by Michael Brimbau

First published in May/June, 2006, Volume 3, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

With the advent of the Internet, bookstores all over the country have been forced to adapt their business practices to suit the new demands of the electronic book market. This could be a good or bad thing, as older Antiquarian bookstores and senior booksellers rush to educate themselves about the countless outlets now offered for consignment of their stock.

Unfortunately, and perhaps as a direct result of the Internet, many small Antiquarian bookstores have closed their doors in the last ten years. Unless the proprietor is the owner of the building in which he has a store, he is finding the financial restraints more shackling than ever. This began when the walk-in customer chose to leave his coat and hat at home in exchange for the comfort and convenience of the easy chair and the computer, where he can browse the bookstores of the entire world. Before the Web, it may have taken a serious collector many years of scrubbing local bookstores and book shows to find that illusive title. Now, without leaving the den, one can amass a collection in a couple of months that would have previously taken a lifetime.

Some dealers have made the change by rolling with the times and converting their inventories into an Internet book site. Sellers are discovering that they no longer need a conventional shop, since they can make business more profitable by working from home. Unfortunately, the book wanderer or collector wishing to handle, stroke and caress his favorite title is finding he must settle for the impersonal book depot outlet, or generic mall bookstore, if he wishes to feast with his hands.

In the mid 1990s, two precious gems, A Taste of Honey Bookstore and The Bookhaven, Fall River’s mainstay Antiquarian bookstores, closed their doors. They were located side by side in the 1700 block of North Main Street. Anyone looking for a Radin, Spiering, Pearson, or Porter could find it in either one store or the other. Ralph Roberts, proprietor of The Bookhaven, had a nose for flushing out wondrous collections that left a young book lover intoxicated and salivating with curiosity. The sloping bookshelves, dim lighting, and musty smell of fermented paper permeated the air in these small institutions—the smell of home for a book lover.

Each shop had a Local History shelf, kept behind the desk or close to the counter where the clerk sat reading a newspaper and nursing a muffin and coffee. This is where the common and rare Lizzie Borden books were kept. One could go behind the desk at The Bookhaven but Jim McKenna did not allow this practice at A Taste of Honey. At The Bookhaven, one merely squeezed by, reached over, grabbed a title, and tried not to spill the attendant’s drink. If it was behind the counter at A Taste of Honey you had to ask for it and it was gladly handed to you.

Because A Taste of Honey was a modest place, not much larger than the average household bedroom, you automatically became intimate with those inside. The size of the place left you little choice. While browsing you could not pass on any secret book tips to your companion—even a whisper would not go unheard. When you entered this tiny conservatory of books, Jim would greet you with a benevolent smile. The counter where Jim orchestrated his sales was on the right, just as you entered the door. Most times Jim could be found just browsing his own shelves, and be easily mistaken for a customer. Books encompassed the entire free space, from wall to wall, ceiling to floor. The place had an Alice in Wonderland mystical quality to it, a funhouse of books, and as you walked its spongy floor something of interest could always be discovered. The first things to impress you were the shelves. Almost all sagged terribly with the weight of the books, forming the appearance of a smile with its teeth of books. The crooked shelves that circled the room all appeared ready to come down at any moment. Even though the shop was tiny, a rarity, such as a book once owned by Lizzie and signed by her inside, could occasionally be found and sold—for $750.

Jim was one of the few book dealers in the area who offered a paperback book exchange program, which was a boon to some of the older folks who had to balance their expenditures for prescriptions with book money.

The Bookhaven was an old dusty place with a tall Victorian ceiling of stamped steel, peeling painted walls and a large glass storefront that faced North Main Street. Little had changed since it was built around the turn of the century or when Lizzie was alive. It was almost eight times larger than its rival next door. As space became a premium, books were stacked along the walls, under tables, and on the floor along the aisles. Some were never removed from the cardboard boxes they arrived in, leaving customers to rummage about. It was not the best-kept shop, but at times you could make a rare find, one that everyone else missed.

