by Eugene Hosey

First published in October/November, 2004, Volume 1, Issue 5, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

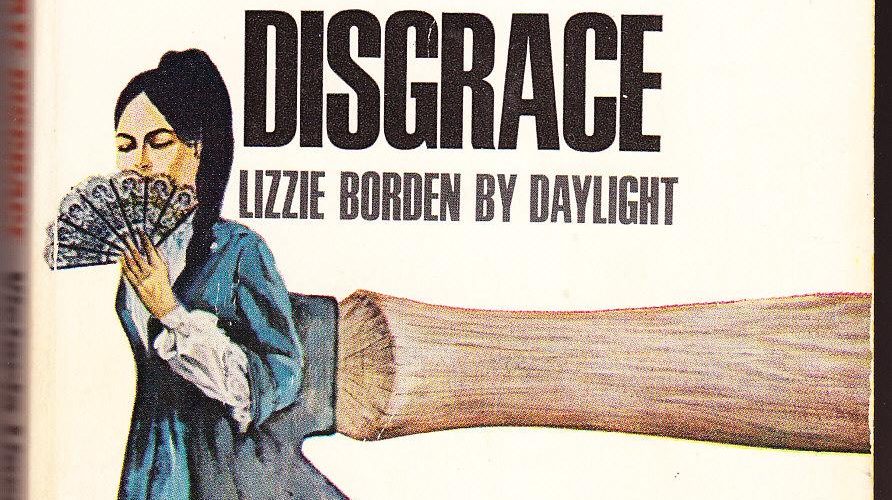

A Private Disgrace: Lizzie Borden by Daylight is probably the best story yet written about the legendary New England spinster who took an axe to her parents—and through some bizarre combination of cunning and luck—got away with it. Its effectiveness is something of a phenomenon among the Borden books. The narrative is so eerily detailed and at times vivid that the Lizzie scholar finds “Lincolnisms” to unlearn long after he or she is satisfied that the book is a work of imagination. This is a testament to Victoria Lincoln’s talent as a novelist. For the objective crime-solver, she is a peculiar case. As compelling as her reasoning often seems to be, it is just as often difficult to resolve it with actual evidence.

Ms. Lincoln is quick to let us know that she is not just another disadvantaged story-teller, speculating about the crime from afar. The case is part-and-parcel with her own heritage – her voice in it more or less a birthright. According to Victoria Lincoln, a native of Fall River, the legend is true. But the hows and wherefores of the mystery would forever remain shrouded if not for the fortuitous revelations of “insider” knowledge. As a child, the author lived within two blocks of Maplecroft and remembers seeing Lizzie almost every day. She observed the actual living, breathing incarnation of the sphinx of parricide herself – the Fall River pariah with the startlingly pale blue eyes, who filled bird feeders and habitually rode in her black funereal limousine. Lincoln recalls what seemed to her an odd remoteness in Lizzie’s disposition when she tried to talk to her. These childhood memories or impressions are gems to Borden enthusiasts. We cannot help but appreciate the author for sharing them with us.

In fact, Lincoln writes an unusually vivid word image of those “peculiar” Lizzie Borden eyes – a feature often mentioned since the days of the trial as cryptic—but inadequately described. Lincoln verges on the poetic in attempting to do them justice: “And photographs assure me that her eyes, too, were as I remember them, though in some pictures they show as darker than they really were, because their pupils were so distended. The eyes themselves were huge and protruding, the irises an almost colorless ice-blue. They were strangely expressionless. I have heard many speak of them as dead eyes, but the eyes of the dead are dull; Lizzie’s had the shine of beach pebbles newly bared by the outgoing tide.” But this sort of treat is the bright side of a two-sided coin – the dark side of which becomes apparent when she feels too keenly a sense of her own celebrity as a factor in the legends. She can’t resist dispelling rumors that she accepted cookies from Lizzie or that her grandfather was in the carriage that stopped at the Borden house murder morning. This voice becomes a pretentious tactic in her effort to convince us that she knows what she is talking about. She might as well say, “As a member of the same social clan to which Lizzie Borden belonged – an almost inexplicable inner circle of special insight up on the hill – you can take my word for it.” Statements such as this one, meant to impress, cannot truly convince: “We had no doubt that she did it. We also had no doubt that though Lizzie loved money fully as much as old Andrew ever did, she had loved him even more. We wasted little time wondering how anyone, even Lizzie, could nurse for five years a smoldering, mounting, murderous hate for anyone as dismally uninteresting as Abby Borden, and plot for two weeks her death by Prussic acid. We did, however, attach grave importance to Lizzie’s ‘peculiar spells.’ ”

