by Melissa Allen

First published in Spring, 2009, Volume 6, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

I think everyone has heard the name Lizzie Borden at least once in his or her lifetime. Whether you are an armchair detective on the case, or have simply heard the familiar refrain “Lizzie Borden took an axe,” there is some level of fascination attached to one of the most infamous figures in history. On August 4, 1892, Andrew and Abby Borden were savagely slain during daylight hours in their home on Second Street, a somewhat busy thoroughfare of Fall River, Massachusetts. The weapon was believed to have been a hatchet or a similarly bladed implement. The prime suspect became their daughter, Lizzie Andrew Borden. Abby was Lizzie’s stepmother. Her biological mother, Sarah Morse Borden, had died when Lizzie was two years old. There was believed to be no love lost between Lizzie and the second Mrs. Borden.

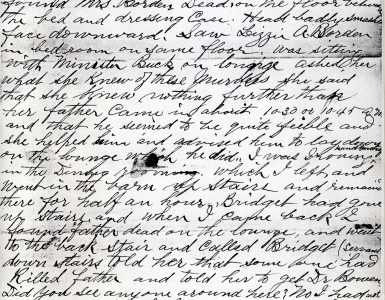

Miss Lizzie had been at home during the commission of both murders. Yet, she claimed she had not heard or seen anything untoward. This fact quickly brought the eye of suspicion to rest firmly on her. She insisted she was in the barn looking for lead to make fishing sinkers when her father was killed, and informed the authorities she believed Abby had left the house after receiving a note to come to the bedside of someone who was sick. This claim was made less credible when a sizable reward offered for the note, or its author, produced no results. Lizzie was arrested and put on trial. This trial uniquely gripped the imagination of the entire country. People from coast to coast were abuzz with their own opinions and theories about “who done it.” In a time before radio, television, or the Internet, the prevailing mode of communication was the newspaper. Reporters from far and wide swarmed to New Bedford, Massachusetts, to provide coverage for their eager readers. A heated climate of clashing opinions existed, and it is said that this actually caused some husbands and wives to file for divorce. Lizzie was ultimately acquitted at the finish of what was labeled the “Trial of the Century.” The State’s case had been almost purely circumstantial. But was she really innocent? Or was it simply the lack of physical evidence to link her to the crimes that made the jury side with her? Maybe Lizzie Borden was acquitted by the all-male jury simply because she was a woman.

I became acquainted with the case in my early teens. After awhile, like other true Bordenites, I became dissatisfied with the “facts” presented in the often-inaccurate books by authors who distorted or even invented information to satisfy their own pet theories. There were so many inconsistencies it made my head spin. What I sought was the plain unvarnished truth of what took place. Twice I made the pilgrimage to spend the night in the house where the murders occurred, now thoroughly restored and known as The Lizzie Borden Bed & Breakfast/Museum. Before checking out after my first visit, I purchased a copy of The Witness Statements from the gift shop. I was pretty excited with my purchase because I had not known such a record existed. What I found contained in that volume excited my interest even further. It was this search for the truth that lead me to the Internet and a most informative, fact-based site about the case, called The Lizzie Andrew Borden Virtual Museum & Library. I found the site during a search for the trial transcripts. I was amazed at the incredible amount of information provided all in one place—everything from the crime scene photographs to the targeted transcripts. I had found a slice of heaven. The members of The Lizzie Borden Society Forum are, in my opinion, some of the most knowledgeable people I have come in contact with concerning all things Borden. There are so many mysteries that crop up concerning the life of Lizzie that it’s great to have the proper arena to discuss them. While boning up on Lizzie’s later life at Maplecroft in the archives of the site, I found a new puzzle, minus a few key pieces.

