by Michael Brimbau

First published in August/September, 2006, Volume 3, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

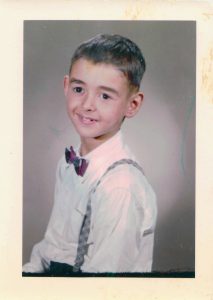

Sinking my teeth into my bottom lip, I gingerly placed one foot ahead of the other, holding my arms outstretched like a tightrope artist. I pretended I was poised a hundred feet above the Quequechan River, while the cheering crowd sighed with fright and the icy steel cable cut into my feet. Of course, there was no crowd, and the icy cable was just the cold rusted steel of the railway track that I felt through a hole in my shoe. Mom had patched it many times before. I threw down my spool of fishing string, pulled off the shoe and adjusted the Tony-the-Tiger cardboard cutout that protected the bottom of my foot and the hole in my sock. Just a couple of days ago Tony was smiling down on me from a box of cereal that sat at the morning table. With a little adjustment and a clean patch of protection, I carried on.

Sinking my teeth into my bottom lip, I gingerly placed one foot ahead of the other, holding my arms outstretched like a tightrope artist. I pretended I was poised a hundred feet above the Quequechan River, while the cheering crowd sighed with fright and the icy steel cable cut into my feet. Of course, there was no crowd, and the icy cable was just the cold rusted steel of the railway track that I felt through a hole in my shoe. Mom had patched it many times before. I threw down my spool of fishing string, pulled off the shoe and adjusted the Tony-the-Tiger cardboard cutout that protected the bottom of my foot and the hole in my sock. Just a couple of days ago Tony was smiling down on me from a box of cereal that sat at the morning table. With a little adjustment and a clean patch of protection, I carried on.

The day was clear and crisp, a chilly November day along the shore of the Quequechan River in Fall River. The three of us were playing hooky from school. Our green plaid clip-on ties hung from the back pocket of our navy blue uniform trousers. The thin strip of land supporting the railroad track we walked on continued straight down the middle of the Quequechan, between Plymouth Avenue and the Narrows near Westport. In the distance, high on a hill, on the corner of Choate and Pleasant Street, sat the four-story brick apartment building I lived in. I could just make out the outline of my bedroom window, framed in red and blue Superman curtains. A panoramic view of the Quequechan River was the first sight I awoke to every morning.

At the bottom of the hill stood our school, Espirito Santo Catholic School, the religious cornerstone and social anchor to this predominantly Portuguese Flint Neighborhood. Standing almost on the shores of the Quequechan, the Catholic mission started on Alden Street in 1910, where it proudly still stands today. The school began as the first Portuguese school in the United States, and the church was built a short two blocks away from the French church, Notre Dame. In 1927, Notre Dame would establish its own high school under the direction of Monsignor Jean A. Prevost, for which it was named. Pastor Prevost recruited French speaking Christian brothers from Canada to come and teach the French speaking population at Prevost.

By the 1950s and 60s, the Portuguese, who were still arriving in great numbers, had displaced most of the French. As Canada became prosperous, there was less reason for French Canadians to immigrate here. On the other hand, the Azores, with its third world economy, was building a new community in Fall River, a bright little American Azores right in the heart of the Flint. Just like the Island group they immigrated from, the Portuguese had little Island communities all over Fall River.

Our classmates gathered by the school’s large frame windows and enthusiastically waved to us before scattering in panic. A minute later, Sister Angelo stood there, fists on her hips, in a defiant stance. Sister motioned to us with arms and hands in an intimidating gesture of disapproval. Her penguin stance and stern appearance made me shudder with fear at what awaited when I returned to class the next day. Antone danced in place, his necktie secured like Rambo tightly around his head. The tie bounced about his face as he poked fun at Sister. “Not a very good idea Antone,” I cried. By the hasty way she quickly drew the window shades, I knew she was conferring with God at that very moment as to our punishment. There would be penance and prayer to pay, and pay dearly. But that was tomorrow, and to a preadolescent boy of ten, tomorrow was a world away—for now the freedom of this day was glorious and retribution a thing of the distant future.