Sadly, both The Bookhaven and A Taste of Heaven have closed their doors. Ralph still resides at his Fall River home on the Hill. After he closed his shop he occasionally sold books at his home and by appointment. Now, Ralph Roberts would be in his middle eighties. James McKenna died some years ago. Both men are remembered fondly, like the books they sold. And so, quietly, an era in Fall River history passes in a twinkle, almost unnoticed.

The Quest for Porter

Searching for books to add to my collection in the early 1980s was both a struggle and a pleasure, involving much footwork to locate a certain scarce title. The adventure of the hunt and the delight of discovery were always sweet, whether it was a book show at Clark University in Massachusetts, or a leisurely ride to Titcombs Book Store in Sandwich on Cape Cod. To me the sensation behind opening the door and hearing the little bell chime above my head was akin to a child entering an amusement park and hearing the roar of the roller coaster as it clanged across the tracks.

These little bookshops used to litter the New England countryside. Many were in old barns, some in small extensions off the main house, and a few were right inside the dealers home, where he would offer you a cup of coffee or a coke while you browsed—you could not get much better then that.

These little bookshops used to litter the New England countryside. Many were in old barns, some in small extensions off the main house, and a few were right inside the dealers home, where he would offer you a cup of coffee or a coke while you browsed—you could not get much better then that.

Once I had found that precious copy I always wanted, I would spend time occupying the dealer’s parking lot, as I thumbed through my buys. I may have spent just five dollars or a couple of hundred, garnered one book, or a large bag full. I would not be able to start home without inspecting them. Being a lover of almost any sort of book, I have been the victim of many odd glances as I pulled the books out one by one and brought them to my nose. I dared toy with the idea that I could almost tell what year they were published by the sweet musty smell. The trip home was always accompanied by a broad smile. Of course today that has changed drastically. Most recent Lizzie titles are easily found, paid, and shipped with the press of a few keys on a keyboard.