Unlike many of the authors, Victoria Lincoln does not shy away from explaining the grisly details of one of the most disturbing, vexing murder cases in American history. Lincoln exudes an infectious confidence and excitement as she shines her own daylight on Lizzie Borden. She fits together piece after piece of the puzzle with a clever talent for invention. Clearly, she means to deliver the goods. We want to know how Lizzie got away with it. And she really does understand the mythic proportions of her subject matter, as evinced by this insightful passage: “The case has always held its honest students spellbound, because the factual evidence of her sole opportunity and her guilt is so overwhelming, yet the bare idea of her guilt is so humanly incredible, so absurd. Ever since she was acquitted, Lizzie the legend, Lizzie the case, has fascinated writers; she has to be made plausible.”

Victoria Lincoln’s Lizzie Borden suffered from a form of epilepsy of the temporal lobe. An attack resembled sleepwalking, or a brownout, somehow connected to her menstrual cycle, during which time Lizzie was capable of irrational behavior or fits of violence. (Known by the inner circle on the hill as Lizzie’s “peculiar spells,” Ms. Lincoln lets this cat out of the bag for the first time.) During one of these spells, Lizzie murdered Abby over a property transfer. This first murder was an orgasm of hatred. Then Lizzie hid the axe in her bedroom slop pail, cleaned herself, and changed for the street with the intention of establishing an alibi. But because Andrew got home before she could get out of the house, she had to alter this plan and murder her father as well, in order to get away with it.

Lincoln feels certain of her intuition when explaining such details as the pinpoint of blood on Lizzie’s petticoat, Lizzie’s own mention of a chip of something she picked up, the pulled-loose condition of Lizzie’s blouse as noticed by Alice Russell. The author’s stated working sources were the Trial transcript and the coverage from two newspapers, The New York Times and the Baltimore Sun. Lincoln’s most original contributions to the case are about Lizzie’s dress of murder morning. Indeed, it is a much bigger issue than a mere dress. If Lizzie’s own hands swung an axe, shouldn’t there have been a bloody dress somewhere at some point? If so, where could it have been hidden? And how many dresses were involved anyway – one, two, three? What was Lizzie wearing when she stood behind the screened door and invited Mrs. Churchill to the crime scene? There was the dark blue bengaline silk with the light or white pattern on view in the courtroom. There was much talk about a cheap cotton Bedford cord made for Lizzie that spring of 1892. No blood was found on any of Lizzie’s dresses, and none observed on her at any time. And there was Alice Russell’s confession about the Bedford cord in the kitchen cupboard in connection to Lizzie burning something in the stove. There is something endlessly fascinating about Lizzie’s attire. Perhaps it is the image of the feminine Victorian dress, bloodied by a monstrous act, that conjures up feelings too creepy to ever quite shake. Apart from the weapon (successfully cleansed or missing), the circumstances surrounding Lizzie Borden’s dress of August 4th, 1892, are possibly the most controversial and divisive of the Borden case debates.

The Victoria Lincoln theory of how Lizzie concealed, destroyed, and made substitution for a damning bloody dress is not just interesting, but revealing. In basing her case on a subjective application of evidence, she inadvertently calls attention to the need for a definition of what constitutes objective analysis. Lincoln’s concealment theory (one that has attained a mythical status, in fact) is that Lizzie hid her bloody Bedford cord on a hanger underneath another dress. She does indeed use actual testimony (misquoted in fact) from George Seaver:

A. Captain Fleet was with me, and I commenced on the hooks and took each dress, with the exception of two or three in the corner and passed them to Fleet, he being near the window; he examined them himself, he more carefully than myself. And I took each garment and hung it back, all excepting two or three which were heavy or silk dresses in the corner. (They are looking, you see, for a cotton.) Those were silk dresses, I am very sure, heavy dresses, and they stood there and I did not disturb them at all. I didn’t see any light-blue dress with diamond-shaped spots and paint around the bottom of it or the side.