Dawdling along, bamboo fishing rod in one hand and four or five catfish hanging from the other, Johnny Miranda lagged behind. He was the true fisherman among us. Antone Arruda flung a handful of oil soaked stones, picked from in-between the tracks, into the river at the frogs that sat between the reeds and grass—burping. With his neck tie still wrapped around his head and hanging over one eye, Antone was clearly the rebel in this truant group of three.

Running ahead, I was the first to notice. There it rested—the penny I had left on the train track the day before. It was flat as a potato chip, just a thin copper oval now. I was always fascinated and amused by the “stretch Lincoln” that was left behind from the massive weight of the passing freight trains. Antone snatched the compressed coin from my hand.

“Hey that’s mine,” I yelled. “I put it on the track yesterday.”

Antone ran off singing, “It’s mine now, mine now.”

Johnny shouted, “Give it back to him Antone.”

Johnny gave chase and a fight soon ensued.

The murky polluted waters of the slow migrating Quequechan surrounded us. Still, it overflowed with catfish, hornpout, and perch. Even a small bass or two would at times wander down from Watuppa Pond from the East. I cannot remember what Johnny did with the fish that day, but they were not fit to eat. In summer, the tall grass, reeds and cattails were abounding with wildlife, including turtles, frogs, snakes and birds of every description. Large snapping turtles grew to over a foot long. Their powerful jaws could mangle and crush a small boy’s fragile fingers like they were pretzel sticks. The Quequechan tributary was a true wildlife sanctuary right in the middle of the city. For the most part this went unnoticed by both the city’s blue-collar workers and politicians alike.

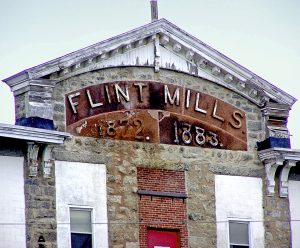

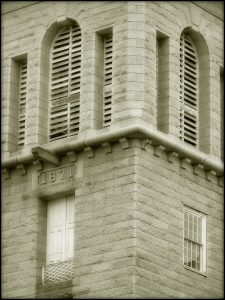

Being just children, we took our surroundings for granted. The buildings around us meant very little. History emerged in all directions. Taking up a large part of the horizon to the right was the Richard Borden Mill. The mill was built by his son Thomas, and dedicated in his father’s name in the 1870s. Years ago, while working next door to the mill, I would witness it burn to the ground. A little further on stood the Chace Mill, and to our left, the massive Durfee Union Mill Complex—the Crescent Mill closely followed that.

Not far from Crescent was the old Fall River Stadium. The stadium sat in an area between Pleasant Street and the Quequechan River, known to locals as Bigberry. Many called the field Bigberry Stadium. From the tracks where we stood, the stadium, with its lush green playing field, looked out of place amongst all the drab gray mill buildings that dominated the scenery around it. In the 1940s, Fall River had a professional baseball team named the Indians that played at the stadium. Carmen Maiocco, in his book Up the Flint, mentions that the Indians were a farm team for the Chicago White Sox. Personally, I don’t recall baseball being played at the Fall River Stadium as a child, but I do remember soccer. I remember the enormous hoopla in the Portuguese community when Portugal’s best professional team, “Benfica,” came to play. For the Portuguese community it was a chance of a lifetime. How much better could it get than to watch your favorite home team play the finest your birth country could offer? Some were left confused about which team to cheer for. Many viewed it as a mini World Cup right here in Fall River.

Like many old architectural sites around the city, years of neglect and the ravages of time claimed the old wood stadium. In the late 1960s, it was all but forgotten and a fire finished it off. In the 1970s, the stadium was removed and a park was built in its place. Today stands a beautiful amateur field in its place that is part of Britland Park.

Like many old architectural sites around the city, years of neglect and the ravages of time claimed the old wood stadium. In the late 1960s, it was all but forgotten and a fire finished it off. In the 1970s, the stadium was removed and a park was built in its place. Today stands a beautiful amateur field in its place that is part of Britland Park.