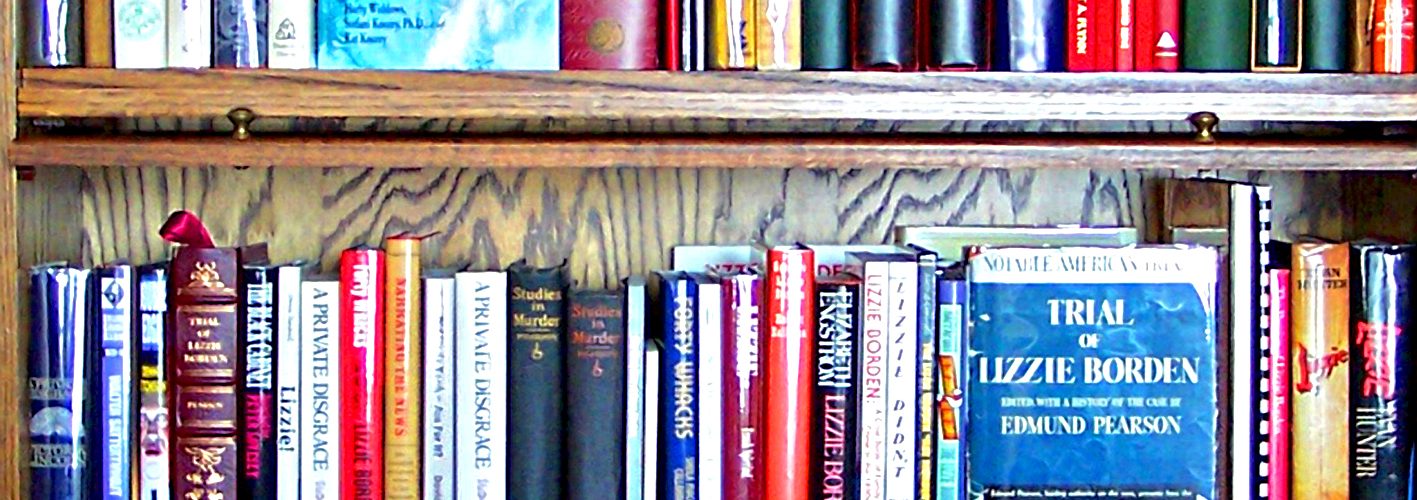

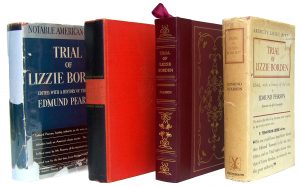

Marie Belloc Lowndes’ book, Lizzie: A Study in Conjecture, was the first acquisition to my Lizzie book collection. Though it lacked a dust jacket, I was happy to pay Jim at A Taste of Honey the $22 to possess this little morsel back in 1982. Jim always had something of interest to offer. At that time, the choice of materials for Borden studies was drastically less than they are today. For the first sixty-eight years following Edwin Porter’s The Fall River Tragedy, one had to reconcile himself to Edmund Pearson’s Trial of Lizzie Borden or Lowdnes’ aforementioned Conjecture. Even copies of Pearson’s Murder at Smutty Nose and Studies in Murder were difficult to locate, and when found, went for a premium fee. Also, paperback copies of the 1953 first edition of Charles and Louise Samuels’ The Girl in the House of Hate appeared to have vanished.

I spent countless hours in both The Bookhaven and A Taste of Honey book stores. I would see people from as far away as Maine and Connecticut come in asking for a copy of Pearson’s Trial of Lizzie Borden. Many times they would have to settle instead for Victoria Lincoln or Edward Radin’s book, which appeared to be fan favorites. Lizzie Borden sells well in Fall River.

One day I was browsing the window of The Bookhaven. Books were left there to bake and bleach in the sun, their covers curling like potato chips. Inside, I could see Ralph Roberts waving and beckoning me to enter. Suddenly, I heard an intermittent hissing noise. I turned to see Jim McKenna, owner of A Taste of Honey, lurking in the doorway of his shop competing for business. I knew that when Jim wiggled his finger he had something good to show me. It was not long before I realized that both shop owners practiced Jim’s method of getting a regular customer’s attention. Lizzie collectors are like hungry bass in a barrel. Both Jim and Ralph were experts at quickly reeling you in.

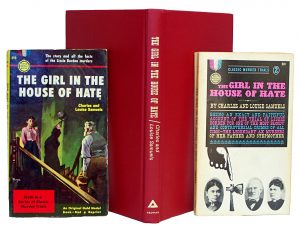

That day that Ralph called me over, I purchased my first copy of Charles and Louise Samuels’ The Girl in the House of Hate (1953) edition in paperback. This was the first real American edition of this title, published by Fawcett. To a diehard collector, a true first edition is, of course, the most desired. Nine years later Fawcett would reissue the book, once again in paperback, with a new cover illustration not as interesting as the first. It was not long before another issue, this time in blue cloth hardcover, was published by Aeonian Press and limited to 300 copies. True limited editions are also collectable and generally increase in value over time because once the allotted number in the edition is printed, there should be no others using similar print, paper, or format. At times, a publisher may announce that a printing is limited to a certain number but make no account of it in the book. This is an acceptable practice. Yet inexplicably, there exists a red cloth covered “limited edition” Samuels on the market. Inside it says that it is also limited to 300 copies, but it is exactly like the blue cloth true limited edition in every way but the color of the cover. A second printing should change more than its cover to be considered authentic. One can only assume that this red covered copy is rather a reprint of the limited edition, and has no collectable value. This copy should be purchased to be read, not as a collectable with any lasting value.

