by Eugene Hosey

First published in January/February, 2008, Volume 5, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

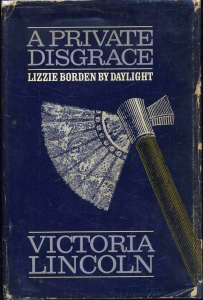

A Private Disgrace: Lizzie Borden by Daylight has been one of the most influential books in the Borden literature. For the dedicated student it is required reading. Many of Victoria Lincoln’s ideas have become commonly held (though factually unsubstantiated) beliefs among readers. That for one reason or another Andrew returned home early the morning of the murders, that Lizzie’s mention of a fleabite was a Victorian euphemism for menstruation—these appear to have originated with Lincoln. There are other misleading, unverifiable claims and bright inventions and embellishments. These are vexing negatives in light of the author’s insistence that her book is the truth. On the other hand, popular suppositions and theories about a case so enduring and deeply mysterious as this one become ubiquitous, and acquire an apocryphal importance.

A Private Disgrace: Lizzie Borden by Daylight has been one of the most influential books in the Borden literature. For the dedicated student it is required reading. Many of Victoria Lincoln’s ideas have become commonly held (though factually unsubstantiated) beliefs among readers. That for one reason or another Andrew returned home early the morning of the murders, that Lizzie’s mention of a fleabite was a Victorian euphemism for menstruation—these appear to have originated with Lincoln. There are other misleading, unverifiable claims and bright inventions and embellishments. These are vexing negatives in light of the author’s insistence that her book is the truth. On the other hand, popular suppositions and theories about a case so enduring and deeply mysterious as this one become ubiquitous, and acquire an apocryphal importance.

This was the first Lizzie Borden book I read, and at the time I accepted it as fact and solution. Later when I became educated about the case, I denounced it as a fraud and critically ripped it to pieces. After re-reading it several times, I now appreciate it as an inspired dramatization of those insidious murders. A Private Disgrace is a book to enjoy or even treasure, once the reader comes to terms with what it is and what it is not.

A Private Disgrace is not the truth. Ms. Lincoln does not, as she enthusiastically contends, solve the case. Her solution, posited as nonfiction and biographical, based on fact and knowledge, is actually a specious construction. Lincoln theorizes that Lizzie did it, as legend would have it, and many of the author’s murderous ideas, speculative and unverifiable as they are, are not necessarily impossible. But it is Victoria Lincoln’s dress theory—Lizzie’s principal ruse that according to the author saved Lizzie Borden—that clearly falls apart under scrutiny, unless one can justify omission of some of the most important testimony given. Lincoln claims in misleading fashion that no two witnesses could agree on what Lizzie wore the bloody Thursday morning—that therefore she was able to fool witnesses about what they saw. An examination of the trial record shows that Lizzie’s bengaline silk exhibited in the courtroom fooled no one—with the possible exception of a confused or biased Phoebe Bowen.

Lincoln contends that the dress Lizzie claimed to have been wearing when the witnesses entered the house in the wake of the homicides, and given to the court, was indeed the dress she had been wearing. The theory, in a nutshell, is that Lizzie changed her dress after the first murder into the uncontaminated bengaline suitable for the street; she intended to leave the house, but Andrew came home unexpectedly early and so she killed him, wearing the bengaline while shielded by Andrew’s Prince Albert coat.

Ms. Lincoln’s theory that Lizzie was actually wearing this bengaline is a major fudge on the trial testimony. Mrs. Churchill provides extensive description of what she saw Lizzie wearing; and most importantly, she is positive that the dress on exhibit in court was not it. Unsurprisingly, Lincoln avoids Churchill’s testimony, since to bring it to light would only discredit the author’s theory. Even Officer Doherty, who was quickly on the murder scene, answers, “No, I don’t think so” [T599] when asked if Lizzie was wearing the dress shown in court. What Lizzie was wearing at that all-important point in time, particularly according to Churchill, was very much like the description of the Bedford Cord as given by Emma and dressmaker Mrs. Raymond; whether it was the Bedford Cord is arguable. But Lincoln’s contention that Lizzie was indeed wearing the bengaline silk she claimed to have worn is patently false if we are to respect explicit statements from credible witnesses. My article, “Victoria Lincoln, Undressed: Exposing a Fiction,” in the October 2004 edition of The Hatchet explores this material in detail and identifies pertinent testimonies.

