by Eugene Hosey

First published in February/March, 2007, Volume 4, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

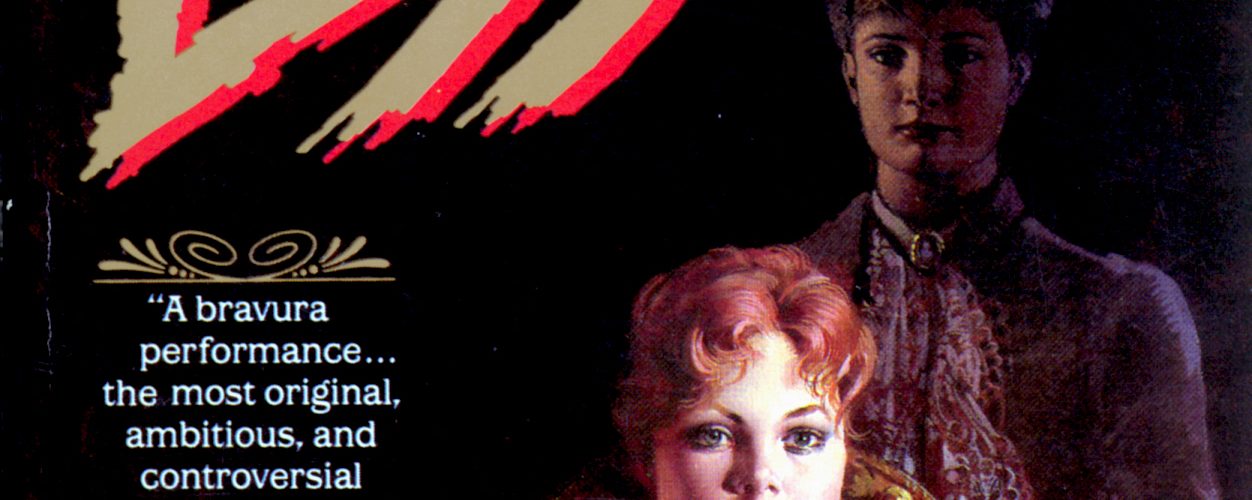

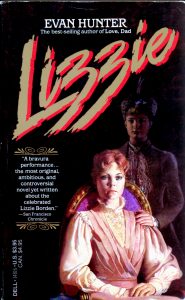

Evan Hunter’s Lizzie, copyrighted 1984, is not the best Lizzie book but it is not the worst one either. Superior to the ludicrously dreadful story by Engstrom, Hunter’s story lacks the intense narrative drive of Lincoln’s legend-affirming book. It is not based on conspiratorial convolutions that overwhelm the radical theory of Arnold Brown. Lizzie is a curious, at times entertaining book that the author defines as a work of fiction which includes a respect for the actual crime record.

The book has three distinct components—a purely fictional account of Lizzie’s 1890 trip abroad, the 1893 trial in New Bedford, and a solution to the mystery of the murders. These components represent different layers or aspects of interest—Lizzie herself, personally; what came to light during the trial; and a fascinating hypothesis of how the murders occurred and by whom. The chapters consistently alternate between the days in the courtroom and the story of how Lizzie discovered her sexuality in Europe. The two stories run independently of each other and could actually be extracted to form two shorter books. Apparently, the purpose of the shift is to gradually inform the reader of Lizzie’s secret as the trial unfolds. This secret will explain the murder of Abby.

The book has three distinct components—a purely fictional account of Lizzie’s 1890 trip abroad, the 1893 trial in New Bedford, and a solution to the mystery of the murders. These components represent different layers or aspects of interest—Lizzie herself, personally; what came to light during the trial; and a fascinating hypothesis of how the murders occurred and by whom. The chapters consistently alternate between the days in the courtroom and the story of how Lizzie discovered her sexuality in Europe. The two stories run independently of each other and could actually be extracted to form two shorter books. Apparently, the purpose of the shift is to gradually inform the reader of Lizzie’s secret as the trial unfolds. This secret will explain the murder of Abby.

Like Porter in his 1893 book, Hunter eliminates much of the question-and-answer form of the trial document in favor of presenting testimonies as uninterrupted monologues. The obvious benefit in choosing to do so makes this material a less tedious reading experience, condensing in long paragraphs a Q-and-A transcription that would necessitate significantly greater page length. Arranging testimony into narrative form also enables the author to present a chronological order of events in one place and a compilation of topical evidence—the condition of the bodies, the distribution of blood—in another. Any reader—seasoned or uninformed—may enjoy reading this more eloquent flow of the trial evidence. But the reader should understand—as Hunter himself explains in an Afterword—that whereas the author has respected the testimony and has not knowingly distorted it, he has nevertheless used only what he wanted; and he has abbreviated and edited his choices. In other words, the courtroom chapters are not acceptable alternatives to the actual documentation of Lizzie’s Inquest or the Trial.

Unlike Lincoln and Brown, Hunter is smart enough to classify his work as fictional, although it is possible—judging from his detailed account of the crimes—that he would appreciate a serious consideration of his theory. He makes a competent effort to account for the most minute, puzzling questions, to “cover all the bases.” His denouement is certainly interesting, partially successful—but with definite weaknesses.

