by Eugene Hosey

First published in August/September, 2007, Volume 4, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Mrs. Lowndes begins with a preface that explains the rationale of her approach to the mystery. Her word is “conjecture”—inference based on incomplete evidence, or guesswork. The theory is that when literal evidence fails to solve the mystery, the key to the solution is an intelligent use of imagination that satisfies the conditions and circumstances surrounding the mystery. The author creates a plot, a cast of characters, and other relevant factors designed to make the incredible plausible. The plausibility of the author’s scenario is then submitted to the reader’s judgment.

Mrs. Lowndes begins with a preface that explains the rationale of her approach to the mystery. Her word is “conjecture”—inference based on incomplete evidence, or guesswork. The theory is that when literal evidence fails to solve the mystery, the key to the solution is an intelligent use of imagination that satisfies the conditions and circumstances surrounding the mystery. The author creates a plot, a cast of characters, and other relevant factors designed to make the incredible plausible. The plausibility of the author’s scenario is then submitted to the reader’s judgment.

The author’s most valuable contribution is the concept itself—the application of what she terms, conjecture. She starts with the premise of Lizzie’s guilt; and then without straying too far from traditional views of the known characters—she freely admits to the use of story-telling for filling in the blanks and finding escape routes from the dead-ends. Unlike so many authors who are bent on convincing the reader that they have discovered the truth when in reality they have formed subjective opinion, Mrs. Lowndes suggests the value of creative thinking in trying to solve such a frustrating murder mystery. In her preface, she makes some insightful observations, and explains exactly what she is doing:

It will be solved by surmise, by conjecture based on the evidence. This evidence is . . . so fully on record that if fact alone were enough, the mystery would have been long since penetrated.

. . .

Yet the more we know what happened, the deeper becomes the mystery . . . why Lizzie Borden killed her father and stepmother.

Into the dark secrets of motive, only surmise can penetrate. It cannot solve them, but it can offer a possible, even a probable solution.

This study in conjecture tries to relieve, by offering a credible solution, the strain that arises when the incredible has happened, and no reason can be found for it.

It is arguable, of course, but most case scholars agree that the mystery remains unsolved—unsolved whether Lizzie did it or someone else did it. Either way, it is baffling. And it is interesting that the method Lowndes describes is, in truth, the method used by later authors who wanted to be taken seriously as having discovered the truth. Victoria Lincoln and Arnold Brown (two such authors) each invented things in an effort to make a plausible story—a tricky dress change, an epileptic condition, an illegitimate son—things that may have been or may not have been, but impossible to prove. In other words, what “fact” yet introduced in order to render a solution has not been conjecture? It is interesting to read this book from 1939, compare it to one of the late 60s and then another from the early 90s—and realize that we have come no closer to the actual truth of August 4, 1892—or, if we have, we cannot be certain of it.

Mrs. Lowndes’ story is conservative, conventional, and true to the legend of Lizzie Borden as an axe murderess. The style of the writing has a dated quality that may be off-putting to some readers—that which may be fairly described as indirect and labored and formal. This is not in itself a negative, for the same observation can be made about Edgar Allan Poe and Henry James. But this is something that a reader of all the Lizzie Borden books (most of them written more recently) will notice. This literary quality is also evident in the author’s storytelling method. Rather than revealing characters through their actions, the writer “explains” them through extensive biographical exposition. This is where a static quality threatening boredom creeps into the reading experience.

Mrs. Lowndes creates four fictional characters—a pair of sisters from the past of Lizzie’s mother, Sarah Morse; and two male friends who meet Lizzie and her traveling companion in Paris. Interestingly, this idea of characters coming in pairs is thematic. Obviously, the elder spinster ladies in Boston parallel the Lizzie/Emma dynamic. And the friendship between the two men is the means through which Lizzie meets her beau. Mrs. Lowndes’ characters are incapable of successful independent thought and action. Neediness and limited ability and means prevail throughout the story—perhaps beyond the story itself as a commentary on Victorian repression.

In Paris on her 1890 trip abroad, Lizzie is conversant and friendly with a man her own age for the first time. In fact, Lizzie and Hiram Barrison are mutually naïve about relationships and romance, and there is a spark of interest between them. Hiram resides in Boston, and through the spinster ladies who knew Lizzie’s mother, Lizzie and Hiram are able to reconnect later back in America—Lizzie eventually seeing Hiram as her knight in shining armor who will take her out of the dreadful Borden house. The two meet Wednesday night of the 3rd in the barn and are seen by Abby, who threatens next morning to tell Andrew. Lizzie knows what this will mean, for she can never forget how years ago Father denied Emma’s marital choice due to the man’s poverty and brood of children that would have to be raised. After bitter words with Abby, Lizzie remembers the handleless hatchet she saw the previous night on the upper barn floor. And the rest is predictable.

The image of Lizzie pulverizing Abby’s skull with this little hatchet with a nub of a handle is ludicrous. The author introduces an explanation for how Lizzie keeps the blood off herself; this relates to a pet project of the eccentric John Morse. Dr. Bowen then plays an accomplice role in getting rid of this particular evidence. Mrs. Lowndes either makes an oversight explaining Lizzie’s murder attire for the second murder or deliberately leaves it ambiguous. There is also a curious ambiguity about the pastors who visit Lizzie in the wake of the murders. The author identifies the pastor as Reverend Jubb as he is seen from Lizzie’s point of view; and later, from Hiram Harrington’s point of view, the pastor is identified as Reverend Buck. Either both pastors are somehow present or the author fails to decide which one is there to deliver a message between Lizzie and her secret boyfriend, who is with the crowd outside the house Thursday morning.

Serious students of the Borden case who have thoroughly familiarized themselves with the documented facts and deeply contemplated the mystery are struck by an overwhelming characteristic that would seem to justify the author’s premise. What makes the conundrum so fascinating is that the evidence exists in parts or fragments that stubbornly resist cohesion. The student encounters a pattern—that credible answers to crucial questions are negated by other factors. A reasonable, logical conclusion is that a major piece of evidence is utterly missing—evidence so vital as to be necessary for understanding both motive and circumstances. Clearly, Mrs. Lowndes’ book does not rise to this challenge. Her story does not meet the standard she sets for herself in her preface—with the possible exception of supplying Lizzie Borden the axe murderess with motive. On this point, the author creates fairly complex circumstances involving all four of the principals. But the author’s rendition of the murders themselves is seriously flawed, weak, and insufficient.

This book is unusual and valuable in its argument for a method—an approach, a thought process—for solving, or at least approximating a solution, to a profoundly perplexing mystery. The creation of believable fictional characters that impact the Bordens is laudable. And it is refreshing to see the character of Abby somewhat developed instead of disparaged as fat and dumb. But the story itself is something of a letdown after reading the preface. It is worth a read, but ultimately A Study in Conjecture is a morbid Victorian romance novel ending in a heinous and ironically implausible axe murder.

Source:

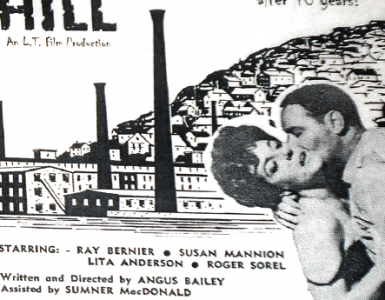

Lizzie Borden, A Study in Conjecture, Mrs. Belloc Lowndes; Longmans, Green and Co.; New York, Toronto, 1939.