It was not until 1961 with the appearance of Edward Radin’s book Lizzie Borden, the Untold Story (Simon & Schuster), that a modern popular book was published on the Borden murder case. Radin was a maverick in his investigation and ultimate conclusion that Lizzie was innocent of both murders. He was brazen enough to take on Edmund Pearson’s established finding of Lizzie’s guilt, breed new life into credulous minds, and dare question what had always been the common acceptable doctrine—that Lizzie had gotten away with murder. Radin opened the floodgates, and in the latter part of the 20th century countless students, writers, enthusiasts, both expert and novice, would give birth to their own accounts of fact and fiction. Many took liberties with the facts in expressing their point of view, no matter how outrageous or peculiar they might have seemed.

It was not until 1961 with the appearance of Edward Radin’s book Lizzie Borden, the Untold Story (Simon & Schuster), that a modern popular book was published on the Borden murder case. Radin was a maverick in his investigation and ultimate conclusion that Lizzie was innocent of both murders. He was brazen enough to take on Edmund Pearson’s established finding of Lizzie’s guilt, breed new life into credulous minds, and dare question what had always been the common acceptable doctrine—that Lizzie had gotten away with murder. Radin opened the floodgates, and in the latter part of the 20th century countless students, writers, enthusiasts, both expert and novice, would give birth to their own accounts of fact and fiction. Many took liberties with the facts in expressing their point of view, no matter how outrageous or peculiar they might have seemed.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, it appeared that Radin was the most sought after read at both A Taste of Honey and The Bookhaven. Pearson’s Trial was now approaching $50, placing it in the ranks of serious collections. But Lizzie Borden, The Untold Story was very affordable at $15-22. Victoria Lincoln’s A Private Disgrace ran a close second to Radin’s book in terms of popularity, and cost about $22-28. At the time, these titles could be purchased for a lot less anywhere but in Fall River. Radin and Lincoln’s books were my third and fourth acquisitions.

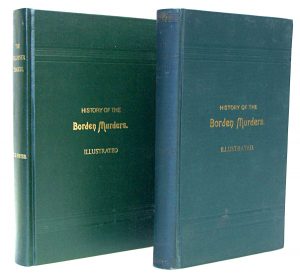

Now my compass was set on locating an original first edition of Edmund Porter’s The Fall River Tragedy. I figured if I hung around long enough and visited The Bookhaven or A Taste of Honey often enough, one was bound to show itself. Finding an 1893 first edition of Porter was thought to be all but impossible. It was believed that there were only three or four in existence because Lizzie had somehow destroyed almost all copies—or had she?