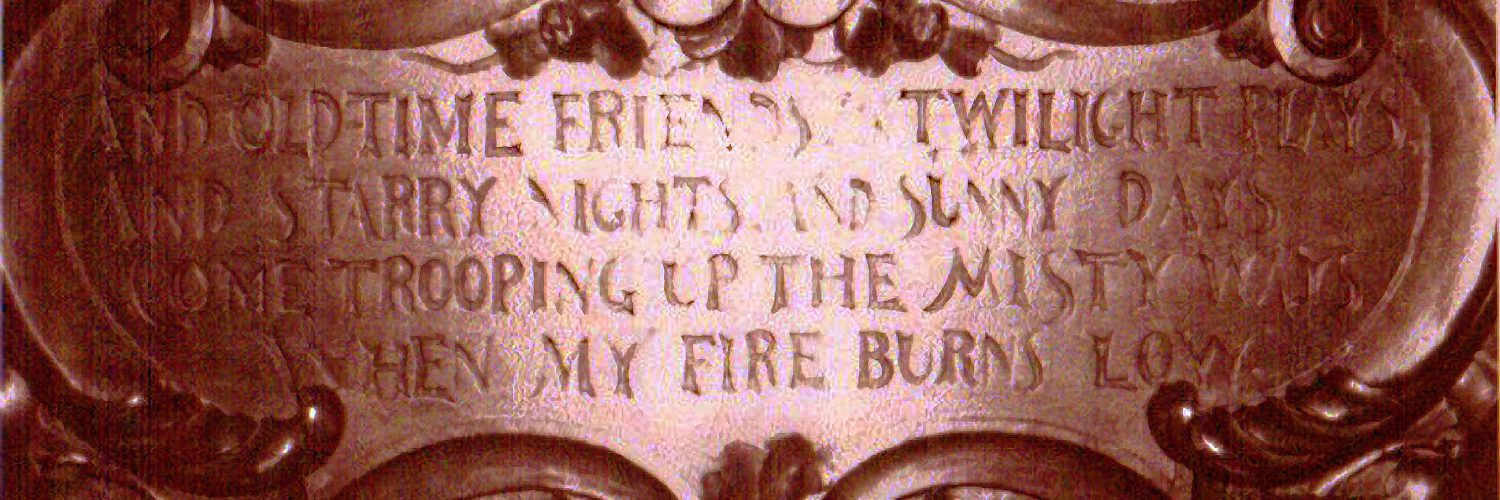

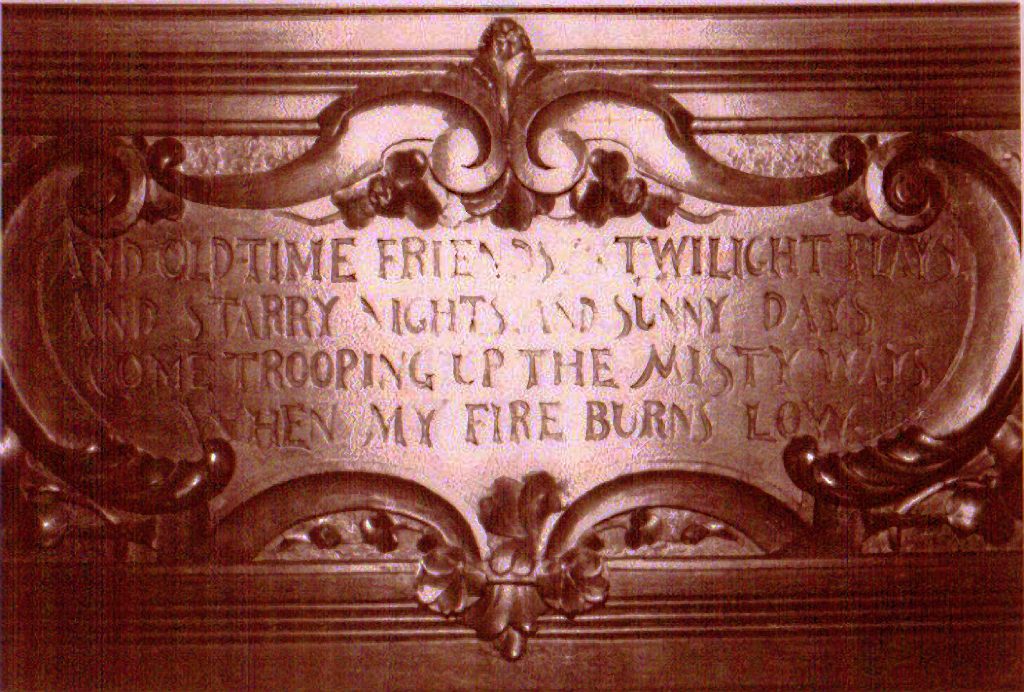

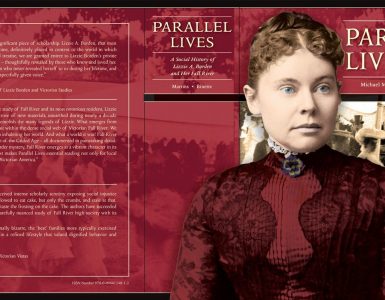

After Lizzie’s acquittal, she and Emma moved to a more fashionable house on French Street. We know precious little about how she spent her remaining years. Most of the reliable accounts come from her few loyal friends, her equally loyal servants, sketchy news reports, and family members. There is also very little in the record of how the new estate, dubbed Maplecroft, came to be decorated in the style in which it was found upon her death. It was definitely a step up from the two-story Greek Revival house on Second Street. By the time of her death in 1927, the house had fourteen rooms, which included winter and summer bedrooms for Lizzie. One mystery centered on the carvings that adorned two elaborate fireplaces inside Maplecroft. Both mantel carvings contained poems that were very lovely, and seemed to speak of a yearning for the past. It is not known for certain if Lizzie had these inscribed herself, or if they were the work of a previous owner. The author of this mantle poem was unknown until recently:

