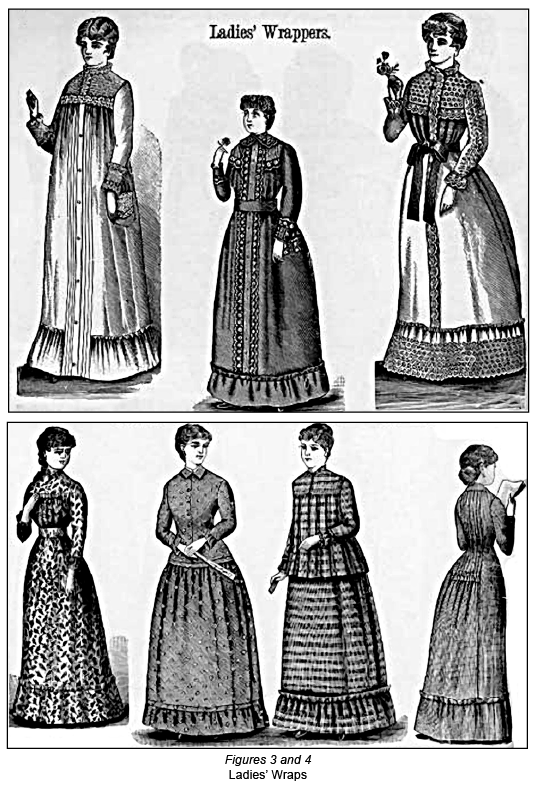

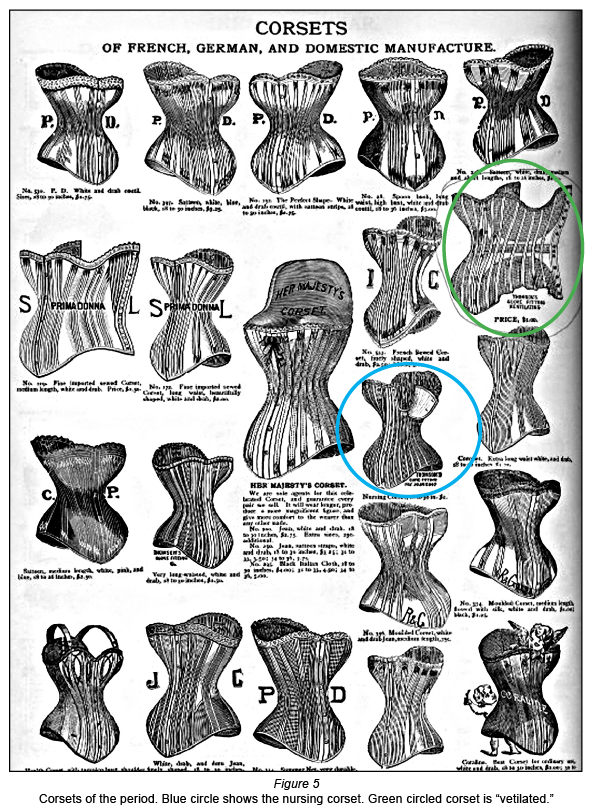

First, the question of the wrapper. Men at the time were likely to confuse the term with what they themselves referred to as a wrap (Figures 1 and 2) and what we would call a bathrobe today. Hence the line of questioning that pursued the possibility of Lizzie having concealed a bloodstained dress beneath the pink striped wrapper in which she reluctantly received police the day of the crime. A bathrobe could indeed conceal one, even two dresses, but a wrapper would bulge absurdly if thrown over a Bedford Cord. Why? Because the garment was not a robe, but a day dress—something worn for comfort and ease—that would be perfectly presentable to answer the door in, but not to be worn past the threshold. It in no way resembled a nightgown or robe. It was very like a dress except in weight, which in summer would be lighter, and fit, which would be somewhat freer to allow a slight loosening of the corset for housework or leisure. Robes (for warmth or additional modesty) were available to go over the wrappers, but are never pictured in the catalogs. The wrapper, like the dresses of the time, was still form fitting (Figures 3 and 4), except when intended for expectant mothers, who were permitted for the first time since childhood to go corsetless. Confinement would be literal for these women given over to maternity wrappers until childbirth allowed them to return to the light of day in corsets thoughtfully designed for nursing (Figure 5).

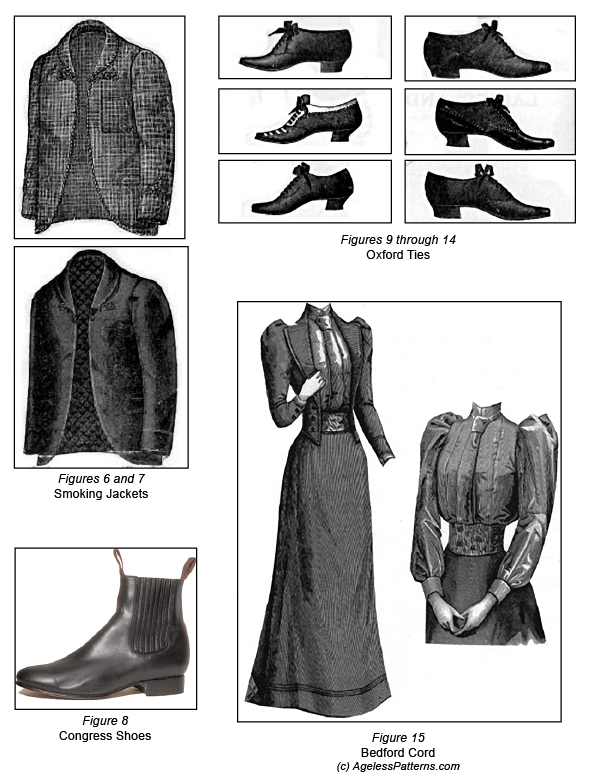

As for the cardigan, it is probably a man’s equivalent to a wrapper. Andrew is said to have been wearing one, yet the photo reveals nothing like the sweaters of today. Instead, we see something more like a suit jacket. The term cardigan is not used by the catalogs, but they do show smoking or house jackets (Figures 6 and 7) that are probably similar to Andrew’s cardigan. Like the wrapper, the cardigan was of looser fit and comfier fabric—especially when compared to a Prince Albert coat. Just the thing for a late morning nap.