While abroad in 1890, Lizzie meets an aristocratic, pretentious lady named Alison whose candor and hedonism initially shock Lizzie. But gradually Alison’s interest in Lizzie is returned, and the two enjoy a lesbian relationship. This is presented as Lizzie’s journey of self-discovery, which includes a traumatic break with her puritanical upbringing together with a profoundly exciting liberation. This relationship ends when Lizzie returns to Fall River, and Lizzie feels grief, longing, and desperation that lead her to impulses and acts that Alison actually warned her against. Lizzie cannot readjust to the same life in her father’s house. Her view of Bridget takes on a new dimension, and Hunter creates a credible basis for a collusion between Lizzie and Bridget.

Several points should be made about the writing style Hunter uses in his story of Alison and Lizzie. It is not technically bad, but he opts for the stereotypical characterizations and florid, mannered prose of the “Victorian” romance novel with sexually explicit touches. He treats the contrast between the worldly seductress and the repressed spinster as an elaborate sexual tease. As the sex approaches and happens, one senses Hunter’s interest in lesbian erotica. It is here that he seems to luxuriate somewhat as a writer, taking his time and elaborating in description. One cannot help but wonder if this subject interested him as a writer more than anything else.

Hunter plays it safe with his portrayal of Lizzie as she reacts to rich European society and its cliched ornaments such as Alison and her brother. Lizzie is naïve, sensitive, and easily influenced. Alison simply overwhelms her. But is she an interesting character is her own right? When all is said and done, it is hard to be sure if Lizzie has been victimized by her friend or if she has become a version of Alison herself.

Any detailed solution to the murders demands a critique based on documented fact, plausibility, and probability. Because so many readers are looking for this, even if the author states unequivocally that the story is fictional, this critique is unavoidable. For those who may wish to experience the ending without commentary, please note that spoilers are ahead.

Hunter does give an inventive yet reasonably plausible explanation for the murders—one for which he tells a long story to establish. His theory addresses some of the most vexing questions such as why Abby was killed exactly where and when, the substance of Bridget’s collusion and what became of the axe, and why Lizzie tried to buy Prussic acid. It even accounts for the pounding noise heard the night before and the relatively innocuous appearances of men about the house on the morning of the murders; Lubinsky’s citing of Lizzie is verified. At least to some degree, Hunter succeeds in writing a psychological tour-de-force, where unplanned murders happen for intensely personal reasons involving a series of indiscretions and hysterical, explosive reactions—a lesbian incident between Lizzie and Bridget at the root of the tragedy.

A truly weak part in the theory is the candlestick as a murder weapon. No matter how heavy or how sharp the edges of the square base of a candlestick, it is not designed to be such an effective cutting weapon as evidenced on Abby’s battered skull. Further, it is an implausible narrative stretch for Andrew to notice the candlestick downstairs, recognizing where it belongs, and his subsequent insistence on taking it upstairs himself to discover Abby’s body.

There is also a problem in the explanation of the ubiquitous mystery of the role played by Lizzie’s dress—the exact problem of it far from new. For the first murder, Lizzie is wearing nothing—a convenient circumstance. But then he has her put on a dress never seen or mentioned by anyone before Andrew gets home. This one she wears for his murder and burns immediately afterwards. When Bridget points out that buttons may be discovered in the ashes, Lizzie tells her that in light of this, she will make certain to burn another dress later in the presence of a witness. This is certainly a weak explanation of the dress-burning as witnessed by Alice Russell.

Then Hunter duplicates the problem Victoria Lincoln gave us in having Lizzie put on the bengaline silk to be seen by witnesses, which is in fact the dress Lizzie gave the police. This explanation is extremely faulty, because witnesses (Mrs. Churchill, in particular) who retained memory about Lizzie’s fabric in the aftermath of the murders could not remember this dress Lizzie claimed to have worn. Where memory among witnesses did serve, the recollection was of a different dress—not this one displayed in court. (Some readers might wish to compare the complete testimony on this subject with what the author has chosen to include on the subject in his courtroom section.) This is a failure of cleverness on the part of the author, and one must wonder about Hunter’s thought process concerning it. Did he simply “lift” this from Victoria Lincoln, knowing its problematical aspect in regard to case facts, choosing it as a matter of convenience? We can add to this subject as well the interesting fact that Hunter (unlike Lincoln) renders the infamous Bedford cord as an “innocent bystander” in the actual commission of the murders. There are still other minor weaknesses in Hunter’s account of the murders (Abby’s reason for returning to the house, for example) as well as some clever touches (how the back door got left unlatched so that Abby could re-enter unheard).

In the final analysis, Hunter’s Lizzie is a novel based on the mystery of the Borden murders. It is not a factual solution. Nor does the author make the claim. The author’s first statement in his Afterword is, “Although this is a work of fiction, much of it is rooted firmly in fact.” But the book is a difficult mixture of fact and fiction—of parts believable and unbelievable. It reads as if the writer were secretly trying for a legitimate theory, while simultaneously avoiding serious criticism for it by falling back on the conditions of fiction. Or perhaps the author is deliberately playing this sort of game—teasing the serious students of the case, while entertaining the masses with a macabre story of parricide emboldened with Victorian lesbianism. This being said, then what is this book as pure fiction? It seems to occupy a place of mediocrity. The dual story line has an artificial, superimposed feel; and the last chapter is flawed by some far-fetched twists and turns that come across as a conflict between creative invention and accountability to a factual record.