by Eugene Hosey

First published in August/September, 2005, Volume 2, Issue 4, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

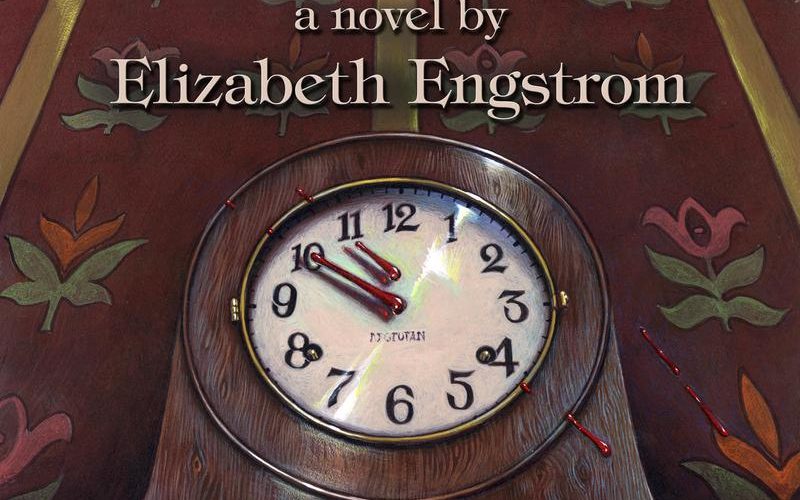

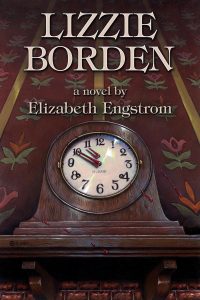

The ideal fictionalization would not cheat on a scholarly consensus of what constituted fact. At the same time, it would deliver something new that filled in the gaps of information and connected the dead-end trails of evidence. The essence of the solution to the mystery might include almost anything – so long as it worked within rational parameters. If such a book does not exist, it is not because there are no creative writers among the Bordenphiles. It is because it’s a damned difficult assignment. But I was reassured that it was a worthy goal after reading the Engstrom book, which is everything a fiction about Lizzie Borden should not be.

The ideal fictionalization would not cheat on a scholarly consensus of what constituted fact. At the same time, it would deliver something new that filled in the gaps of information and connected the dead-end trails of evidence. The essence of the solution to the mystery might include almost anything – so long as it worked within rational parameters. If such a book does not exist, it is not because there are no creative writers among the Bordenphiles. It is because it’s a damned difficult assignment. But I was reassured that it was a worthy goal after reading the Engstrom book, which is everything a fiction about Lizzie Borden should not be.

In all fairness to the writer, this book is no worse than a lot of published fiction; and she does not claim to have solved the actual mystery. Also, when the book was printed in 1991, the transcripts and other source material were not as readily available. On the other hand, perhaps it is not wise to attach a real historical figure to a work of self-indulgent fiction. When there is quite a bit of serious research on the subject, a naive effort will seem foolish. Lizzie Borden is so titled as to be automatically added to the Borden literature, where it is really a curious failure. By default, any book bearing the name of Lizzie Borden is subject to criticisms from the case scholars. Clearly, Ms. Engstrom is not aware of such people, nor is she seriously interested in solving the case or understanding the principals.

I cannot help but think the whole narrative could have been stronger had she never used the Borden name. In that case, the author may have felt free enough to develop the story into one worth telling. As it stands, it is hard not to laugh at just about everything Engstrom delves into– not only at the “solution,” but at the characterizations and even some of the writing itself. The story is a lurid soap opera with unconvincing characters that childishly whine about their pointless lives until axe murders render meaning. But by then, the story has ended.

Bridget is not even a maid. She is strictly a window-washer. Andrew grumbles that is all she does – wash windows – and he can’t bear it any longer. Emma doesn’t think she washes windows enough and assigns her the whole ground floor of windows for a day, which Bridget thinks is unreasonable. (Engstrom may have stumbled onto some truth here.) And, of course, nobody can get Bridget’s name right.

Abby cannot bear Emma, but she wants Lizzie to like her. Abby fantasizes about playing with Baby Lizzie again. Abby’s fat body and ravenous appetite comprise at least 90% of her character.

Emma hates life at home and is hell for all to live with. Periodically, she checks into a room in New Bedford and orders a liquor supply. She always comes home sick and bruised.

Andrew is trapped in a self-made prison, fearing loss but hating what he has. He misses his younger years, when the girls were children. He has an affair with the widow Crawford, a prostitute, who also has an affair with Lizzie.

The tragedy is foreshadowed by a Prologue in which Lizzie and Andrew go fishing. Lizzie catches a fish and Andrew murders it with a rock. But the modus operandi of the August 4th murders has its genesis in Lizzie’s trip to Europe. While crossing the English Channel, Lizzie meets a distinguished lady named Beatrice who, in corresponding with her afterwards, sends her a book of meditations or spells, called Pathways. This is supposedly a “program of growth” and requires a private place like the barn. Beatrice also renames Lizzie – that would be, Lizbeth.

To Engstrom’s credit, the Pathways phenomenon answers three big questions about Lizzie’s part in the murder mystery: During the crimes, where was Lizzie and why? And why did Lizzie burn a dress? A supernatural solution is intriguing, but Engstrom fails to develop a potentially spooky situation. When Lizzie does her meditation in the barn, a Lizzie double that the “real” Lizzie cannot control materializes somewhere and does something. For example, a naughty Lizzie struts downtown and messes with a pharmacist’s head about buying prussic acid just for the fun of it.

I hate to call a book trash. But when the author works this frivolous narrative to a truly sick conclusion, after putting a note up front that her intention is not to offend, but to “justify,” I feel sick myself in contemplating the rationalizations of a mind that so easily, so utterly, ignores the moral implications of two brutal murders. While killing Abby, Lizzie is masturbating. When killing Andrew, Lizzie is eating a pear. So maybe Lizzie is responsible for her double, maybe she isn’t. What about the weapon? Does it appear and disappear with the doppelganger? This would explain why it could not be found. But it doesn’t matter anyway. Understanding what inspired the author about Lizzie Borden would be the real story.