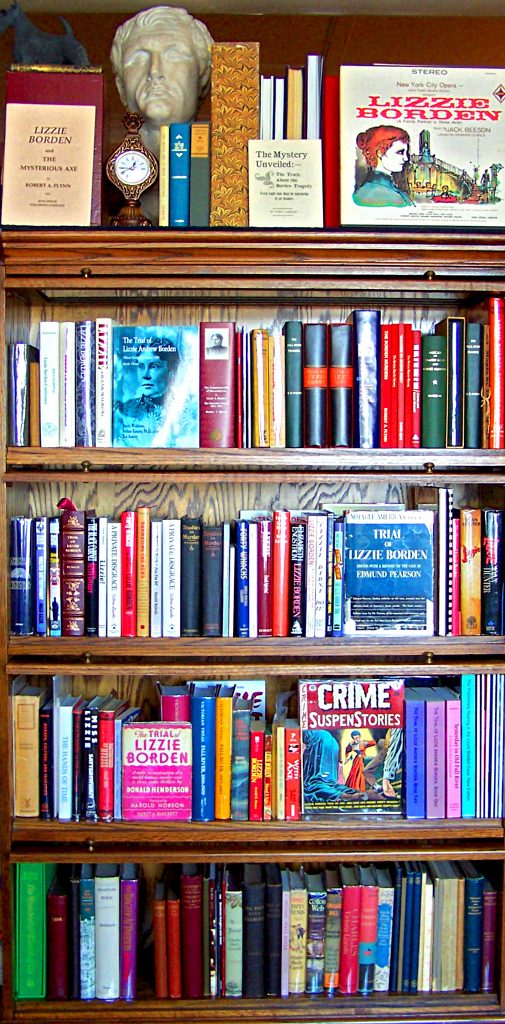

A first edition Porter makes for a truly rare cornerstone to any BiblioLizzieac’s collection. The only other Lizzie related book that holds more value is the small 56 page pamphlet-size book titled The Mystery Unveiled by phantom author Todd Lunday (1893, J.A. & R. A. Reid Publishers). In an unusual approach, the author sets forth the details of the crime in a reasonable and logical progression of facts, but concludes that because Lizzie was the only suspect and was acquitted, and he has proven that no outside agent could have done it, no murder was committed. Robert Flynn, who owns King Philip Publishing, provided a facsimile reprint of Porter’s book in 1985, and had the use of an original Lunday, once owned by City Marshal Hilliard, to create and publish a facsimile reprint of this booklet in 1990. Even this Lunday reprint, which is limited to 1000 copies, is demanding good value on dealer book sites, sometimes seen for sale from $60-100. Flynn is currently selling his last remaining copies of his Porter reprint on eBay for $125, although one can usually find this book for a bit less if you have patience.

Robert Flynn would often be seen at Taste of Honey or Bookhaven, and it was probably at Taste that he picked up his Porter original. I remember several times seeing Flynn with some precious items under his arm as I came strolling into the shop. I would always kick myself for not getting there a few minutes earlier. Ralph, Jim, and Robert Flynn were all well acquainted and both shop owners would squirrel away rare items for Flynn. Such were the loyalties amongst book dealers. This was a world a collector only caught a glimpse of now and then. I always found this practice odd, since there were collectors who were ready to pay a premium for what Robert Flynn had purchased at a bargain. However, Jim and Ralph were not major buyers or sellers, nor did they care to be. They were happy as clams in their own little Fall River book pond. But whatever we may think about Robert Flynn’s bargains, it is good to see he put them to good use with his marvelous reprints.

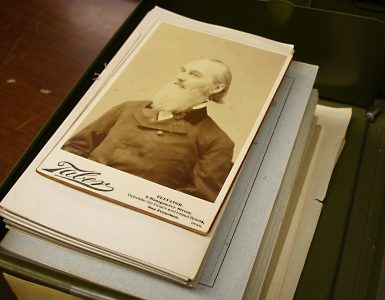

John D. Munroe, a small modest job printer in Fall River, first published Edwin Porter’s book. They were known for producing small press printings for local businesses and churches, such as Lizzie’s Central Congregational Church or the First Baptist Church, which was located across from the YMCA on North Main Street. The Munroe Press had their offices at 21 Bedford Street and later at 28 Bedford. In February 1928, Munroe, along with almost twenty buildings encompassing seven city blocks, were burned to the ground in a devastating fire that destroyed most of Fall River’s downtown business district. Munroe then moved to 107 Borden Street.

I have always felt that it was an error in judgment on Edwin Porter’s part to choose a small local publisher such as George R. H. Buffinton, who was manager of the Fall River Daily Globe, and the press of J. D. Munroe. I could never reason why Porter did not shop for a major New York or Boston publishing house, a publisher with national distribution. It is difficult to believe that a story that generated such international publicity could not stand on its own merits and sell thousands of copies. Though crime fiction was a good seller in the late 19th century, true crime was not, but then this was not your average true crime story. If Porter could have found a publishing firm with national distribution, he might have become a very wealthy man.

Did Lizzie destroy most of the copies of this book? William Schley-Ulrich noted in the October 1997 issue of The Lizzie Borden Quarterly that there are 42 reported copies and 36 verified copies present and accounted for yet I am sure there are other copies in unknown private libraries and the actual number may never be known.

Why Edwin Porter did not just run out and publish a completely new second edition is a conundrum. One is left to conclude that Porter must have been paid off not to print any new copies. If you wish to make it more interesting, you can easily surmise that Lizzie met with Porter who came to sympathize with her tale of innocence, and in kind, abandoned his endeavor, after receiving a handsome offer of course. Some have even speculated that since Porter became seriously ill over the years he lost all interest in his pursuit (Porter died at 39). Of course, I make no conclusions, you understand. Like many aspects of this case, I believe the real answer will always be an enigma.

