by Eugene Hosey

First published in May/June, 2006, Volume 3, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

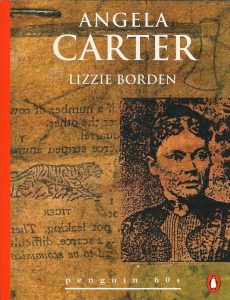

Angela Carter’s version of the Lizzie Borden story is an American Gothic tale about a household rife with the awful conditions for parricide in a particular time, at a particular place—Fall River, summer 1892. The house of the crime presents a mask of respectability to the world, as symbolized by the pretty script on the brass plate by the exterior of the front door. Carter’s perspective is interesting in that she is an English writer making a study of the descendants of the Puritans, who have historical ties to a branch of her own countrymen. One definitely gets the impression that she at least believes she knows who these people are, and her assessment of the stuff they are made of is unrelentingly hard. Her conception is heavily invested in the elements of setting: a ruthless factory of a world, broiling in a white furnace of a sun, unnatural and masochistic in both public and private quarters. In fact, Carter’s original title (before the eventual change to “The Fall River Axe Murders”) was “Mise-en-scène for Parricide.”

Angela Carter’s version of the Lizzie Borden story is an American Gothic tale about a household rife with the awful conditions for parricide in a particular time, at a particular place—Fall River, summer 1892. The house of the crime presents a mask of respectability to the world, as symbolized by the pretty script on the brass plate by the exterior of the front door. Carter’s perspective is interesting in that she is an English writer making a study of the descendants of the Puritans, who have historical ties to a branch of her own countrymen. One definitely gets the impression that she at least believes she knows who these people are, and her assessment of the stuff they are made of is unrelentingly hard. Her conception is heavily invested in the elements of setting: a ruthless factory of a world, broiling in a white furnace of a sun, unnatural and masochistic in both public and private quarters. In fact, Carter’s original title (before the eventual change to “The Fall River Axe Murders”) was “Mise-en-scène for Parricide.”

Carter’s story is a literary work—as opposed to routine, mediocre or junk fiction—and therefore a treasure-filled composition that is as much a joy to analyze as it is to read. The qualitative adjective, “literary,” is not from snobbishness but from an appreciation of what we usually call “voice” and “form.”

Carter’s voice is that of the voyeuristic, unidentified observer who takes us inside the Borden house in order to show us the stage that fate has arranged for what the author aptly describes as the “domestic apocalypse.” She is respectful about the facts of the case, yet the superior commentator’s voice breaks through boldly with an explanation when she decides to dispense with Morse: “The other old man is some kind of kin of Borden’s. He doesn’t belong here; he is visiting, passing through, he is a chance bystander, he is irrelevant. Write him out of the script.”

“The Fall River Axe Murders” takes place inside a single moment in terms of real time and ends where it starts. This is accomplished by forming the narrative based on the circle or vortex—as opposed to the traditional linear narrative that finds the beginning, middle, and end of a story. Within this single moment of time are elaborate descriptions, character development, and strange anecdotes that either advance speculatively or flash backward. We know early on that Lizzie Borden will kill her parents, and we accept the inevitability of this. By freezing what would in reality be the fleeting period of time before the first awakening of the first member of the household, Carter stages and then dilates upon the guts, heart, and soul of the terminal misery afflicting the inmates of 92 Second Street, and leaves us at the brink of the nightmarish climax. To Angela Carter’s credit as a literary artist, it is not necessary for the reader to know the historical facts of the Fall River tragedy in order to appreciate the powerful tale. Carter develops the dysfunctional (or non-functional) family into an epic of gothic horror, where the characters are actually the externalized characterizations of psychological and moral sickness. The status quo of the Borden house cannot stand forever- it is precariously balanced on abnormal conditions that must ultimately cause implosion.

Carter has a penetrating, intuitive grasp of the elements that make this legendary murder case so fascinating. Her analogies and metaphors are brilliant. Andrew and Abby Borden are Jack Spratt and his fat wife; further, Andrew’s bony structure is the physical manifestation of his parsimony, while Abby’s fat represents gluttony—a desire to consume as much as possible in a futile effort to fill the bottomless hole of a meaningless life. Neither spouse knows pleasure. They are not merely a grotesque couple. Their marriage is a hideous irony. As Carter portrays them: “Here they lie in bed together, living embodiments of two of the Seven Deadly Sins, but he knows his avarice is no offense because he never spends any money and she knows she is not greedy because the grub she shovels down gives her dyspepsia.” Carter is commenting on a moral truth here. The lover of money knows not how to use it, and the glutton is no connoisseur of fine taste.

The author is also judging what she sees and understands as the New Englanders’ inheritance of a Puritanical tendency—which is, in essence, the eschewing of pleasure and the worship of misery. Perhaps Carter pushes this particular envelope a bit too far when she writes of Andrew: “He is at peace with his god for he has used his talents as the Good Book says he should.” But this is a minor criticism, in the sense that we do not lose touch with the author’s point about the dangers of severely limited or aberrant moral judgment. Nevertheless, Carter’s own personal prejudice against religious instruction or belief surfaces here in a way that it really should not. Her exact wording seems to be a sort of Freudian slip—for, in fact, the “Good Book,” as she calls it, does not teach parsimony and cruelty. Carter would have been wiser to say that Andrew had never bothered to read the Bible and believed a fraudulent version of it based on perversions that suited his selfish purposes. We may believe this is what she means, but this is not what she actually says—and brilliant writers who are worthy of analysis automatically raise the critical bar.