And Old-Time Friends & Twilight Plays,

And Starry Nights, And Sunny Days,

Come Trooping Up The Misty Ways

When My Fire Burns Low.

I gained a new fascination for the search to find the origins of these few haunting lines. I discovered that one member of the Lizzie Borden Society Forum, William Ulrich, had already done his own extensive research into the carvings, which was published in 1995, in the Lizzie Borden Quarterly. His research was impressively thorough, carrying many detailed descriptions about the interior of Maplecroft. He was kind enough to send a copy of this article to me. William describes a most opulent atmosphere at French Street, the likes of which were unmistakably absent from the house on Second Street. He wrote, “The house, an elegant turreted, three-story, Queen Anne Victorian, contained fourteen rooms and four bathrooms—a far cry from the single privy on Second Street!” Was this a motive for murder? His exceptional probing, unfortunately, did not lead him to the author of those four elusive lines.

The carvings are also mentioned in Leonard Rebello’s book Lizzie Borden Past and Present. On page 325 we find, “Note: The author of the above line of poetry or poem is unknown. Research at the New York Public Library, Boston Public Library, Harvard University Library and Fall River Public Library was unsuccessful.” As determined as I was to investigate, the task seemed pretty hopeless. If these great minds had already delved into the mystery only to come up empty handed, who was I to think I would fare any better? My research consisted of combing libraries, yard sales, flea markets, eBay, antique shops, and any other place that might carry an old volume of poetry. The Internet was another endless source of information that led . . . nowhere. Direct searches for the poem often resulted in inane references to things totally unrelated. Newspaper archives containing poetry submissions were also a bust. It was surmised by some that the lines could have come from an old Irish or Scottish hymn. I searched musical references and even limericks. Frustration was the high point of my research.

One day I decided to search Google Books. This search tool has been immeasurably useful to me in a variety of ways. First I scanned “Victorian poetry.” After reading until my eyes crossed, I tried several other search tactics. Then I tried typing in the phrase “and old time friends and twilight plays.” And there it was. I blinked and just stared at the page. Surely it couldn’t have been that simple. After probing all those musty pages of moldering poetry and endless online searches, after all the time spent by me and countless others researching, I had simply “Googled” it up? It sounds almost a bit laughable. What I had found was a poem included in Common-School Literature English and American with Several Hundred Extracts to be Memorized (1876), by James Willis Westlake, page 149:

CCXLIV

When klingle, klangle, klingle,

Way down the dusky dingle,

The cows are coming home;

How sweet and clear and faint and low

The airy tinklings come and go,

Like chimings from the far-off tower,

Or patterings of an April shower

That makes the daisies grow;

Ko-ling, ko-lang, ko-linglelingle,

Way down the darkening dingle,

The cows come slowly home;

And old-time friends and twilight plays

And starry nights and sunny days

Come trooping up the misty ways,

When the cows come home.

After a few more inquiries, I learned that this was a poem written by Agnes E. Mitchell and is entitled “When the Cows Come Home.”

1

With klingle, klangle, klingle,

‘Way down the dusky dingle,

The cows are coming home.

Now sweet and clear, and faint and low,

The airy tinklings come and go,

Like chimings from some far-off tower,

Or patterings of an April shower

That makes the daisies grow.

Ko-kling, ko-klang, koklinglelingle,

‘Way down the dark’ning dingle

The cows come slowly home;

And old-time friends and twilight plays,

And starry nights, and sunny days,

Come trooping up the misty ways,

When the cows come home.

2

With jingle, jangle, jingle,

Soft tones that sweetly mingle,

The cows are coming home.

Malvine, and Pearl, and Florimel,

De Kamp, Redrose, and Gretchen Schell,

Queen Bess, and Sylph, and Spangled Sue —

Across the fields I hear her loo-oo,

And clang her silver bell.