Spending countless hours in both Bookhaven and Taste of Honey, enough to be more familiar with the stock than their owners, I became certain that ownership of an 1893 copy of Porter could be realized. Jim and Ralph had both reported to have seen, and even own, copies in the past. Moreover, the 1979 edition of The Book Collector’s Handbook of Values by Van Allen Bradley, which Ralph kept hidden in his desk, listed Porter’s 1893 first edition as having a value of $50-60. With this information, I concluded that there must be some unknown copies that survived and Lizzie did not get to all of them as once believed. This, of course, was before the publication of Frank Spiering’s account in his book Lizzie (1984) in which he made popular the claim that only four copies of The Fall River Tragedy were known to exist.

Then, one cold dusky winter evening, I was driving home from work and noticed that Bookhaven was open later than usual. Ralph had just received a large shipment of books, another of his marvelous finds, containing a large art collection, mostly of French Impressionism, Degas, Cezanne and Manet. Among them were over 200 pristine slip-cased Heritage Press Classics and a sprinkling of first editions. As with Andrew Borden and his inroads into real estate deals, Ralph was a lawyer by profession and had his own connections to estate settlements and liquidations. From this came books—thousands of them. Sadly, this usually meant someone had died, and all their precious treasures and painstaking collections were to be broken up and scattered among the masses.

I found Ralph kneeling among a pile of books, working in the dim florescent light. The long grey tubes flickered and hummed, throwing a shadowy, bleary light that burned the eyes. He looked up, his glasses hovering on the tip of his nose, a pencil in his mouth. Without saying a word he waved a finger to the shelf containing local history and went back to pricing a stack of books. Once again, the wiggling finger meant go, investigate and discover.

And there it was—a Porter, tucked tightly between McAdam’s The Commonwealth and a ragged copy of Radin lacking its dust jacket. I gingerly tugged at its soiled green binding. The pine shelf creaked and reluctantly gave up its resident. I was both elated and disappointed. I finally had a Porter in my hands, but the condition was deplorable. It was filthy, the binding was cocked, and it looked like an elephant had sat on it and proceeded to scratch his bottom on the cover. I carefully opened the front board. The book creaked and crackled as if crying out in pain. It was so stiff that I had to use both hands to slowly pry it open, afraid I would damage it further. Someone had glued the cloth back cover on the book, and, in doing so, had glued the binding to the pages at the spine where the signatures all met. The end papers were detached and lay in the book loosely. Acidity had ravaged the parchment, and left the pages the color of coffee. If not careful, you could fold over a page and it would snap like a piece of raw spaghetti. Over the years, I would soon discover that most copies of the book were not found in much better condition. Porter’s book was a title well read and passed around. Due to its construction, time has not been very kind to it. Still, as I stood there thumbing through its fuzzy and gruesome photographs, I felt that I was holding the dead bodies of Andrew and his wife in my hands.

Ralph shuffled over with a stack of books cradled in his arms. The pile toppled onto the desk sending pencils, paper clips and books all over the place.

“Better hang onto that Michael. You’ll never see another,” he declared, ignoring the mess that now lay all over the floor. He had assured me in the past that copies would turn up, and like a true bookman, this copy was now one of a kind. I pondered his claim.

“How much Ralph?” He turned and snatched the book from my hand. Placing it on the table in front of him, he spread the boards apart like he was setting a bear trap. The binding screamed out. I cringed.

“I’ve got to get a hundred fifty,” he mumbled, the pencil still in his mouth. I thought long and hard. However, in the book collecting game condition is everything, and he who hesitates is, well, we know how that goes. But, this was a very rare book. What to do . . . what to do? “Will not be here long,” he announced, as he penciled in the price on the inside cover. He shuffled away and returned the Porter to its station on the shelf.