The author’s portrait of Andrew is the most monstrous of the house and the most successful, which is as it should be since he is the ruler of this diseased domicile. His favorite sport is foreclosing on the poor, creating destitution, either for the sake of making a more profitable leasing arrangement or just for the thrill of exercising power. Carter’s realization of Mr. Borden, physically speaking, is remarkable in its factual accuracy and reflects the morally grotesque embodiment she aims for. Describing that grim face with its white strip of a beard, she says: “He looks as if he’d gnawed his lips off.” Most of us know that photograph so well it is hard not to chuckle approvingly at how succinctly she says exactly what there is to say about it. Her description of his figure as it would be seen walking down the street upholds Mrs. Churchill’s insistence on the adjective “straight” in describing Mr. Borden’s appearance in her testimony. Carter sees him as someone not quite human, but more like a personage manufactured by some diabolical factory. The author never delves more deeply into the grotesque than when she invents this: “His spine is like an iron rod, forged, not born, impossible to imagine that spine of Old Borden’s curled up in the womb in the big C of the foetus; he walks as if his legs had joints at neither knee nor ankles so that his feet hit the trembling earth like a bailiff pounding a door.” As grim as the imagery gets, Carter’s sardonic wit is always close at hand. She compares Andrew’s dignity to that of a hearse; and mentions that he would like to charge the cockroaches in his kitchen for rent. She even treats us to the intimate detail that the only rigid thing he ever offered his wife in bed was his unnaturally formed backbone.

Lizzie Borden, the protagonist in the crimes about to happen, is more an anomalous creature than her father. It is impossible to truly know her, since she totters on the brink of insanity. She is a pathetic creature, given to dissociating, strange trances, and weirdly imaginative thoughts. Unfortunately for the whole family, the impenetrable mysteries of Lizzie Borden are deadly. Carter devotes two paragraphs to a study of Lizzie’s face as we see it in photographs—unremarkable on the one hand, and yet ominously shadowed. She has “eyes that belong to a person who does not listen to you.” Her face “secretes mystery.” Her hostility toward Abby seems to be rooted in fear of her stepmother’s gluttony—the fear that Abby will eventually devour everything Lizzie cares about takes root in her unstable mind. The slaughtered pigeons that Abby wanted to eat deeply disturb her, and thus it is that Lizzie decides to go down cellar to examine the cleaned hatchet Andrew used on the birds.

And so the fateful morning of August 4th, 1892 dawns in Fall River, and its citizenry is about to begin their routine. As the clocks, alarms, and factory whistles begin to sound just as they do every day, nothing unusual will happen with the shocking exception that the lid on the Borden pressure cooker will finally blow.

Angela Carter’s style is strongly visual, and her emphasis on mise-en-scène suggests the theatrical production. “The Fall River Axe Murders” has been adapted to at least one play in recent years, The Fall River Axe Murders: Literature in Performance, in San Francisco, August 2003. There is also provocative cinematic potential in Carter’s work. Carter herself wrote two screenplays, The Company of Wolves (1984) and The Magic Toyshop (1987). The Company of Wolves was based on an amalgam of several of her wolf stories, resulting in an atmospheric, fantasy/horror movie.

Any lover of cinema, which is perhaps the medium that is closest to what we may call the dream world, can imagine stunning possibilities in reading both some of her wild analogies and her quietly subtle visuals. The image of Abby as a fat monster at the center of a spider web, for example—how might a talented filmmaker with a love for surrealism work this out on screen? In another instance, one can envision a beautiful way for the camera to move from the backyard and into the house: As the sun rises, the camera focuses on the pear trees—the leaves and the fruit—and through a gap in the branches, we spot Bridget’s attic window. With a slow zoom, the camera comes to rest on that exterior window, where it dissolves into the interior of Bridget’s window, revealing the blinds through which the shadows of pears and leaves flutter as Carter describes: “On bright rectangles of paper blinds move the beautiful shadows of the pear trees.” Our imaginary camera is then free to roam the sleeping house like a supernatural spy, which is the setting Carter evokes.

“The Fall River Axe Murders” is a strong work of fiction that bears the integrity of truth. Carter is not interested in formulating a pretentious theory about how the murders happened on that infamous day. Rather, she invests her literary skills in the truth of how the Borden tragedy lends itself to the Gothic tradition. All real writers find truth, regardless of the fact that defining truth is a never-ending argument. The grotesqueries of the setting are rooted in realistic factors of the 1892 mill town. We can smell the animal dung and urine of the street wafting through the windows, as well as the sickening odor of sweaty sheets, unwashed garments reused, and slop pails or vomit pails. We sense the cheerless spirit of the doomed house, the claustrophobia of locked rooms, and the feverish heat that will finally drive the inmates from their beds into the harsh glare of another mean day, where apocalypse awaits.

NOTE: For this review, I have used the story as it appears in Burning Your Boats (1997), which includes a reprint of the collection Black Venus (1985). A modestly edited version of the story that does not significantly affect the narrative appeared in the collection, Saints and Strangers (1986). The story was originally published in 1981 in The London Review of Books, entitled, “Mise-en-scène for Parricide.” The quotations used in this review all come from Carter’s story—with the exception of the reference to Mrs. Churchill’s statement, and as quotes are used to call attention to the usage of a particular word.