by Eugene Hosey

First published in February/March, 2006, Volume 3, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

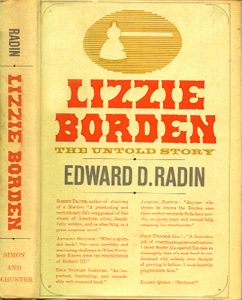

Thirty years after O. J. Simpson is dead, when his solidified reputation as an acquitted murderer has fossilized, someone will probably write a book about the untold story of his innocence. This hypothetical book is sure to get some hostile reactions, as did Edward Radin’s book about Lizzie Borden in 1961.

If Radin accomplished but one thing, he demonstrated that the literal facts of the case did not necessarily nail Lizzie Borden as an axe murderer. In fact, there was at least one other person at the scene of the crimes, and with the same opportunity and means that was available to Lizzie Borden.

Lizzie Borden, The Untold Story was a commercial success, making the New York Times bestseller list in 1961. It was widely reviewed in major publications and was critically controversial. A review in the New York Times, May 28th, 1961, concluded with a recommendation: “For sheer gripping entertainment, human understanding and powerful reasoning, his book is a brilliant tour de force.” On the other hand, it received some stunning vitriol. In the August 1961 issue of Esquire, Dorothy Parker treated it with a derision that denied it a single iota of merit. It was not just Radin’s view of Lizzie or Bridget Sullivan that particularly offended certain professionals. The real stinger was Radin’s chapter on Edmund Pearson, which was an accusation of fraudulent analysis. Pearson was a highly respected writer and criminologist. He had written extensively about the Borden case, absolutely convinced that Lizzie was an acquitted axe-murderer. His work had, in effect, crowned Lizzie Borden’s guilty reputation with scholarly credence. Moreover, by 1961, Pearson was no longer around to defend himself. A 1963 volume of works by Pearson included a postscript by Gerald Gross entitled, “The Pearson-Radin Controversy Over the Guilt of Lizzie Borden.” This writer’s comments are revealing about the mindset Radin was up against at the time, as well as the influence Radin could paradoxically enjoy. From the Gross article:

Lizzie Borden, The Untold Story was a commercial success, making the New York Times bestseller list in 1961. It was widely reviewed in major publications and was critically controversial. A review in the New York Times, May 28th, 1961, concluded with a recommendation: “For sheer gripping entertainment, human understanding and powerful reasoning, his book is a brilliant tour de force.” On the other hand, it received some stunning vitriol. In the August 1961 issue of Esquire, Dorothy Parker treated it with a derision that denied it a single iota of merit. It was not just Radin’s view of Lizzie or Bridget Sullivan that particularly offended certain professionals. The real stinger was Radin’s chapter on Edmund Pearson, which was an accusation of fraudulent analysis. Pearson was a highly respected writer and criminologist. He had written extensively about the Borden case, absolutely convinced that Lizzie was an acquitted axe-murderer. His work had, in effect, crowned Lizzie Borden’s guilty reputation with scholarly credence. Moreover, by 1961, Pearson was no longer around to defend himself. A 1963 volume of works by Pearson included a postscript by Gerald Gross entitled, “The Pearson-Radin Controversy Over the Guilt of Lizzie Borden.” This writer’s comments are revealing about the mindset Radin was up against at the time, as well as the influence Radin could paradoxically enjoy. From the Gross article:

For thirty-seven years, ever since he published The Borden Case in 1924, Edmund Pearson went unchallenged as the final authority on that most incredible of American murders — the axing to death of Mr. and Mrs. Andrew Borden in their house in Fall River, Massachusetts, on a brutally hot morning in August, 1892. Their daughter Lizzie was tried for the crime and was acquitted. But Edmund Pearson believed her to be guilty, and so did the reading public he influenced (274).

. . . .

My own feelings are of course apparent: I feel that Radin maligned Pearson’s reputation with unnecessary cruelty. This essay, then, is my own attempt to restore the luster to Mr. Pearson’s reputation (275).