Lincoln assures the reader that her conclusions are based on a respect for the trial record. Her disregard of the evidence in formulating her dress theory does not bear out this assertion. In short, Victoria Lincoln’s theory of how Lizzie got away with it leaves much to be desired—even if Lizzie did indeed get away with it. So what is the value of A Private Disgrace? If it is not the truth, yet worthy of recommendation—what is it: a murder mystery, compelling and satisfying—one that delivers the macabre goods, and perhaps the most personal, intimately detailed version of the story a la legend.

Ms. Lincoln, a Fall River native whose childhood was spent near Lisbeth of Maplecroft [sic], offers us memories of the real Lizzie Borden. Though they are from an unacquainted observer, they form some striking images. Lincoln’s description of the “Lizzie Borden eyes” is the most thorough one available:

The eyes themselves were huge and protruding, the irises an almost colorless ice-blue. They were strangely expressionless. I have heard many speak of them as dead eyes, but the eyes of the dead are dull; Lizzie’s had the shine of beach pebbles newly bared by the outgoing tide.

The author describes Lizzie’s appearance as “tall, stocky, jowly, dressy, and unremarkable.” She remembers Lizzie filling her bird feeders and having a remote demeanor. She often saw her in her black automobile “that looked like a stray from a funeral procession, sitting alone and staring straight before her.” But Victoria Lincoln’s claim to knowledge goes further than these snapshot remembrances. She professes an insider’s understanding of the Borden family, knowledge of important witnesses, lawyers, judges, and other key players in the trial. This attitude permeates the overall tone of the book:

My parents, of course, knew Lizzie and her circle. Lizzie’s own parents, strictly speaking, had no friends, except for Abby’s half sister and Andrew’s brother-in-law by his first marriage, but my grandfather sat with Andrew on many of the same mill boards and they were both presidents of local banks, a circumstance that has enabled me to uncover the precipitating motive of the crime.

The author frequently uses the pronouns, “I” and “we” throughout the narrative: “We had no doubt that she did it.” This familiarity may be a pretension, but it is an effective storytelling tool that endows the author’s voice with some authority.

At times, Lincoln reads like an on-the-scene reporter—especially during the trial section. And it must be said that the author demonstrates a novelist’s finesse in the trial coverage. More than one author has merely transcribed from the trial record for many boring pages. Lincoln actually transforms this material into an interesting reading experience.

A Private Disgrace does not bore. If the reader is naive about the case or if the scholar can suspend disbelief, then the book is something of a bewitching tale. Convinced of Lizzie’s guilt, Lincoln articulates the objective of her book in the second paragraph of the first chapter:

The case has always held its honest students spellbound, because the factual evidence of her sole opportunity and her guilt is so overwhelming, yet the bare idea of her guilt is so humanly incredible, so absurd. Ever since she was acquitted, Lizzie the legend, Lizzie the case, has fascinated writers; she has to be made plausible.

In other words, by the known evidence, Lizzie must be guilty—but how can an apparently conventional Victorian spinster do such a thing and get away with it? There is practically no question of the mystery she does not answer. Ms. Lincoln believes that Lizzie suffered from a form of epilepsy that adversely affected awareness and self-control. During such an attack she murdered Abby, while also motivated by Mr. Borden’s gift of real estate to Abby. Subsequently, Lizzie’s murder of Andrew was to prevent his knowing that she had killed Abby. The step-by-step particulars of everything Lizzie did on August 4th and afterwards, until she was arrested, are morbidly fascinating. The author knows how to create suspense, her story constantly moves. For example, there is a juncture where she interjects in such a way as to make it practically impossible to stop reading:

Do not be tempted to leap ahead and ask, ‘How did she hide a bloodstained housedress for three days?’ This is a good question in its right place. But not here.

Ms. Lincoln’s extraordinary scrutiny reveals the following:

•Why Lizzie had a hat to place on the dining room table.

