by Eugene Hosey

First published in May/June, 2007, Volume 4, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

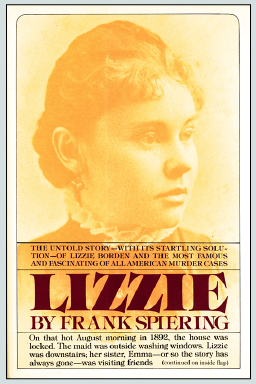

Frank Spiering names Emma Borden as the axe-wielding culprit. What is so odd is that he does it no more factually than does the Alfred Hitchcock Presents episode about the Borden sisters, a half-hour fanciful television play that portrays Emma as the guilty sister. Unlike Victoria Lincoln’s book, which is about why and how Lizzie did it—or the unsupported theory argued by Arnold Brown—Spiering’s work merely posits his notion that Emma committed the slayings while Lizzie stood by as a clean-handed accomplice who did the bulk of the suffering later.

Frank Spiering names Emma Borden as the axe-wielding culprit. What is so odd is that he does it no more factually than does the Alfred Hitchcock Presents episode about the Borden sisters, a half-hour fanciful television play that portrays Emma as the guilty sister. Unlike Victoria Lincoln’s book, which is about why and how Lizzie did it—or the unsupported theory argued by Arnold Brown—Spiering’s work merely posits his notion that Emma committed the slayings while Lizzie stood by as a clean-handed accomplice who did the bulk of the suffering later.

The author makes no effort to convince us of Emma’s guilt, and offers no theory or even argument as to her modus operandi. It appears to be merely the author’s personal opinion. Spiering indicates that Emma hated Abby even more than Lizzie hated her, and that Emma was jealous, resentful, and eager for the money. We are also reminded that the elder sister was actually in charge of the fortune. No explanation is given about the obvious logistical difficulties involved in jetting back and forth between Fairhaven and Fall River. The presentation of Emma as the killer is so weak it is hard to believe the author would deny its fictional nature. But in fact he did so in a letter to The Village Voice, refuting a damning review: “Indeed my book, which is the result of 10 years of research, points to the real killer, who was not Lizzie.” I must say that I cannot find 10 years of research in this book.

This story begins dramatically enough with Lizzie poisoning the mutton. Of course, the family members get sick but don’t die. Then Emma shows up at the front door on the morning of August 4th with an axe and a smile. This is a ludicrous scene, with Emma triple-locking the door, gesturing Lizzie to be quiet, and following her up the stairs with axe in hand for Abby. The author regards Emma’s shy, private disposition with extraordinary suspicion, which may be his only foundation for naming Emma as killer.

Spiering sticks to a straightforward, chronological style of storytelling and avoids long, pretentious sentences. Simply put, he is easy to read. He appears to understand the value of this. This is not always true of the Borden authors. His chapters are short, numbered, and named; and each includes a provocative quote from an observer, a witness, or the media. The inclusion of newspaper reports, particularly from the Fall River Globe, which established a pattern of publishing “anniversary” articles about the murders, adds unusual value to the book, revealing the paper’s dedication to taunting Lizzie in the post-murder years.

The author gives us some interesting but gossipy, unsubstantiated information about Emma, such as that she was addicted to sugar cubes and kept an axe in the latter days. That Emma hid herself, wore dark clothing as though in mourning, and would stand in the yard alone at dusk—these are interesting anecdotes that would not be inconsistent with what we do know about her reclusive life. But Spiering is not convincing in his claim to understand Emma’s heart and mind. For example, he states as fact (as if from personal knowledge) that Emma despised Nance O’Neil and feared that the relationship between Lizzie and the actress could lead to Emma’s exposure. In connection with this, the author indicates in his last section that Lizzie’s supposed lesbian relationship with O’Neil is somehow affirmed in Victoria Lincoln’s book, when in fact Lincoln’s pages reject the idea as misguided gossip. From the last chapter of A Private Disgrace: “But I doubt that she was capable of any kind of love affair. I see the Nance business only as another instance of the same nature that led Lizzie to bury her pets in the local pet cemetery around a central monument that bore the tender inscription Sleeping Awhile . . .” If only this was Spiering’s worst mistake. But there is evidence in this book of bad literary judgment – not to mention questions of professional integrity.