“I’ll think about it Ralph,” I responded. Walking back, he leaned over and poked me with the pencil.

“One twenty five,” he whispered, “but that’s if you take it today.”

Once again, I said I would think about it. Two days later, it was gone.

Time passed and sure enough later in 1983, another copy came up for sale. This time at an antique auction, held every Thursday night at the Elks Lodge in Fall River. This copy was just as bad as the last. The boards were completely detached and the green flowered end papers were missing. Later that night with the book held high, the hammer dropped. “Sold!—for $400 to the gentleman in the back of the room.” It was not me. Two Porters in two years, not bad odds, I thought to myself. There will be others. Now, I was sure, the old girl had missed some.

Mr. Schley-Ulrich’s proof that 36 copies exist was a belief that I had always subscribed to. If Lizzie had indeed purchased the entire printing, I was sure a clever employee at Munroe would have walked off with a couple. Over the years I have handled six copies: one at Bookhaven, one at a Fall River auction, one at the Boston Book show, and two at the Fall River Historical Society. Then in 1985, I attended a book show, one of many over the years, on Cape Cod. It was there that I discovered my Porter. Yes! There it was on a dealer’s shelf standing straight out and tall like a proud soldier.

I gingerly removed it from the shelf and like a newborn baby gently cradled it in my hands. The binding was clean and bright. Though the spine lettering had long faded, it was a fresh clean copy. I opened the book and found that even in this fine copy, the papers were brown and dull. Amazingly, it was wrapped with the remnants of an old plain brown dust jacket. There was not much left of it though, only one inch of the spine of the jacket survived and on the cover, it read Altwood Co., New York. A previous owner had placed this on the book. But the jacket had been with the book almost all its life and credited with protecting the binding for those many years. Thus, this volume was in marvelous condition.

The book dealer stood close behind me, garnishing a proud smile. “Won’t find another,” he declared. All the time I held this treasure, he watched me like a cat on a mouse. I turned to him, lifted the book up, and cocked my head. To this he responded, “$500.” I handed him the book and reached for my checkbook. His smile broadened. “Would you like a bag?” he asked.

“Two bags please,” I said. That was a happy day. It would have been a glorious day for any Lizzieac.

That same year Robert Flynn published his facsimile reprint, and I purchased two copies from him at another book show. Under a table that displayed history books on Maine and New England, he had a copy of Pearson’s 1937 book in a very good dust jacket. I stooped down and pulled back the tablecloth to get a better look. Pearson’s book, The Trial of Lizzie Borden, in a dust jacket! Wow! They were scarce in a jacket and I had never seen one.

“How much for the Pearson?” I asked.

He quickly snatched the book, placed it into a box under another table, and threw his jacket over it. “Sorry, not for sale.”

Along with the six copies of Edwin Porter’s Tragedy that I have handled over the years, I have seen two more copies on eBay, and three copies on the Abebooks.com website. Of the copies for sale on Abe, one copy was $600, one $800, and one $1200. They all have since been removed, and I can only assume that all have been sold.

In friendly banter, I would needle Jim McKenna about whether he owned a copy of Porter’s book. Jim never admitted whether he did have an 1893 Porter at home. I always wanted to compare his copy to mine. Every time I would inquire, he would display a sheepish smile and walk away. It is a discovery I never made. Jim was a gentleman.

In friendly banter, I would needle Jim McKenna about whether he owned a copy of Porter’s book. Jim never admitted whether he did have an 1893 Porter at home. I always wanted to compare his copy to mine. Every time I would inquire, he would display a sheepish smile and walk away. It is a discovery I never made. Jim was a gentleman.

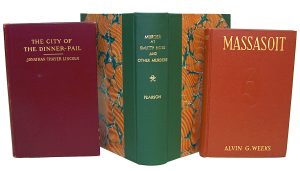

From Jim’s shop, A Taste of Honey, I purchased titles such as Fall River and Its Industries (1877), Barbara Hunt’s Cotton Web (1958), a scarce novel centered on the Fall River textile industry by a British author and published by MacDonald in London (I have never seen the American edition). Add to that Pearson’s Trial of Lizzie Borden, along with his Murder at Smutty Nose and Studies in Murder, not to mention countless other books, postcards, and ephemera.