Thus, the rationale for Lincoln’s concealment theory – a smart idea, a possibility that cannot be proven or disproven. Akin to the illustration of the unheard tree falling in the forest – did it make a sound?

To complete the solution to the dress mystery, Lincoln has Lizzie wearing a dark blue bengaline silk dress when she was observed by witnesses before she went up and changed into the pink-and-white stripe garment – the same blue bengaline she gave the police as her murder morning attire. In other words, Lizzie was at least half-honest about this. After murdering Abby, Lincoln’s Lizzie Borden dressed in the “dressier” silk-type dress appropriate for the street. After Andrew’s unfortunate return, Lizzie noticed his Prince Albert on the coat rack and suddenly had a clever idea to use it as a blood-spatter shield. This time, Lizzie broke the axe handle in a vise in the barn, burned the handle in the stove, and successfully cleansed the blade which she then tried to inconspicuously place in a box in the cellar.

How plausible are Lizzie’s murderous actions when examined from this point backwards? Had Lizzie been a few minutes quicker in leaving the house, for example, was she going to leave the murder weapon in her slop pail for the police to find when Abby was discovered? If nevertheless true, Lizzie was undoubtedly wiser the second time around to do something about the weapon; and thinking along the same lines, she might have saved us all a lot of trouble by burning the dress along with the axe handle. Without witnesses to the actual murders, the killer’s movements are fairly open to speculation.

However, there are eyewitnesses to the singular but important question of what Lizzie was wearing murder morning. Much speculation stems from the fact that neither Alice Russell nor Bridget Sullivan could recall anything about it. Naturally we wonder why and it is tempting to theorize. But how can such memory lapses really be explained? More to the point, how much weight should be given these lapses among witnesses – witnesses who provide us nothing toward answering the question – when there is one witness who does remember and frankly tells us?

Mrs. Churchill testified at the Inquest, the Preliminary, and the Trial. She distinctly remembered a cotton dress of a light blue and white groundwork with a dark blue diamond print. At the trial, Mrs. Churchill was shown the dark blue dress Lizzie claimed to have worn murder morning:

Q. Was that the dress she had on this morning?

(Showing dark-blue dress.)

A. It does not look like it.

Q. Was it?

A. That is not the dress I have described.

Q. Was it, the dress she had on?

A. I did not see her with it on that morning.

Q. Didn’t see her with this dress on that morning?

A. No, sir [T 352].

On cross-examination, by Robinson:

Q. And there was a white thread and a blue thread mixed?

A. Well, I am not positive. I only looked at the general effect. It looked like blue and white groundwork to me, with this deep navy blue diamond printed on it.

Q. Was the groundwork in any stripes?

A. I don’t know: I don’t remember about that: I remember the diamond upon it.

Q. Can’t you help us a little bit about that, because we are trying to get at it?

A. Well, the diamond is the most distinct thing in my mind. It had a navy blue – well, my dress is navy blue – similar to that.

Q. That was the figure?

A. The figure that was printed all over the goods.

Q. Was it a calico dress – a print, as it is sometimes called?

A. A cotton dress, either calico or cambric. It was cotton: it was either calico or cambric, I think.

Q. I suppose you had not the least occasion to examine that dress that morning?

A. No, sir: only I had seen it before [T 361].

[. . . ]

Q. Well, was it a tight waist or a loose waist?

A. It was not tight [T 362].

[. . . ]

Q. What do you ladies call it? Do you have some name for it?

A. I don’t know exactly, but it seems to me there was a box pleat or something down the front, like a blouse waist or something, loose, like that [T 362].