From the railroad track, the spectacle of mills along the Quequechan was endless. Still up ahead were the Pilgrim, Watuppa and Flint Mills, along with the Wampanoag and Stafford Mills.

High on a hill in the distance, towards the Northeast, the twin green baroque spires of Notre Dame Church scraped the sky. It looked apart from the land, as if suspended in the heavens. Notre Dame had always been a stunning sight of cheer and comfort, a fixed sentinel, like two proud soldiers that watched over and protected the Flint Neighborhood where I lived. It did not matter whether you attended Notre Dame or some other parish, whether you were Portuguese, French, Polish or Irish, it was there to protect all who lived near her. As a child I could not envision the skyline empty of Notre Dame. It was always there. In my unscarred innocent mind, I could not imagine otherwise. Sadly, the old French church, built 100 years ago this year, tragically burned to the ground on a sorrowful day in May of 1982. I lived close by to Notre Dame and witnessed the catastrophe first hand. I remember placing my 35mm viewfinder to my eye, not to take a picture but to conceal tears that I could not hold back. Even now as I recall, my nose stings as my eyes begin to water.

When Notre Dame burned down it also took with it a masterpiece. On its ceiling was a painting done by one of Italy’s master artists. Cremonini had painted his famous scene called “The Last Judgment.” Those who attended Mass there reported that every time they would see it, it was just like the first—breathtakingly magnificent.

In places, the water of the Quequechan was black as a pool of ink. Catfish, their stringy whiskers fanning with the water’s flow, would protrude their puffy lips at the surface as if gasping for air. As the river drifted west to Mount Hope Bay, so did dyes, chemicals and common trash. Along with these, the river carried raw sewage spewed from the mills and overflow from adjacent neighborhoods, which in many cases were discharged directly into the Quequechan.

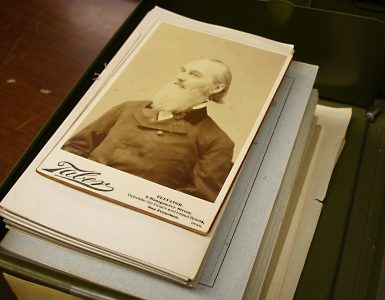

Behind the Granite Block Building on Main Street, which stood directly across from the City Hall, the Quequechan came to a head. Where the Fall River Chamber of Commerce building and Interstate 195 is today, there was a small ledge waterfall. This was the tallest fall in a group of falls that took the river from its highest level over 130 feet down to the sea. At times, the smell emitted from this downtown location was terribly offensive, as the foaming brown soup cascaded through the ruins of the old Pocasset Mill. In Lizzie Borden’s time, these falls were for the most part hidden on the property of the Pocasset Mill and the Fall River Print Works. Looking down Central and Pocasset Street from either side of the Granite Block, Lizzie would observe a string of granite mill buildings stretching for a quarter mile down to the Taunton River. It was there at the docks that the frenzy activity of loading and unloading both goods and passengers went on well into the night. Just like the migrating Quequechan River, and not looking any healthier, a steady stream of immigrants poured in from all parts of the globe. Most were carrying every possession they had in their arms and on their backs. Most had a mill job by the following day. Little did they realize that many would indirectly contribute to the excessive wealth that would eventually come to rest in Lizzie Borden’s bank account.

Back along the tracks, with no sense of time, the three of us languished. Our activities were not administered by the hands of a clock, but by the height of the sun or the glow of the streetlights along the road. In the distance behind us, we could hear a disturbing thunder and deep rumbling noise. We stood looking at one another in wonder, puzzled by what the noise could be. Johnny knelt and placed one ear to the hard rail track and listened for the train. He squinted as the icy track nipped at his cheek. At times, we could predict the train coming from long distances away. We had picked up this skill from watching one of the many westerns that dominated black and white TV in the 1950s—an old Indian trick. Suddenly, there it was again. Johnny leaped to his feet as we all turned in the direction of the sound.

“Think it’s the train?” I asked.

Johnny looked at his watch pretending to know the train schedule. He loved showing off his Mickey Mouse watch.