A negative assessment of a star is a bitter pill for fans to swallow. After all, the criticism reflects on the supporters as well — without whom the esteemed authority could not have attained his status. Interestingly, a reader of this essay by Gerald Gross will discover that his defense of Pearson is actually an introduction to his own hypothesis of a Lizzie/Bridget collusion.

Presently, nothing hinders us from appreciating the contributions of both Pearson and Radin. What may for the most part be considered established fact at one point in time changes and becomes an opinion in another. A controversy in 1961 is a question of perspective and focus now — when we may wisely presume that someone had to take the heat for finding Lizzie Borden innocent.

The Untold Story is not a flowing narrative, advancing chapter by chapter a sequence of events that resolves at the end. Rather, thematic or topical chapters that defend Lizzie in various ways structure the book. Interestingly, each chapter could work as a standalone article with little or no revision. Radin’s first chapter includes an extremely well written, economical rendition of The Legend that conveys the uncanny brutality and nerve of the suspected parricidal axe murderess.

So, what of Radin’s controversial, “The Case Against Pearson?” It is an oddity in the Borden literature. Whereas Radin does argue in detail against Pearson, his accusations become much-ado-about-nothing under scrutiny. The bulk of this diatribe is petty and misleading, with Radin making himself guilty of the obfuscation and omissions he claims to have discovered in Pearson. The official case records are readily available, and so the reader can easily sort through this material at will. But to observe three of the major points upon which Radin takes Pearson to task:

1) The Dress. Radin complained that Pearson described the dress that Lizzie handed over as the murder-morning garment as pure silk as opposed to part silk. This seems to be an attempt to kick the issue aside or to misrepresent the real issue at hand regarding the dress. There was a visible difference between silk and cotton dress goods. At the trial, Mrs. Churchill was certain Lizzie had worn a cotton dress murder morning. And Alice Russell, when shown the dress skirt on exhibit, said of it: “Well, I don’t know what it is. It is silk, but I don’t know what kind” (T 415).

2) Eli Bence. Radin asserts that Bence identified Lizzie solely by the sound of her voice, and that Pearson had deliberately concealed this fact by not printing all or more of Bence’s Inquest testimony. This is strange. Did Radin not read the Inquest himself? Or did he presume the reading public would never have access to it? When Bence was asked if he had then known the identity of the woman who tried to purchase prussic acid the day before the murders, he answered: “I knew her as a Miss Borden; I have known her for sometime as a Miss Borden, but not as Andrew J. Borden’s daughter until that morning. One of the gentlemen who was sitting there, when she turned around and went out, he says ‘that is Andrew J. Borden’s daughter.’ I looked at her a second time then more closely than when I was talking to her. I should say it was Miss Borden” (I 160). Bence then stated that he had not seen her in the store before, but had seen her on the street. Bence further explained that a lady entered his store the evening after the murders and told him that she understood they were suspecting the daughter. He continued that on the night of August 4th, he went to the house with Officers Doherty and Harrington. The following detailed exchange from Bence’s testimony fleshes out the remarkable details of which Radin chose to oversimplify as an incident of a mere voice-recognition:

Q. Did you there see Lizzie Borden?

A. I did, yes sir.

Q. Where was she when you saw her?

A. In the kitchen, talking with Officer Harrington.

Q. Did you recognize her as the one that you had had the talk with the night before?

NOTE: The choice of the word, “night” in the question is apparently a simple mistake, since the time of Lizzie’s alleged visit to the drug store was never in question. Bence estimated Lizzie came in August 3rd before his dinnertime, between ten and half past eleven (I 160).

A. I did, yes sir.

Q. Positively?

A. I dont think I could be mistaken.

Q. How did you judge?

A. I judged both from seeing her before on the street, and also by a peculiar expression around the eyes, which I noticed at the time, and noticed then.

Q. Did you hear her talk?

A. I did.

Q. Did you identify the voice?

A. I did.

Q. You went in for the purpose of seeing if she was the one?

A. Yes Sir.

Q. Did you speak to her that evening in there?

A. I did not (I 161-162).

It is a generally accepted view that eyewitness reports are by no means reliable. However, the report given by Bence is remarkable in its extent and specificity.