A pair of congress shoes like the ones in which Andrew’s feet were still firmly planted may be seen in Figure 8. The elastic sides, or gaiters, were what made them congress. Even unregistered voters could wear them. A pair of Oxford ties like Lizzie’s are pictured in Figures 9-14. They are merely sensible tied shoes, and Lizzie could wear them even though she lacked a high school diploma.

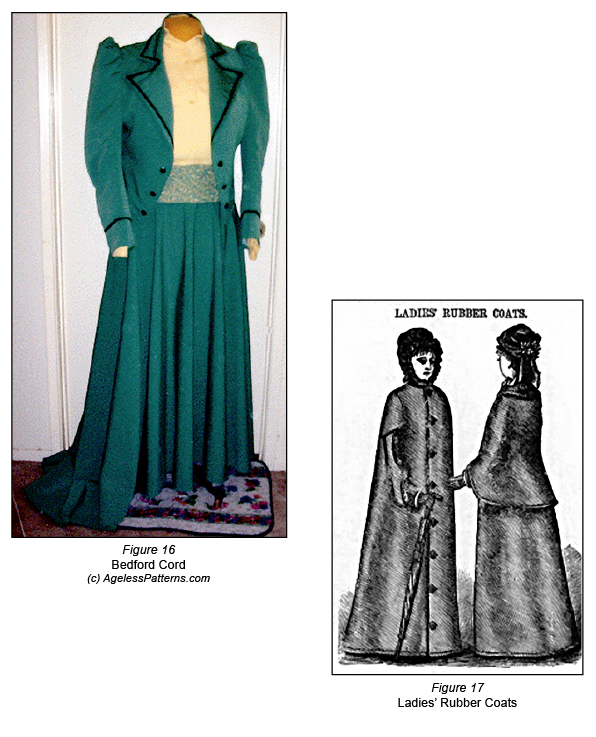

The final two questions concern fabrics and are pivotal to the case. First, let’s address the Bedford Cord. The dress that Lizzie burned was of this fabric. It was a cotton with a ribbed or corded weave. Interestingly, it was relatively new, having been introduced the year before in the Jordan Marsh catalog of Boston. As Victoria Lincoln pointed out, Bengaline Silk was likewise ribbed. The on-line resource Textile Links describes it as a silk that “often has wool or cotton in ribs.” The fabric when cut into ribbon width is known as gros-grain. So the corded aspect of the two fabrics was the same, but the Bengaline had a faint sheen from the silk content. Lincoln stretches her point, however, when she addresses the unsuitability of the fabric when compared to a shirtwaist cotton dress. She claims the fabric is too heavy for summer, too dressy for daywear, and ill-suited for lounging “about the house through a record-breaking scorcher of a day.” However, Figures 15 and 16 show a skirt and shirtwaist (a blouse) of Bengaline that is clearly intended for warm weather. This costume follows an 1892 pattern that calls for contrasting fabrics for skirt and waist. That is not to say that Lizzie did wear the Bengaline that morning, but that she could have without the choice being an unusual one.

The clothing turned over to police included the blue shirtwaist, blue Bengaline skirt, (washed) black stockings, Oxford ties, and an underskirt. Apparently, neither Lizzie nor the constabulary of Fall River thought it necessary to pursue the matter further. However, her wardrobe would also have included a corset (preferably a breezy ventilated number as in Figure 5), a corset cover or chemise, and drawers. Rather than commit the crimes in brazen nakedness, she may have elected to commit the crimes in these, then burned the evidence in the stove.

Yet, for the ultimate in modesty and protection, Lizzie may have draped herself in a floor length rubber gossamer, as suggested by those writing to Hosea Knowlton with their theories of the case. It could be quickly sponged off, and if it was like the garment pictured in Figure 17, it could have been, after all, reversible.

Special thanks to AgelessPatterns.com for graciously allowing us to use Figures 15 and 16 in this article.

Works Cited:

Bloomingdale Brothers. Bloomingdale’s Illustrated 1886 Catalog. NY: Dover Publications, 1988.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts VS. Lizzie A. Borden; The Knowlton Papers, 1892-1893. Eds. Michael Martins and Dennis A. Binette. Fall River, MA: Fall River Historical Society, 1994.

“Dresses 4.” Ageless Patterns.com 3 May 2005. < http://www.agelesspatterns.com/dresses_4.htm> (20 May 2005).

Jordan, Marsh and Company. Jordan, Marsh Illustrated Catalog of 1891. NY: Dover Publications, 1991.

Lincoln, Victoria. A Private Disgrace: Lizzie Borden by Daylight. NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1967.

“Terms & Definitions.” Textilelinks.com 1999. < http://www.textilelinks.com/author/rb/blterms.html> (20 May 2005).