“Naaa, sounds like someone’s droppin’ bombs,” he said, laughing.

“Yeah, bombs,” agreed Antone. “Tat’s what it is, it’s the Germans.”

“Ahhh, go on,” said Johnny. “That’s only in the movies.”

“I thought the Germans were on our side now?” I declared, but not really sure.

“It’s the Russians comin’,” chimed Antone. “Don’t you rememba how they made us hide under the desk?”

“Ahhh, keep quiet, you don’t know what your talkin’ about,” barked Johnny.

“Look I’m a Russian plane, here comes the bombs.” Antone began to pelt us with stones. Johnny chased him up the tracks, dropping fish as he ran.

There it was again. This time the clash was accompanied by the grinding clatter of metal against metal, like the sound from a gigantic steel rattle. Johnny called me from down the track, but I could only linger and listen.

There was something ominous and evil about the noise. In the distance, a plume of smoke or dust rose into the air.

“Look!” I shouted. My tone was one of apprehension mingled with fright. I marveled at what it could possibly be.

“Com on, Mikey, it’s nothing—just some guys workin’.”

“Yea, some guys working,” I repeated.

I ran to catch up with my friends, but always looking back. Something big was happening in the distance and indeed something big it was. Down on Main Street the Laberge Wrecking Company, the people who razed Dr. Seabury Bowen’s house, were at it again. City Hall, Granite Block and all the historical buildings around them were being demolished to make a path for a new freeway that would rip a link between Providence RI, Fall River, New Bedford, and Points east to Cape Cod.

Little did we realize that our little world was about to change, and the sullied but scenic Quequechan was about to be forever transformed. Along with its tremendous wildlife, beauty and future promise, it was all to be squandered and violated, leaving a sanctuary in ruin—Interstate 195 would literally cut the city in two and would become a repulsive surgical scar of tar and galvanized steel running from east to west. Along with its tremendous aesthetic detraction, it would decimate businesses and neighborhoods with total disregard for community values and historical principles.

Driving down Interstate 195 today, with its unsightly, obscene billboards, one can only guess at what the region looked like when I was a boy. The freeway completely transformed the complexion of a quaint old New England town, robbing it of its historical identity and many beautiful and significant structures.

For one to appreciate the transformation that was inflicted on Fall River, you need only look to Lizzie Borden’s old neighborhood at 92 Second Street. I remember Second Street when it was intact. Today many of the surrounding streets have been altered or have completely vanished altogether, all in the name of progress. In the 1960s, when driving down Second Street, very little had changed since the Borden’s held residence there. Only some houses were gone—Dr. Bowen’s, Mrs. Churchill and a handful of others. In fact, the area located behind the Borden house, and stretching to the South, is intact today. Corky Row, as the neighborhood is known, encompasses Third, Fourth, Fifth, John and Spring Street, along with Wade, Morgan, Branch and several others. When I was a teenager this area was very depressed and run down. Today it has yet to recover, but perhaps that is the reason it survived. For the most part, with tenement houses and 3-Deckers built tightly together, all the streets and buildings are still standing as they did when Lizzie was alive. Sadly, most have had their Victorian trim, gingerbread, and porches chiseled off—their cedar clapboards and window adornments now bandaged in a shroud of vinyl, many are but mere boxes.

Walking down what is left of Borden and Second Street, to South Main Street and past the A. J. Borden Building on her way north to the city’s public library, the sight that would greet Lizzie would surely shake her resolve to remain in her beloved Fall River.

Writing about living in Fall River is difficult to do without touching on life in the Mills and their impact on the immigrant population. As I remember, in the 1950s and early 60s, many of Fall River’s textile mill buildings were, for the most part, occupied by garment (sewing) shops, better remembered by the sympathetic public as sweat shops. The garments made in these shops ranged from simple curtains to shirts, dresses, jackets, and finely made men’s suits. Most of the women tied to these machines were Portuguese, many first and second generations. It was not uncommon to see mother and daughter toiling side by side. The Portuguese made up 60 -75 percent of the mill population by the 1960s.