3) Lizzie’s Trip to Marion. Radin accuses Pearson of using a footnote deceptively in order to make it appear that Lizzie was lying to Alice Russell Wednesday night about her decision to go to Marion. The problem here is that neither author clearly sources their quotations. Pearson edits what appears to be from Alice Russell’s trial testimony. Radin’s quote (p. 179, Dell paperback) is his claim of what Lizzie had told Miss Russell: “I am going to take your advice and go to Marion on Monday.” Radin says Lizzie said this. From Alice Russell’s trial testimony: “I think when she came in she said, ‘I have taken your advice, and I have written to Marion that I will come.’ I don’t know what came in between, I don’t know as this followed that, but I said, ‘I am glad you are going,’ as I had urged her to go before” (T 375). At the inquest, Lizzie was asked why she did not go to Marion with the party that went. Her answer: “Because they went sooner than I could, and I was going Monday” (I 56). Apparently, Radin attaches significant weight to whether Lizzie was specific with Miss Russell about planning to go on Monday—but Radin’s quote attributed to Lizzie would appear to be invention on his part.

These three samples characterize the tediousness of Radin’s quarrel with Pearson. Radin’s objections about Pearson’s book do not clarify anything. Radin’s rationale is frequently unclear. Why did Radin strain a gnat and swallow a camel? He must have believed a refutation of Pearson was necessary. A real lesson to be learned from this concerns the importance of the use of primary sources when making an argument and the pitfalls of paraphrasing. It should also be said that we expect authors to be challenged and criticized.

In the historical context, The Untold Story audaciously prodded a world convinced of Lizzie’s guilt. Nevertheless, we would be remiss in the most objective world if we did not suspect Bridget Sullivan. In his chapter, “The Big Question,” Radin puts prosaic details to constructive work in his timetable for August 4th that compares the testimonies of Bridget and Lizzie. This is a substantive contribution, much appreciated, and still used today. Radin deserves special credit for his detailed investigation of Lizzie’s so-called confession: a note admitting the act of August 4th, 1892 and apparently signed, Lizbeth A. Borden. This was a product of the Tilden-Thurber controversy of 1897, alleging Lizzie’s theft of two paintings. The subject is examined in meticulous detail in an article by Sherry Chapman is the August/September 2005 issue of The Hatchet. Radin presents a strong case that this signature is a forgery. Radin’s interviews with Fall River natives would seem to be of high value, but they totally fail to reveal her as an individual to any believable degree. Ironically, a quote from Pearson’s, The Trial of Lizzie Borden, couldn’t be more appropriate: “I have talked with at least two persons who knew Miss Borden intimately, and for many years, as well as with others who had some acquaintance with her. No one had any explanation of her character, or pretended to knowledge of her inner life.”

Works Cited

Burt, Frank H. The Trial of Lizzie A. Borden. Upon an indictment charging her with the murders of Abby Durfee Borden and Andrew Jackson Bordon. Before the Superior Court for the County of Bristol. Presiding, C.J. Mason, J.J. Blodgett, and J.J. Dewey. Official stenographic report by Frank H. Burt. New Bedford, MA, 1893; Orlando: PearTree Press, 2004.

de la Torre, Lillian. “Who Gave the 40 Whacks?” New York Times (28 May 1961): 6.

Gross, Gerald. “The Pearson-Radin Controversy Over the Guilt of Lizzie Borden.” Masterpieces of Murder: An Edmund Lester Pearson True Crime Reader. Ed. Gerald Gross. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1963, pp. 274-285.

Inquest Upon the Deaths of Andrew J. and Abby D. Borden, August 9 – 11, 1892, Volume I and II. Fall River, MA: Fall River Historical Society; Orlando: PearTree Press, 2004.

Parker, Dorothy. Esquire (August 1961): 16, 20.

Pearson, Edmund. The Trial of Lizzie Borden. NY: Doubleday, Doran & Company, 1937.

Radin, Edward D. Lizzie Borden, The Untold Story. NY: Dell Publishing Company, 1962.