Mrs. Churchill apparently was not familiar with Bedford cord, which is basically a type of weave producing a corded effect. Her effort to describe “a box pleat or something down the front” is a reference to the style of a loose-fitting blouse but – at any rate – Mrs. Churchill’s description is a very close fit to the dress Alice Russell saw Lizzie take from the kitchen cupboard with the apparent intention to burn. Miss Russell remembered it as a Bedford cord dress that Lizzie had made for her the spring before the murders; she did not recall seeing it again until seeing a portion of it in the cupboard.

Though neither witnessed what Lizzie wore on the tragic morning, both Emma and Mrs. Raymond, the dressmaker, remembered the Bedford cord. Mrs. Raymond from the Trial:

Q. Can you describe the dress?

A. It was a light blue with a dark figure [T 1578].

[. . . ]

Q. Now what was the material of which this Bedford cord was made?

A. Why it was a Bedford cord. That was the name of the material.

Q. Well, I meant as to whether it was cotton or woolen or cheap goods?

A. It was cotton, a cheap cotton dress [T 1578-79].

Emma Borden from the Trial:

Q. What sort of figure was it in that dress?

A. You mean shape?

Q. Yes.

A. Or color?

Q. Shape.

A. Well, I don’t know how to describe it to you. It was about an inch long by about three-quarters of an inch wide.

Q. Can’t you give me any better shape of it than that?

A. It was pointed at the top and broader at the bottom than it was at the top.

Q. Sort of triangular?

A. Well, perhaps so.

Q. And that was a dark-blue figure?

A. I think one part of it was black or very dark blue and the other part a very light blue.

Q. That was a Bedford cord?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. It was a cotton dress?

A. Yes, sir [T 1573].

It is hard not to notice the similarity between Emma’s triangular description and Mrs. Churchill’s “diamond.”

Ms. Lincoln states that “no two witnesses agreed on what Lizzie wore.” It is a misleading statement that serves as a kind of cover for the author’s lack of diligence concerning these testimonies. The more appropriate question is whether a consensus of any kind can be found.

Dr. Bowen and Officer Doherty have little to offer about Lizzie’s dress, but what they are able to say is not inconsistent with Mrs. Churchill’s memory of what she saw Lizzie wearing in comparison to what was produced in court. Having earlier described it as “drab” and as “a sort of morning calico dress,” Bowen is shown the dress that had been given to the court:

Q. What color do you call that dress?

A. I should call it dark blue [T 314].

Officer Doherty from the Trial:

Q. Now if you please, return to the time you saw Miss Borden in the kitchen. Can you give any description, and if so do it the best you can, – of the dress that she had on when she was down stairs in the kitchen?

A. I thought she had a light blue dress with a bosom in the waist, or something like a bosom. I have a faint recollection; that is all I can say about it. I thought she had a light blue dress with a bosom in the waist or something like a bosom, and that is about all the description I can give [T 599].

[. . . ]

Q. Any figure, – do you remember any figure?

A. I thought there was a small figure on the dress, a little spot like [T 599].

[. . . ]

Q. Well, if that is the best you can do, I will ask you if it was that dress? (Showing witness a dress)

A. No, I don’t think so [T 599].

Doherty’s “bosom in the waist” is awkward, but it makes more sense if he is trying to describe a loose-fitting blouse.

The dress that was exhibited in court is unfortunately rather sparsely described, though sufficiently enough to distinguish it from the Bedford cord or something like the Bedford cord. This is Lizzie’s description of what she wore: “I had on a navy blue, sort of a bengaline or India silk skirt, with a navy blue blouse.” The color and pattern of the dress exhibit is recorded in the Trial during the testimony of Marianna Holmes in the court’s parenthetical note: “(Showing dark blue dress with small light figure).” When Miss Russell was shown the skirt she said, “Well, I don’t know what it is. It is silk, but I don’t know what kind.”