Most of my memories are of the mills bordering the Quequechan. I sat outside the Flint Mill on Alden Street waiting for my mother to end her day at Shelbourne Shirt Company. I picked at a crack in the sidewalk with a twig as an army of ants came out in a frenzy. In the distance behind the mill, I could see the train going by over the Quequechan. In the peak of summer, large fans would move around the stagnant sweltering air produced by the unrestrained sunlight that filtered through the 8-foot tall windows. Many mills did not utilize fans but instead opened all the windows, leaving the workers to pray for a cross breeze. Walking down Alden Street, I remember hearing the constant steady whining drone and buzzing of sewing machines. Growing up, I found that noise was a universal song that reverberated all over Fall River. At the end of the day, I could see all the women and girls lined up at the time clock, fanning themselves with their time cards, waiting to punch the clock.

Though sweatshop pay was much better than a maid’s wages, Bridget Sullivan had rejected such work as being too harsh. As the workers spilled out into the street, my mother rushed by me and without a pause clutched my hand and towed me along. I needed to trot to keep up with her rapid stride as she made her escape. The perspiration poured down her brow and along her face and neck. She let out a sigh and smiled to friends, puffing at their first cigarette since lunch hour, as we scurried by. I found all this behavior strange but accepted it as part of the ritual of being an adult. I was always happy to carry her small satchel that contained her piecework ticket stubs. We would count these later at the supper table and add up her earnings for the day. Instead of being paid by the hour, she was compensated by the garment and stitch. A speedy seamstress could make a commanding wage on piecework, but for obvious reasons, also, make many enemies.

Many factories in Fall River, back in the 1960s, were still dyeing and manufacturing print cloth. It was one of the city’s last surviving mill trades. Like the cotton textile trade of the past, the garment industry in Fall River, along with many other old New England mill towns, was slowly hemorrhaging and losing business to cheap labor from third world countries, such as India and Bangladesh. Fall River had strived to hold a razor thin edge on production and quality in the textile trade, but this was a battle we were about to lose. By the mid 1960s, the exodus of manufacturing jobs accelerated. In 1965, the Sagamore Mill, which stood by the shores of the Taunton River just north of the Brightman Street Bridge, stopped making cloth. This was the last real surviving textile mill in Fall River making cotton cloth. By 1975, a short ten years later, Fall River would lose upwards of 3000 mill jobs. As for the Quequechan, which was once the life-source to these textile giants lining its shore, it still flowed muddy but proud. As it surged by the once majestic granite towers, the backbones of these once proud buildings, it was to slowly witness the industry’s ultimate demise, and, eventually, its own.

We were now coming to the end of the Quequechan. Once we neared Kerr Thread Mill, the landscape became drier and less swampy. In this wooded area, with trees and open fields of brush, we chased rabbits with homemade bows, picked wild strawberries, and fled from drunks and derelicts that commonly wandered the shores of the river and pond. Some of these gentlemen were homeless, still others just looking for a peaceful place to drown their sorrows and rest weary bodies after a long hot day in the mills. A couple of these disheveled old gents pursued us along the tracks, still others held out their shaky arm and offered us a drinks from slender bottles.

“Com-UN buoys, sit down’n hafva-dwink,” they slurred.

In all cases, we would run as fast as our legs could take us.

One familiar face to everyone in the East End was an old drunk known as “Old Man Slim.” Slim was tall, lanky and looked somewhat like Abe Lincoln without a beard. He had a drawn face, deep-seated gaping eyes, and long limp slimy hair. He wore a long grimy trench coat, even in the heat of summer, and when he walked, Slim stumbled forward in a drunken zombie shuffle. It was commonplace to find Slim lying in the tall reeds by the river passed out, with a spent bottle of alcohol at his feet.

Poor Slim. I always felt a bit of compassion for him. I remember thinking he must have been a little boy like me at one time, playing down by the Quequechan. Sadly, he probably never left. As the years slipped away Fall River’s venerable textile mills and the forceful Quequechan River itself became a reflection of Slim—exhausted, tattered and forgotten.