From Bookhaven came: Massasoit of the Wampanoags (1919) by Alvin Weeks, a short history of the Wampanoags; most of Roger Williams McAdam’s books on the Fall River line; and Jonathan Thayer Lincoln’s City of the Dinner Pail (1909), a non-fictional account of life within the mills in Fall River. His daughter, Victoria Lincoln, went on to write A Private Disgrace and February Hill, the latter centering on a family and their exploits in Fall River. Though known to Lizzie fans mostly for her book on the Borden murders, February Hill went on to be Victoria Lincoln’s biggest money-maker and most famous title, having been made into a play, Primrose Path, and later into a movie starring Ginger Rogers.

From Bookhaven came: Massasoit of the Wampanoags (1919) by Alvin Weeks, a short history of the Wampanoags; most of Roger Williams McAdam’s books on the Fall River line; and Jonathan Thayer Lincoln’s City of the Dinner Pail (1909), a non-fictional account of life within the mills in Fall River. His daughter, Victoria Lincoln, went on to write A Private Disgrace and February Hill, the latter centering on a family and their exploits in Fall River. Though known to Lizzie fans mostly for her book on the Borden murders, February Hill went on to be Victoria Lincoln’s biggest money-maker and most famous title, having been made into a play, Primrose Path, and later into a movie starring Ginger Rogers.

The books in these shops were like endless travelers on a literary voyage. They would arrive from all over the New England countryside, sit, wait and then vanish in the company of new custodians, where they would reside in libraries, until their next journey to a new distant place. Within the ever-evolving connections of the book market, it could be halfway around the world. Many of these books, I dare say, will cross oceans several times, especially today, with such computer book sites as Abebooks.com, Amazon.com, Alibris.com, TomFolio.com, and of course, eBay.com. Who could predict twenty years ago that I would be finding some of my titles in such places as the UK, Israel, South Africa or Australia?

In the 1980s, if you were in search of a scarce title, you would have to attend book shows, collect dealer names, and ask to be placed on their dealer customer list. If it were a Lizzie Borden related title you were searching for, your best chance at that time would have been to befriend one of these dealers, preferably a New England dealer.

All this has now changed. Competition in the field is very keen. In the 1980s, a copy of Pearson’s Trial of Lizzie Borden was selling in Fall River (at A Taste of Honey) for $50-65. Since the advent of the Internet, many unknown copies have been flushed out onto the book market, making the book no longer scarce. At the time of this writing, there are eleven first edition copies of Pearson’s Trial on Abebooks alone: four copies asking between $30-50, and the remainder commanding upwards of $150.

A good source for a Lizzie title today would be bookstores that deal in crime and true crime, such as Patterson Smith in New Jersey. Some other good places where one may find ready copies on the shelf are Cellar Stories in Providence, Rhode Island, and Murder by the Book, in Warwick, Rhode Island, both within twenty-five miles of Fall River. If, on the other hand, you are not in any hurry to find your title, eBay is an excellent source. Whether you are selective about the book’s condition or not, it is always best to ask many questions when buying on eBay. Many people who are selling books are not book dealers, and pages and an illustration or two may be missing from the volume. An incomplete book is not uncommon, and books have been delivered to me in this condition many times.

One never knows where a valuable or obscure Lizzie Borden title may turn up. Although the search is an unbelievably easy thing to do these days, I have found that the most satisfying way to discover a Lizzie title is still by chance, when you least expect it. Scanning the spines of books in the True Crime, History, Social Science, Biography, or Local History section in an out of the way, privately owned, bookstore and seeing the word Lizzie pop out at you, makes the heart beat a little faster. Such discoveries are a joy indeed and make the adventure of book hunting well worth the extra footwork.