Go-ling, go-lang, golinglelingle,

With faint far sounds that mingle,

The cows come slowly home;

And mother songs of long-gone years,

And baby joys, and childish tears,

And youthful hopes, and youthful fears,

When the cows come home.

3

With ringle, rangle, ringle,

By twos and threes and single,

The cows are coming home;

Through violet air we see the town,

And the summer sun a-slipping down;

The maple in the hazel glade

Throws down the path a longer shade,

And the hills are growing brown.

To-ring, to-rang, toringlelingle,

By threes and fours and single,

The cows come slowly home;

The same sweet sound of wordless psalm,

The same sweet June-day rest and calm;

The same sweet scent of bud and balm,

When the cows come home.

4

With a tinkle, tankle, tinkle,

Through fern and periwinkle,

The cows are coming home;

A-loitering in the checkered stream,

Where the sun’s rays glance and gleam,

Starine, Peachbloom, and Phoebe Phyllis

Stand knee-deep in the creamy lilies,

In a drowsy dream.

To-link, to-lank, tolinklelinkle,

O’er banks with buttercups a-twinkle,

The cows come slowly home;

And up through Memory’s deep ravine

Come the brook’s old song and its old-time sheen,

And the crescent of the silver queen,

When the cows come home.

5

With a klingle, klangle, klingle,

With a loo-oo, and moo-oo, and jingle,

The cows are coming home;

And over there on Merlin Hill,

Hear the plaintive cry of the whip-poor-will;

The dewdrops lie on the tangled vines,

And over the poplars Venus shines,

And over the silent mill.

Ko-ling, ko-lang, kolinglelingle,

With a ting-a-ling and jingle,

The cows come slowly home.

Let down the bars; let in the train

Of long-gone songs, and flowers, and rain;

For dear old times come back again

When the cows come home.

I believe one reason the origin of the carving was never discovered was because the last line had been changed from “when the cows come home” to “when my fire burns low.” This could have been a big obstacle considering most people I have talked to refer to the poem as “When My Fire Burns Low.” Another hindrance to discovery could have been that Mrs. Mitchell’s poem seems to change like a chameleon from one publication to the next, containing anywhere from 6 stanzas to a whopping 75. It appears in everything from English textbooks, to prayer books, to ladies magazines. It seems to have been a very popular aid in elocution lessons for young Victorian ladies.

Still another conundrum is that the lines from the carving are not included in some versions. Why there are so many deviating forms is anyone’s guess. Mrs. Mitchell proves to be an elusive figure. Kentucky in American Letters, 1784-1912, by John Wilson Townsend and Dorothy Edwards Townsend, states, in part, “Dr. Henry A. Cottell, the Louisville booklover, is authority for the statement that Mrs. Agnes E. Mitchell, author of ‘When the Cows Come Home,’ one of the loveliest lyrics in the language, lived at Louisville for some years, and that she wrote her famous poem within the confines of that city. The date of its composition must have been about 1870. Mrs. Mitchell was the wife of a clergyman, but little else is known of her life and literary labors.” The Encyclopedia of Louisville, published in 2001, also adds, “Agnes E. Mitchell wrote ‘When the Cows Come Home,’ about 1870, not suspecting that her title would become a household phrase.” Some references have also been made to her residing in Michigan.

But did Mrs. Mitchell write the poem in question? If my research is correct, Mrs. Mitchell wrote the poem around 1870. But there are sources that claim an Agnes E. Mitchell was born in 1862-63. Is this our poetess? If so, could she have written the poem when she was just 8 years old? It seems I’ve uncovered even more questions in my quest. But I guess it would be safe to assume that in this day and age, whatever the mystery you are trying to uncover may be, most things can be successfully “Googled.”

Works Cited:

Crane, William Iler, and William Henry Wheeler. Wheeler’s Graded Literary Readers with Interpretations: A Sixth Reader. Chicago: W.H. Wheeler & Company, 1919: 56-58.

Kleber, John E., ed. The Encyclopedia of Louisville. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001, p. 710.

Rebello, Leonard. Lizzie Borden Past and Present. Fall River: Al-Zach Press, 1999: 325.

Townsend, John Wilson, & Dorothy Edwards Townsend. Kentucky in American Letters 1784-1912. Vol. 1. Cedar Rapids: Torch Press, 1914, p. 385.

Ulrich, William. “The Carvings of Maplecroft.” Lizzie Borden Quarterly II.6 (Winter 1995): 1, 3.

Westlake, James Willis. Common-School Literature English and American with Several Hundred Extracts to be Memorized. Philadelphia: Christopher Sower Co., 1876: 149.