The author believes that Lizzie successfully confused the witnesses by having the foresight to change into a similarly colored dress after killing Abby – specifically, a dark blue dress with a light pattern; in essence, an inversion of the light blue dress with the dark figure remembered by Mrs. Churchill. But who did Lizzie fool? Apparently, no one – except, at first glance – Phoebe Bowen. Mrs. Bowen, from the Trial:

Q. What kind of a dress?

A. A dark dress.

Q. Can you describe the dress any more fully than that – a dark dress?

A. It had a blouse waist, with a white design on it.

Q. Had you ever seen the dress before?

A. I noticed nothing unusual about her dress.

Q. Whether or not that looks anything [like] the waist she had on that morning? (Showing waist)

A. I should say it was [T 1585-86].

But after being reminded (erroneously) under cross-examination that she had described Lizzie’s dress in the Preliminary hearing as “A white dress with a waist with blue material, a white spray running right through it,” she is asked to again verify whether this dress exhibited was what Lizzie wore. (Actually, Mrs. Bowen is quoted in the Preliminary Hearing as saying “A blouse waist of blue material, with a white spray, I should say, running through it.”) Phoebe Bowen’s first description of Lizzie’s dress was consistent with what Mrs. Churchill never doubted.

Q. That would not be described by you as a blouse waist of blue material with a white spray running through it?

A. That would not.

[. . . ]

Q. Were you an intimate friend of the family, Mrs. Bowen?

A. Yes, sir.

[. . . ]

Q. Is your recollection of it any better now than when you gave that answer?

A. No, sir [T 1589].

This is the extent to which Victoria Lincoln could have referred to actual testimony to make her case for Lizzie changing out of a bloody Bedford cord cotton into a dark blue bengaline silk – the at least confused, if not dishonest, testimony of a friend who would prefer to remember in Lizzie’s favor. What is especially bewildering about Lincoln’s convoluted reasoning is that she herself does not believe Phoebe Bowen’s effort to remember this dark blue bengaline as The Dress. The author practically confesses to having ignored testimony in producing her theory: “It is amusing that the one person who claimed to remember the dress that Lizzie, in all probability, actually wore under the eyes of all those witnesses, believed herself to be lying.” And it is striking how the author found ways to work around the eye-witnesses, as opposed to through them.

It is Mrs. Churchill who gives us the accurate description of what Lizzie wore; whether or not it was what Miss Russell saw in the cupboard, it was not the dark silk-type dress with the light figure on display in the courtroom. When a witness says, “I don’t remember,” there may understandably follow in the investigator’s mind an implication that seems highly probable – one which then leads to further deduction. But it remains true that a credible memory offered in eye-witness testimony is fundamentally different from an “I don’t remember” testimony. A verbal observation does exist. A witness who does not answer a question gives us nothing more than another question, another possibility. The failure to make this distinction in the first place is the basis upon which Ms. Lincoln subjectively weaves her tale about Lizzie’s dress.

Ultimately, Victoria Lincoln’s dress-switching story of murder morning succeeds only by depending upon a man’s poor knowledge of dress goods, an area where it seems Knowlton was left scratching his head. There is a certain poetic logic in the suggestion that what is needed at such an important impasse is a feminine point of view that intuitively understands the rationale of fooling people with dresses. But the facts culled from all the testimonies resist her solution and still hang there unsatisfied to this day.

A Private Disgrace is a classic entry in the Borden literature and is a “must-read,” even if the crux of her solution is fictional. What makes it a classic? At some point, we have all wanted the macabre legend to be true – morbid as it is for us to think with such a desire. It is as difficult for us as it was for the jury. We are not even barred from any semblance of fact as was the jury—and yet we continually find it difficult. Actually, most of us insist with an almost predictable regularity that this axe-murderess must somehow be made completely plausible as opposed to partially plausible. And what other author ever went to the lengths of Victoria Lincoln in a project to satisfy us? Anyway, good imaginative works are welcome; and who can say whether an intuitive writer might actually “guess” the real solution? Last but not least, and the real point of this critique, is that there are lessons to be learned in Lincoln’s faulty reasoning even for the most experienced readers, debaters, and writers. Important questions are raised about what constitutes objective vs. subjective interpretation of the evidence. Lincoln has given us the kind of problem that includes an opportunity for clearing away confusion and “grounding” us in a respect for the facts.

Works Cited

Lincoln, Victoria. A Private Disgrace: Lizzie Borden by Daylight. NY: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1967.

The Transcripts from the Inquest, the Preliminary Hearing, and the Trial.