by Sherry Chapman

First published in November/December, 2008, Volume 5, Issue 4, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Andrew Borden and his second wife, Abby Durfee Gray, were married on 6 June 1865. At the time of their murders, they had been married twenty-seven years. During those years, according to the Borden sisters, there was only one instance of dissension between their stepmother and themselves.

It is probable that Lizzie and Emma knew that their father had made a will. This they told at the coroner’s inquest:

Q: (by Hosea Knowlton) Did you ever know of your father making a will?

A: (by Lizzie Borden) No sir, except I heard somebody say once that there was one several years ago; that is all I ever heard.

Q: Who did you hear say so?

A: I think it was Mr. Morse.

Lizzie’s answer is confusing. No, she did not know of her father making a will. But she heard her uncle, the brother of her biological mother and still friend, up until his murder, of Andrew Borden, say there was one several years ago.

Did you ever know of your father making a will?

One could take her answer as meaning, “No, I never actually knew he had a will. I never saw a will. But several years back, Uncle John told me he made one. I don’t know if it was true or not. I don’t know if Father actually got around to putting it on paper.”

Did you ever know of your father making a will?

Or, one could take her answer as meaning, “Yes, I knew of him making a will. My uncle, John Morse, told me that there was one several years ago.”

Perhaps that would have been the more appropriate answer.

Here is Emma on the stand at the same inquest:

Q: … Did you ever hear your father speak of a will?

A: No Sir.

Q: Did you understand that he had a will?

A: I knew he had had one, I did not know whether it was destroyed or not.

Q: When was it you understood that he had had one?

A: O, I don’t know, a long while ago.

Q: A number of years?

A: Yes Sir.

Q: More than ten?

A: Well, I don’t know, it seems as if it was longer than that.

Q: How did you get the information that he had a will then?

A: My Uncle, John Morse told me.

Q: That is not the one that is at the house now?

A: Yes.

Q: You did not hear that it had been destroyed?

A: No Sir.

Q: That is, your Uncle John never told you that?

A: No Sir.

Q: Did you know anything of the provisions of the will?

A: No Sir.

Q: It was not before your father married the second time, was it?

A: That my Uncle told me? No, I don’t think it was.

Q: Was it about that time?

A: It don’t seem as if it was as long ago as that, but I am not sure.

Q: You have never heard your father speak of a will?

A: No Sir.

Q: Had you ever talked the matter of the will over with your sister Lizzie? Had you ever talked over the matter of a will of your father with your sister Lizzie?

A: We had wondered if there was one, something like that; that was all.

Q: When, do you recollect, was the last time the subject was mentioned between you?

A: I can’t tell, I don’t know.

Emma was being vague on an irritating level. “I am not sure,” “I don’t think it was,” “I don’t know.” But when it was put to her by Knowlton, “Did you understand that he had a will?” Emma was forthright. “I knew he had had one,” she said. She knew he had had one.

Well, where was it? They did not know. They never heard their father talk about it. Emma mentions the possibility of it being destroyed, though her uncle had never told her that. People change a will frequently, or add codicils. But destroying a will? Maybe one day in a fit of rage, Andrew came stomping down the stairs with papers in his hand. “Wills! Wills are—evil!” and commenced to rip it to shreds and put it in the kitchen stove. Oh no. We could never know that, unless Bridget or a previous servant heard him do it, because his daughters had never heard Andrew talk about a will before. Although much could be said for the thought of one having been destroyed in that kitchen stove.

But why would the sisters worry about what Andrew Borden put in his will? Why would he not give them their fair share? Weren’t Lizzie and Abby at least cordial?

(From the Inquest)

Q: Were the relations between your sister Lizzie and your mother, what you would call cordial?

A: (Emma Borden) I think more than they were with me.

And what was the cause of this? According to both sisters, in 1887, Abby’s stepmother, Jane Gray, decided to sell her half of the house at 45 Fourth Street in Fall River that was handed down to her when husband Oliver Gray died. Abby’s half-sister, Sarah Bertha “Bertie” Gray Whitehead, who was thirty-six years younger than Abby and whom Abby was very close to, had lived in the house all her life. Bertie then had a husband and two young children. Bertie’s second child, George, was born in March of 1887, and the transfer was in May, which meant that her youngest was only three months old.

It was feared that Bertie and her family would lose their home, and Abby appealed to Andrew to buy Jane Gray’s half of the house so her half-sister could retain the home. Andrew bought it and put it in Abby’s name.

When Emma and Lizzie heard what happened, they were angry. They said that what Andrew did for Abby’s people he ought to do for his own. The girls were advised to ask Andrew for a like-property, and he gave them their grandfather Borden’s house at 12 Ferry Street, which allowed them to collect rent from the tenants there.

It was this event that supposedly threw both sisters over the edge. Lizzie stopped calling Abby “Mother.” She would talk ugly about Abby to others and refer to her as “Mrs. Borden” to her face. As near to the murders as the spring of 1892, Lizzie shared some harsh words about Abby to Hannah Gifford, the dressmaker for the Borden women:

(Mrs. Gifford) I was speaking to her of a garment I had made for Mrs. Borden, and instead of saying “Mrs. Borden” I said “Mother” and she says, “don’t say that to me, for she is a mean, good for nothing thing.” I said, “oh Lizzie, you don’t mean that?” And she said, “yes, I don’t have much to do with her; I stay in my room most of the time.” And I said, “you come down to your meals, don’t you?” And she said, “yes, but we don’t eat with them if we can help it.” And that is all that was said.

If Emma disliked Abby more, it is sad to imagine the discontent in the house.