What a nightmare it must be for a writer to be accused of plagiarism and presented with copious examples detailed in print! Critic Walter Kendrick did so with vituperative relish in the July 10, 1984 edition of The Village Voice. The evidence against the author is overwhelming. For example, in Spiering’s chapter on the Tilden-Thurber incident, large sections of text are practically word-per-word reproductions from “The Lizzie Borden Murder Case,” 1959, by Edward Rowe Snow. What Spiering does is change a few words and phrases here and there. Snow’s “Sue away” becomes Spiering’s “Go ahead and sue.” Otherwise, the material is simply lifted, right along with the original voice of the narrative, fully intact. Of course, the proper way to have used this material would have been to offer it in summation with a reference to the source. This is but one example. Spiering also uses Victoria Lincoln’s descriptions and metaphors. Lincoln has this: “Her hands were large, but nicely formed and elegantly white. Her shoulders were rather broad, and no severity of whalebone and lacing could hide the fact that her waist was thick; so was her lower jaw.” This is Spiering’s reproduction: “Her hands were large but pale white and delicately formed. Her shoulders were broad and straight, but no amount of lacing or whalebone could hide the fact that her waist was thick.”

Due to my familiarity with The Legend of Lizzie Borden movie (1975), I detect another curious cheat. When Mrs. Churchill enters the crime scene, Spiering says: “Mrs. Churchill moved past Lizzie through the kitchen and pushed open the door of the sitting room. Stifling a gasp, she glanced at the bloody carnage that was Andrew Borden.” This is remarkably like the closing of the first scene in the movie. But it does not reflect the actual case record. From a fictional standpoint, this alone would be fine—at least, not plagiarism. But this is not all there is to it. He complicates things by creating an inaccurate scene out of this innocuous passage by tampering with what is the record. A few paragraphs later, when Dr. Bowen invites Mrs. Churchill to look at the dead Mr. Borden, Spiering has Mrs. Churchill reply in a manner indicating that she already looked in on the corpse. From Spiering: “I don’t want to see him. I saw him already . . . I don’t want to see him.” In fact, as most case students know, Mrs. Churchill actually explained that she had seen Mr. Borden alive earlier that morning and did not wish to see the carnage—not that she had already looked in the sitting room. Therefore, in essence, Spiering deliberately obscures a factual detail in order to support his fictional preference. This is oddly twisted and petty, and unavoidably irritating to read.

Because of instances of plagiarism or misrepresentation of fact, it is easy to trash this book. It was published in the early 1980s, well after Edward Radin’s book Lizzie Borden: The Untold Story (1961) where that author used both the Preliminary and Trial Transcripts to craft his tale. Perhaps the man just wanted to write an interesting book and used whatever seemed to him the most compelling material—excusing himself from actual theft by making little alterations—confusing himself about the difference between research and theft? I don’t know. The best I can say about it is that his judgment leaves something to be desired.

As a critic of Borden books, I have a problem, I confess. They are mostly not much good. Even the best ones are marred by serious errors or gaping holes of logic. But they all deserve a report. Spiering’s Lizzie is a problematic but minor entry—not as important as the Radin or the Lincoln. It is also proof that a book based on research is not necessarily more important or insightful than a brilliant piece of short fiction such as one of Angela Carter’s Gothic works. It does offer a good lesson for future writers who might unthinkingly stumble around in the gray area between their sources and their own writing.

Is there a reason to read this book? There is one high point, “Part Two: The Trial.” It is a good summation of the interactions of the Prosecution and Defense. The impact of several important decisions made by the justices is clearly explained. The reader is not bogged down in tiresome Q-and-A. The author nicely weaves into the proceedings the perspective of a journalist of the time and present at the trial, Joe Howard. This man’s existence is verified in the Rebello book, and if Spiering is accurate about his role, the journalist provides some of the most colorful, illuminating descriptions I have read. But the blight of plagiarism and deliberate fact-tampering calls everything into question, which is unfortunate because the book is not badly constructed or poorly written.

Works Consulted:

Kendrick, Walter. “Hatchet Work or Hatchet Job, Lizzie Borden: The Case That Will Not Close.” Village Voice: July 10, 1984.

Lincoln, Victoria. A Private Disgrace: Lizzie Borden by Daylight. NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1967.

Snow, Edward Rowe. “The Lizzie Borden Murder Case.” Piracy, Mutiny and Murder. NY: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1959.

Spiering, Frank. Lizzie. NY: Pinnacle Books, 1984.

Spiering, Frank. “Walter Kendrick Took an Ax.” The Village Voice: July 25, 1984.