Locals commonly knew the area behind the Kerr Mill, bordering the shores of the Watuppa pond, where it met the Quequechan, as Sandbars. The name could not be discovered on any map, but everyone knew where it was. To confuse matters further, there was little to no sand. Instead, the shore of Sandbars was spewed with large rocks and boulders. One particular boulder, everyone’s favorite swimming rock, was simply referred to as “Flat Rock.” This was the most popular swimming spot on the Watuppa in the 1950s and 60s for countless city boys. Many boys reluctantly learned to swim while being pushed off Flat Rock. Sadly, I never did. I remember bobbing up and down like a punctured plastic bottle pleading for help. Watching in amusement from Flat Rock, a group of boys laughed. At the last minute, my best friend Johnny dove in and pulled me to safety. I coughed and spit for the remainder of that day from the green water I had ingested. Some summers the South Watuppa resembled a pool of lime green Kool-Aid from a sort of algae that grew there. Understandably, Flat Rock was not one of my favorite places.

The Kerr Thread Mill, which stood directly on the banks of the South Watuppa, was an old cotton and wool thread factory started by two brothers from Scotland in 1890. By the early part of the 1900s, Kerr Thread employed 1100 workers, and, at its height, upwards of 1800 employees worked there. Sometime in the 1950s, Kerr Thread closed its doors, and over the years, the building was rented out to numerous garment and curtain factories.

In the late 1950s, part of the Kerr Mill was transformed into a discount store for cheap goods. We could think of it today as a 1950s Wal-Mart stuffed into a 19th century mill building, and just as popular. Everything a person may need was discounted there; from kitchen goods, to clothing, toys, appliances and even a cup of coffee and sandwich could be had at the Kerr Mill Bargain Center.

Bill, a friend of mine and owner of WEB Sportswear in the 1970s, would tell amusing stories about shopping at the Bargain Center. Bill had a reputation to uphold. He was the boss. The boss should be shopping downtown at Cherry and Webb or R. A. McWhirr’s, not at the Kerr. To Bill, appearance is everything—after all, he manufactured fine men’s sportswear.

“Every time I’m in the Kerr shopping, I’m dodging one of my employees,” said Bill. “Everywhere I turn, there is someone that works for me. It’s so embarrassing.” He nodded his head in frustration. “Geesh, the other day I couldn’t even get out of my car. Every time I did another one of my employees came walking out of the store.”

To Bill, image was utmost. Many have the same demeanor today when it comes to shopping at Wal-Mart or a Salvation Army thrift store. Even I must admit to scurrying in and out.

Like the proverbial broken record on Fall River History, the Kerr Thread Mill building burned to the ground in 1987 in a spectacular fire. The heat was so great that it melted the street and vinyl on houses over 200 feet away. This was one of four mammoth fires that I witnessed in Fall River. Others included the Richard Borden Mill and the Firestone Mill that was once part of the American Print Works site, just south of the Braga Bridge. All these were monster infernos that had to be witnessed to be believed.

Just southwest of the Watuppa, the Quequechan disappears into the pond. The shore here turns from swamp and marsh to rocky. Traveling further east along the train tracks, well beyond the Kerr Mill and the Narrows, you would find yourself in Westport. Just into Westport, across from where White’s of Westport is today, stood a fast food stop called the Carnival. The Carnival had the best drive-in seafood around. Countless times on the way home from a day at Lincoln Park, an amusement park in Dartmouth, between Fall River and New Bedford, we would beg our parents to pull the cord so the bus could let us out at the Carnival. They would continue home and we would linger for hours at the picnic tables, eating clam cakes and fries, looking over the pond. When we were done, we would walk the train track home, while flinging French fries at each other and watching the orange sun set behind the Kerr Mill building.

In the city’s infancy, North and South Watuppa were one pond or lake. The cleaner section to the North is where Fall River’s drinking water supply is kept today. It was there that the founder of the Fall River Bleachery, Spencer Borden, built a lavish mansion estate called Interlachen (or, land between the lakes) over one hundred years ago. The grounds were meticulously kept with sumptuous gardens and ornamental trees and shrubs that overlooked the picturesque North Watuppa. Spencer Borden was an expert on and a lover of Arabian horses, which he kept on the grounds at Interlachen. A serious horseman, Borden wrote several books on the Arabian breed of horse.