•The origin of the “chip” Lizzie claimed to pick up off the floor.

•How the pin-drop of blood happened to be on her underskirt.

•Why the blouse part of Lizzie’s dress was pulled loose, as observed by a witness.

•Why Lizzie mentioned addressing envelopes for Abby.

•Why Lizzie insisted that she barely saw Bridget murder morning.

•The successful concealment of a bloody Bedford Cord.

•What went on between Lizzie and Dr. Bowen murder morning.

And this is not a complete list of Lincoln’s exercise in creative detective work.

About the note that Lizzie claimed Abby received murder morning: the author believes it existed, that it was delivered at Andrew’s behest, and that it was an instruction for Abby to get ready for a carriage that would take her to the bank in order for Andrew to put the Swansea farm in Abby’s name. This note was intercepted by Lizzie and triggered the first murder. But the plausibility of this is weak, as it always is when any author makes an issue of a secret meeting that somehow goes awry. In the case of Lincoln, we have for our consideration the added claim that Lincoln’s grandfather had knowledge of this plot about a property transfer. But realistically speaking, using a moderate dose of common sense—Why should putting the Swansea farm in Abby’s name have necessitated danger or intrigue? If Abby’s presence at the bank were required for the deed to the property—if she were in fact too fat to walk to the bank—why wouldn’t Andrew simply hire a carriage to take them both to the bank? Why not go at the same time as a couple? This logistically simpler method of transportation would have eliminated the circumstances that triggered Abby’s murder, according to Lincoln’s story. Lincoln seems to believe that Andrew, Abby, and John Morse were all afraid of what Lizzie might do as she sat up in her room watching like a paranoid hawk. If Lincoln is to be believed, it would appear that Andrew was overly, tragically elaborate in planning Abby’s trip downtown.

Ms. Lincoln’s treatment of John Morse is sublimely ludicrous. She surmises that he returned to the external premises of 92 Second Street and overhead Lizzie murder Abby. The author reasons the following: “What would you have done in John Morse’s place? I know what I should have done.”

At which point, I should have turned and walked quietly to the next corner, and made tracks for Weybosset Street, there to build up the most detailed and perfect alibi possible. Which, as we will see, is just what John Morse did.

I would rather believe that Ms. Lincoln is blinded by the melodramatic possibilities of fiction when she states what she would have done under such circumstances. Because in fact the thing to have done would have been to direct Bridget away from the house to fetch Dr. Bowen and the police, and last but not least—to have prevented Andrew Borden from ever even entering the house. I draw attention to this part of Lincoln’s story to show a complete breakdown of plausibility. Consider the implications—that Morse could have caught the murderess red-handed and prevented the murder of Andrew. Of course, we don’t know the moral character of Morse, but the point is that Lincoln herself forgets the moral reality we may fairly call human decency when she identifies with a decision to flee from Abby’s murder in search of an alibi.

Unlike other authors, Victoria Lincoln believes that in some real sense she does know Lizzie Borden:

I mean that Lizzie and I grew up in the same provincial mill town, that we belonged to the same stratum of its highly stratified society and were both creatures of an era that ended just as I reached my dancing days on the far side of World War One—the watershed.

According to Lincoln, Lizzie’s character and guilt were more or less known among a certain class of Fall Riverites. She had “peculiar spells” and was “given to obsessive, self-righteous brooding.” One of the most interesting parts of the book is the author’s analysis of Lizzie’s inquest testimony, from which she distills some interesting psychological traits:

It is strange to study the mind of one who is at once so unimaginative and so wholly out of touch with reality. Yet though she plods and cannot invent, she is never really unintelligent, except when it comes to people. In fact she is often shrewd. But out of touch—just out of touch.

Lincoln’s Lizzie is dull, average, and pretentious. But above all—limited. The author uses an interesting phrase, “mechanical emptiness,” to describe the latter part of Lizzie Borden’s life. A life limited in scope, range, and human contact—this is the climax of the guilty and pathetic existence of Lizzie Andrew Borden. And the last sentence of Ms. Lincoln’s book, a morbidly sentimental observation, is truly inspired—an image especially for the visitors of Oak Grove Cemetery to ponder.