Emma admits on the stand at the inquest that the giving of the property to her and Lizzie did not heal their feelings toward Abby.

“Some weeks” before the murders, as Lizzie testified, Andrew bought the Ferry Street house back from them. He paid them $5,000 for it.

All things should have been well in the Borden household. Andrew gave his wife a half of a house and then he gave his daughters property of better value. And he bought it back from them, even though they never put in a penny toward it. Why, then, would Emma say that their feelings were not healed?

Because it was more than that.

Emma was “just a trifle over fourteen” when Andrew married for the second time. On her deathbed, her mother, Sarah Anthony Morse, told Emma to take care of “Baby Lizzie.” Lizzie was just two years of age when Abby came into the family. Emma had always called Abby “Abby.” But it was not until the property clash, or possibly a year before or after, that Lizzie stopped calling Abby “Mother,” as she had since childhood.

She tells Knowlton at the inquest: “I don’t know that any of the relations were changed. I had never been to her as a mother in many things. I always went to my sister, because she was older and had the care of me after my mother died.”

Some speculate that Emma was the Little Mother of Lizzie. When Abby became their stepmother, Emma could have felt elbowed aside and, worst of all, not able to keep her promise to her real mother. It is good speculation.

Andrew Borden’s estate was worth between $348,000 and $423,000 in 1892 dollars, which would make it worth about $8 million today. It was worth fighting over. Murdering, no. But there are always some who disagree . . .

Abby’s estate is pitiful compared to her husband’s. According to The Boston Globe, Abby’s personal effects were given to her sisters by the Borden girls “shortly after the murders.” However, in Leonard Rebello’s book, Lizzie Borden, Past and Present, page 279, it is stated that on 13 August 1893 the half interest in the house at 45 Fourth Street, Abby’s personal belongings, and bank deposits of $4,000 were transferred to her heirs, Sarah Whitehead and Priscilla Fish. (Note: In Rebello’s book, page 278, a monetary amount of $1,577.67 was not ordered to be disbursed until 2 November 1894, but by this time both Priscilla, Abby’s sister, and George Fish, Priscilla’s husband, were dead.)

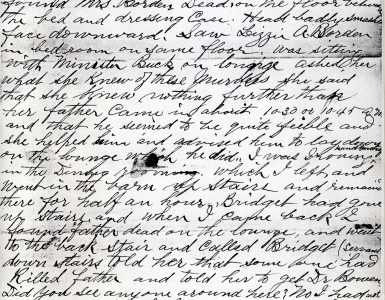

There was something else that was inherited as well. Something that was extremely interesting and possibly overlooked by the Borden sisters. The following comes from the 18 February 1893 issue of The Boston Globe.

IN MRS. BORDEN’S POCKET

__

Bit of Paper Found Which May Be Important

Memorandum That Shows Her Interest

In Mr. Borden’s Property.

Contains List of His Investments in

Local Enterprises

FALL RIVER, Mass., Feb. 17. – Shortly after the murders at the Borden house the wearing apparel and other personal effects of Mrs. Borden were turned over by the stepdaughters to her immediate heirs.

In the pocket of one of the garments a paper was found which is regarded as a significant piece of testimony. The details are set forth in the following, published here in the Globe today:

“Much has been said about the unpleasantness in the family, which arose when Mr. Borden purchased and gave to his wife a half-interest in a small house which was once owned by her father, and it has been maintained that the trifling sum which was paid for the property in question ought not to have caused an estrangement between Miss Lizzie and her stepmother, and that the quarrel which took place was occasioned by some discussion regarding the division of the entire estate.

“Whether this assumption is correct or not may never be known, but there is evidence in existence which gives some color to the suspicion . It is reported that among Mrs. Borden’s effects a memorandum has been found which suggests that at some time or other she was more directly interested in her husband’s property than has been generally supposed. A list, written by her, of some $80,000 worth of stocks in the Troy mill, the Merchants’ Manufacturing Company and other first-class corporations, has been discovered, and that her attention was called to it at a comparatively recent date is proved by the fact that she wrote the word ‘sold’ opposite a certain number of shares in the Globe Street railway company.

“Whether this memorandum was dictated by Mr. Borden is not known, but it is not improbable that he contemplated giving his wife these stocks as her portion of his property, leaving the real estate to be divided between the daughters.

“The list contains substantially a record of all of Mr. Borden’s investments in local ventures. It may or may not have any significance, but it certainly suggests that the money question was discussed occasionally in the household.”

_____

What happened to this piece of paper in Mrs. Borden’s pocket is not known. Somewhere along the line it must have been decided that it proved nothing in a court of law. But Abby’s sisters knew that there was more going on behind that triple-locked front door than most persons knew.

Works Cited:

Burt, Frank H. The Trial of Lizzie A. Borden. Upon an indictment charging her with the murders of Abby Durfee Borden and Andrew Jackson Borden. Before the Superior Court for the County of Bristol. Presiding, C.J. Mason, J.J. Blodgett, and J.J. Dewey. Official stenographic report by Frank H. Burt (New Bedford, MA., 1893, 2 volumes), PearTree Press, Harry Widdows, Stefani Koorey, 2004.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts vs. Lizzie A. Borden; The Knowlton Papers, 1892-1893. Eds. Michael Martins and Dennis A. Binette. Fall River, MA: Fall River Historical Society, 1994.

Inquest Upon the Deaths of Andrew J. and Abby D. Borden, August 9 – 11, 1892, Volume I and II. Fall River, MA: PearTree Press, 2004.

Rebello, Leonard. Lizzie Borden: Past and Present. Fall River: Al-Zach Press, 1999.