The location where the Watuppa becomes constricted, between its northern and southern portions, was naturally known as the Narrows. In the very early 1800s, a footbridge was first assembled at this location. By Lizzie’s day, a public road was in heavy use. Lizzie would have traveled this way on her treks to Marion, Fairhaven or New Bedford. Eventually the entire Narrows was filled in to accommodate the railway, Route 6 and Interstate 195, in one crossing as we see today. When I was a boy, Route 6 (most of Interstate 195), was all under water and part of South Watuppa Pond.

Continuing east just past the Kerr, you would come upon a tranquil lake scene. This was truly Fall River’s waterfront when it came to spending a peaceful day on the water. Because it was a lake, unlike the Taunton River that was Fall River’s seaport, it was calm and predictable. It’s difficult to envision today that in the 1870s a steamboat sailed the waters between the Watuppa and Quequechan. It would carry freight, passengers and excursions between points on the Quequechan on to Westport and the North Watuppa.

Although it did not boldly go where no one has gone before, the steamboat was named Enterprise. If you look very closely at the famous 1877 Messrs. Bailey & Hazen Map of Fall River, you can see the Enterprise docked near the Richard Borden Mill on the Quequechan.

In the 1950s, the railroad track ran parallel to, but separate from, the slender road that cut down the center of the Watuppa. Between this road and the railway track was a man-made enclosed body of water called Middle Pond. When I was a child, it appeared that every winter the entire Watuppa was frozen solid. It was common to see some brave, or perhaps foolish, soul driving his car on the ice and across the pond. Middle pond was usually the first place where the Watuppa would freeze. In winter, Middle Pond was crowded with families and young people ice-skating. Most of us did not own a pair of skates, but that did not stop the hoards of young boys from sliding along and knocking over those that did.

The rest of the year, the Narrows was a small boat sanctuary. On its shores were two boathouses, namely Robillard’s and Napert’s Boathouse. To us they were just “the old boathouses.” It was not until I was an adult that I discovered their names. Boats were rented here for a day of fishing, a family outing, or to the average dandy out to impress his sweetheart with his proficient rowing skills. Mr. Dupont, who lived on Walker Street just behind my mother’s home on Swindells Street, recounted how he used to race small sailboats and arrange rendezvous on the Watuppa in the 1940s.

To arrive at the Narrows from the railroad tracks, we would have to leave the tracks, cross along Portland and Catharine Streets, to the base of Pleasant Street. Pleasant Street began at the other end of town, by the side of the Academy Building on South Main Street, and like the Quequechan River, traversed the entire city to the Narrows. Today the end of Pleasant Street, along with Portland, Catherine, Estes, Porter and sections of other streets such as Prevost, Knight and County Street, were swallowed up and now lie under the freeway.

From Estes Street, the three of us continued up Pleasant Street and home. After a long day skipping school and feeling sick from eating too many wild berries, we began our long hike up Pleasant Street. By this time Johnny carried only two fish, I had lost my clip-on necktie, and Antone was sporting a black eye. Still he clutched onto his prize penny. Later he would offer to sell it to us for a dime.

Pleasant Street was a hectic world separate from the serene watery universe we had just left behind. Soon, I was walking into the living room where mom asked why I didn’t carry any books. Of course, I pretended not to hear and went directly to my room. I gazed out the window overlooking the Quequechan. The late day sun danced on the water making it sparkle like a million miniature diamonds. There I would dream.

Perhaps Johnny, Antone and I would build a raft and row it down the Quequechan, out to sea where we could discover new lands. My thoughts quickly dissolved as mom walked into the room and demanded to know what I had done with my necktie. Suddenly, a vision of Sister Angelo standing on the raft behind us, her fists clutched tightly and resting on her hips, intrusively flashed into my mind. I glared down to the church and school grounds just below the hill. The lofty steel cross atop the church’s steep gable roof gleamed, reflecting the light from the river. I thought hard about school the next day and grimaced.